Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

In the last ten years since the death of Pina Bausch, Tanztheater Wuppertal, the company she founded in 1973 in the remote German town of Wuppertal, has continued to exist as a means of protecting her legacy. New dancers have been admitted into the company and trained up to be able to perform the existing repertoire, but there have been no new additions to the programme until a few months ago when Greek director Dimitris Papaioannou and Norwegian Alan Lucien Øyen were invited to create new work at Tanztheater Wuppertal. These two works are currently on tour in London’s Sadler’s Wells.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

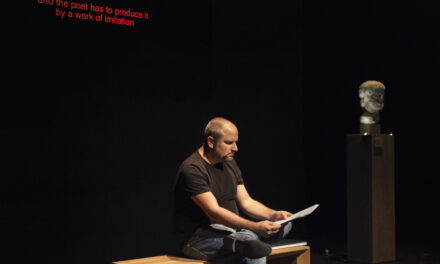

New Piece I: Since She is framed as a tribute to Pina, by the 54-year old Greek visual artists and theatre-maker Papaioannou, who owes one of his most profound and formative theatre experiences to seeing Bausch’s Café Muller in Athens at the age of 19. Since then he had gone on to create artistically distinctive works himself, including most notably the opening and closing ceremonies of the Greek Olympics in Athens 2004.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

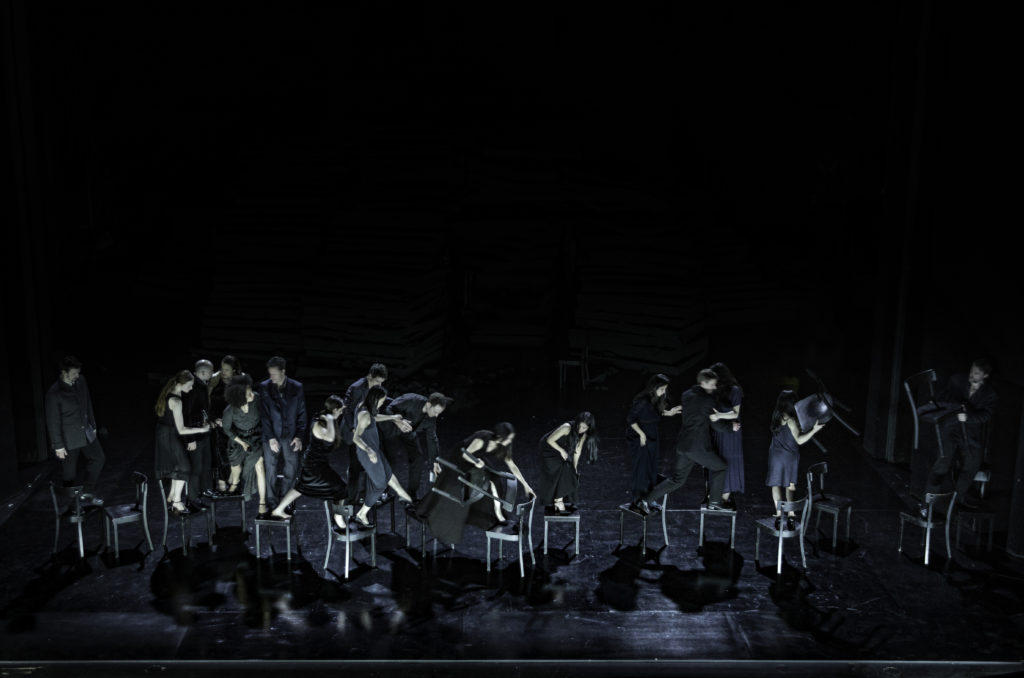

Rather than virtuosic dancing and choreography per se, Papaioannou’s work is characterized by an interest in striking imagery, optical illusion, and strange formations: one torso, one skirt, and several pairs of legs in a single dancing number; a woman dragged on the floor by a man while a set of glasses filled with water glide after her balanced on the strands of her hair sprawling on the floor after her. Perhaps this represents an appropriate stepping stone for the company, and a leveler for the old and new members forced to learn an entirely new stage language.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

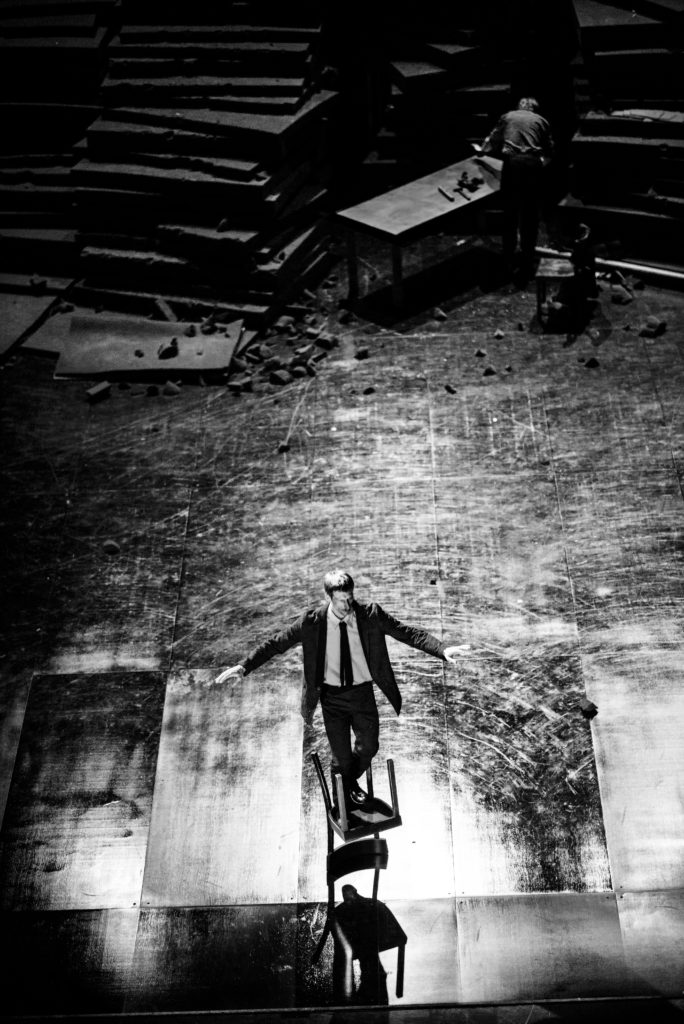

Beyond featuring some visual referencing of Bausch for the first few opening minutes of the show–the evening dresses, the chairs–New Piece I mostly resists any coherent or consensual interpretation. It is more like an elaborate dream than a discernible thematic entity of any kind. Tina Tzoka’s set design consists of a mountain-like dark grey staircase structure made of thick foam. Dancers climb, emerge out of, disappear into it, and on more than one occasion, nosedive at snail speed down this structure. The tone of the entire 90 minutes is predominantly slow and meditative, the movement ranges between standing still, imperceptible motion, hobbling, scuttling, sliding, and sashaying. There is only one brief moment of highly stylised Greek line dancing in the show as a whole. Not infrequently the dancers engage in seemingly impossible circus-like feats–balancing on an upturned chair, sledding down the staircase in an upturned table, building a structure of multiple chairs on top of one’s shoulders.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

There are elements of Greekness in this show–clear references to Greek mythology, both ancient and modern (a lamb on a skewer, anyone?)–and within the context of this show being made in Germany, it is impossible not to wonder whether the makers might not have considered the recent political history of their respective countries in relation to each other. I am referring to the Greek economic crisis of 2015 and the way in which the Eurozone, led by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, was largely perceived as unsympathetic to Greece at the time. Though it might seem too far-fetched to claim any political content in a show as decidedly enchanting–and evidently enchanted by loftier considerations of love and beauty–this residue of the underlying clash of the respective cultural mindsets, and the impasse in mutual understanding, might have quietly continued to inform, if nothing else, than at least my own individual reading of Wuppertal’s New Piece.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

As far as the running themes go, there is a persistent element of real labor taking place in this show–this is artistic labor, but dedicated, applied, serious labor nevertheless. It, therefore, seems inevitable to consider the notions of art and craft in relation to this theme of labor, as well as of course, economy, surplus and deficit, and ultimately reward too.

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

The show is framed by two very simple images: 1. A man, alone, balancing, for real, and for an impossibly long and sustained period of time, on a precariously perched chair. 2. Some 90 minutes later (in the aftermath of a short romantic interlude in which sparks are shown to be flying), the same man balances on the same chair in exactly the same way, only this time, the image is completed by the body of the woman nestled into it, providing stability and ballast. Perhaps that is the point of the show–that in the matters of hard work, the thing that makes it worthwhile is some sort of collaboration, counterbalance, harmony, or love?

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, New Piece I: Since She Photo credit: Julian Mommert

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.