The jukebox musical isn’t so named merely for its carousel of beloved pop tunes. It also puts to shame good storytelling for a few bucks and a song.

I must confess that sometimes I feel silly walking into jukebox musicals like Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of The Temptations with a notepad and pen, a little out of place among audiences who (rightfully so, more power to them) fawn over the painfully corny, brainless writing, who scream and squeal at the barely believable recreations of childhood idols before them — lambs at the altar of manufactured nostalgia. Someone in the front row stretched their hand up to the stage during a lively number — “Get Ready (Cause Here I Come),” probably — gushing that they might, finally, touch the hand of a real Temptation (there is, after all, a silver lining in such a dreamy gesture, but we’ll get there). Another person behind me kept yelling “Awesome! Awesome!” every time a song started and “Feel the hurt! Feel the hurt!” whenever something mildly sad occurred. It’s as heartening to see audiences so wonderfully engaged as it is hard to take anything seriously sitting before a musical that shrugs off even the slightest critical concern for the making of good theater, choosing, instead, to spoon-feed grateful audiences a tasteless confection of unearned sentimentality.

It’s escapism and commercial Broadway entertainment at its finest (and most calculated). All of this should come as no surprise, of course; every year we sit through more of them. Last year it was Donna Summer; this year it was Cher and The Temptations; next year it’ll be Tina Turner, and I suppose we owe the sorry lot a debt of gratitude. For better or worse they keep the seats filled. Yet, somehow, this time it hurts even more.

The Temptations and Motown Records staged an extraordinary cultural experiment that forever changed the fabric of American popular music, that saw the impossibilities of the American Dream and built a new ladder, one working-class black kids could climb to find everlasting success — that’s how the popular myth goes, at least. Berry Gordy, through genius and hard work, conned the racial fantasies of white America to build one of the largest music empires in this country’s history. It’s a parable that lays bare the racial realities of the American musical imagination — that unmasks the creative genius of selling records to a white America who got off at the sound of black music at a comfortable distance, that divulges the dangerous and radical work of putting five black men on American Bandstand and that chronicles the need to construct a label for black artists, music and audiences during a time when mainstream American pop culture was well at work in turning the blues and rock n’ roll white. The story of Motown and The Temptations is also the story of a vibrant American proclivity for making myths of this sort, for reading into The Temptations and Motown Records some triumph of solving race in America or imbuing in Berry Gordy a cultural ingenuity beyond the good, money-making sense of selling pop music to an audience he understood well.

There are greater sins at work in a musical that buries this story, however, you tell it, under commercial jukebox kitsch. But, before we get to those, a necessary laundry list of creative turpentine:

Prolific playwright Dominique Morisseau, who’s recently won acclaim for her extraordinary three-play cycle The Detroit Project, was tapped by Ain’t Too Proud’s producers and seasoned jukebox director Des McAnuff to adapt Otis Williams’ memoir (the Temptation is also an executive producer) into a book musical. While I, and we all should, appreciate that writing from a woman of color is featured on Broadway, no playwright, however well-fitting their particular style and corpus might be, can escape the vortex of jukebox doom. There simply is no way to embody the complexities of an entire career, especially with a group like The Temptations, on its shoulders not only the enormous cultural weight of Motown but the personal stories of over twenty members who’ve come and gone, into a cohesive and linear musical, subservient to the narrative inclusion of thirty one — yes, thirty one — hit numbers. By the time the second act wraps up, the musical having dizzyingly bounced from the dark personal lives of each of its founding members — Otis Williams (Derrick Baskin), Paul Williams (James Harkness), Melvin Franklin (Jawan M. Jackson), Eddie Kendricks (Jeremy Pope) and David Ruffin (Ephraim Sykes) — from every major city on the planet and up and down the Billboard Hot 100s, the play must so frantically kill off enough Temptations to reach the story’s end that Otis Williams literally starts wheeling them off the stage (Eddie Kendricks spends about a minute in a wheelchair, from which we’re supposed to gather he’s fallen ill and died, and quickly whisked away).

To contain it all the musical can rest only on insufferable cliches to tell its story. Perhaps no other moment is more emblematic than Otis Williams’ touching (cough, cough) moment with the audience, after having narrated the tragic death of his teenage son in a several minute scene underscored by “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” (yes, his papa was a rolling stone, too). Standing wistfully at the proscenium, he reminds the audience in a penultimate thematic moment: “The only thing that lives on…” — pausing, as the entire audience audibly whispers “the music..the music..the music..” — “…is the music!” Uproarious applause.

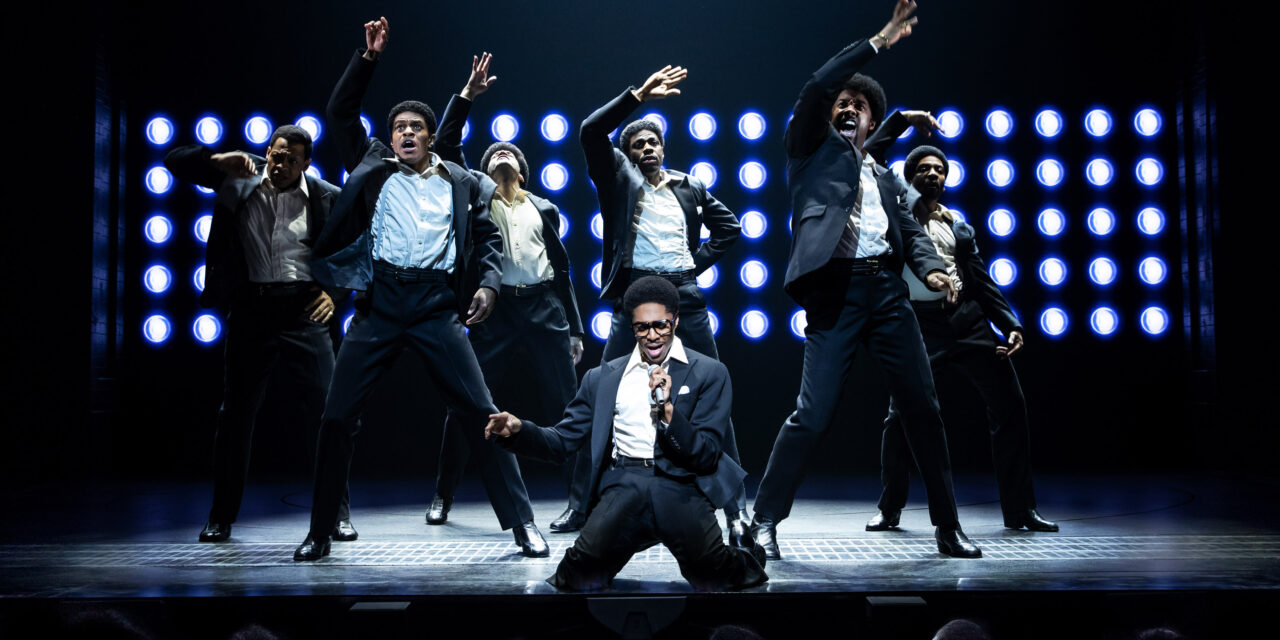

Ephraim Sykes, Jeremy Pope, Derrick Baskin (center), Jawan M. Jackson and James Harkness in “Ain’t Too Proud.” Courtesy of Matthew Murphy.

How those thematic elements transfer into staging and scenery is often more laughably entertaining. Like the Donna Sumer jukebox, Ain’t Too Proud has relied on a set of moving screens and projections (Peter Nigrini) to ground the light-speed narrative in time and place. Most scenes exist on an entirely black, empty stage (scenic design by Robert Brill) — the colors in this musical are surprisingly cold and stark — while a screen displays a city name like “Detroit,” some flames on newspaper headlines to signify a race riot or raindrops over a picture of Martin Luther King Jr.’s face to show sadness. The narrative moves so fast, most scenes either incredibly short or existing in some nebulous, ambiguous space (my favorite is the rotating dance number with screens flashing different city names to signify “touring”), that set pieces are largely out of the question. The crutch, then, becomes some tired stage gimmick. In Donna Summer, it was the pedestal; every time someone dramatically entered or exited the stage, she sunk down or rose up on this little box which popped up and down like a rectangular gofer. In Ain’t Too Proud it’s a set of treadmill-like runners, which literally ferry people on and off the stage at lightning speed; they allow all five Temptations to rush centerstage in mere seconds or, in the case of someone’s death, to take a slow, funereal ride to the wings.

The other tragedy is seeing true Broadway stars like Jeremy Pope or Ephraim Sykes in a musical like this one. Leaving his acclaimed run in Choir Boy to join Ain’t Too Proud, Jeremy Pope musters as much might as possible to bring true dimension to his character of Eddie Kendricks. I do fear his delicate tenor, which brought the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre to tears in Choir Boy, is buried under the lumbering, often over-powering orchestrations in Ain’t Too Proud. It’s particularly painful to see the up-and-coming Broadway star, whose performance in Choir Boy excavated depths of queerness and blackness in American life never seen on Broadway, confined to a musical which so clearly skirts the same difficult conversations in this show.

Nevertheless, there is some hope here. I did feel for whoever reached out of their seat to touch the garment of The Temptation (I believe it was Ephraim Sykes as David Ruffin, who is truly the most impressive, electrifying member of this cast). There is something serious to be said about the power of representation in musicals like this one, in the ability to erect these monuments of black identity on a stage as powerful as Broadway’s, to put idols of this sort onstage for old fans and young kids alike to witness in celebration. There are, for sure, countless fans making the pilgrimage to Broadway to see Ain’t Too Proud, Americans who once bought these records and never thought they’d see five, powerful black men celebrated as these Temptations are. As the title suggests, the theme cultivated throughout the show is one of humility, of working together to make something great and to rise above vitriolic hate — and there’s nothing bad about that.

But it is genuinely disheartening to see Ain’t Too Proud corner itself into the same, purposeful paradigm The Temptations themselves were forced to occupy. The great parable of this group’s rise to fame was what they sacrificed in becoming a Motown “cross-over” — black enough to appeal to the tastes of white America re-consuming black history and music at the rate of about one decade every year, but not too black, not too obviously and threateningly sexual to scare the racist, exoticist tastes of their white audience.

In many ways, race exists in Ain’t Too Proud in similar proportions, more often offered as a melancholy set up to a sentimental song, simplified, brushed-over or paired with a disarming joke to diffuse an audience uncomfortable confronting the ugly face of racism in America, or hearing Jeremy Pope use the n-word, during their night out at the jukebox.

Here’s a telling scene: the team is touring the South, collected in their tour bus. Someone mentions the real danger of traveling through the American South as five black men in a bus. White Americans love their music, but certainly not them. Shots are fired. The Temptations drop under their seats. Off-stage, several voices howl racial slurs, not to face the audience. To come out from the wings might make too painful a reflection.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.