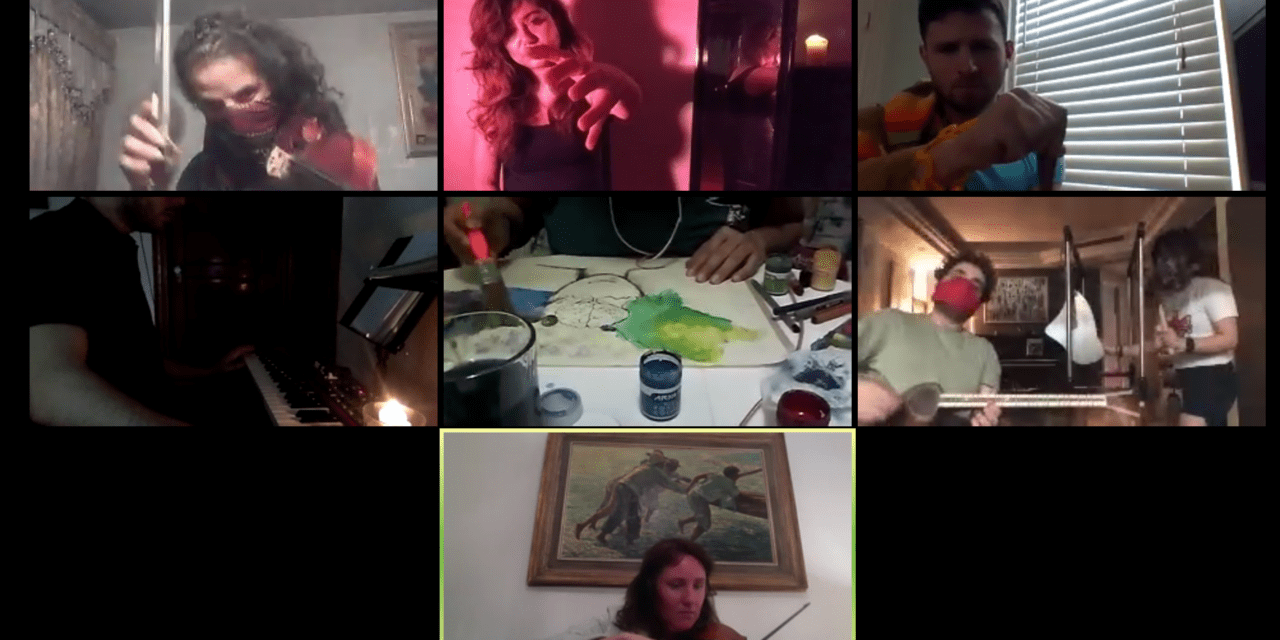

M(O)ther is an international online collaboration to be shown August 9, 2020: 2pm EST, 8pm South Africa, 9pm Iraq and Turkey, 10:30pm Iran. It will feature original music, modern poetries (Farsi, Arabic, Turkish, English), live drawings, and physical performances. Heather Waters, dramaturg for the production, interviewed Vahdat Yeganeh, the Founder and Artistic Director of Boston Experimental Theatre, about the upcoming show.

Heather Waters (HW): M(O)ther is the fifth Dialogue among Civilizations theatre production you have directed and produced at Boston Experimental Theatre. How did you come up with the project idea?

Vahdat Yeganeh (VY): The first time I heard about Dialogue Among Civilizations was when Mohammad Khatami, the former president of Iran, spoke about it at the United Nations in 1998, and that is how I became aware of Daryush Shayegan and started reading his books. Two years later, I started working at Iran’s Center of Dialogue Among Civilizations in its newly formed theatre department.

(HW): What was the Center’s theatre program like?

(VY): There were three of us that started the theatre: two men and one woman. As I was the youngest of the three, I assisted the other two. Our first task was to invite and organize a board to make goals for the department. We brought together seven well known Iranian theatre artists. What was unique was that none of them had worked for an institution or taught at a university for a long time due to government regulations. Among the seven were scholars, directors, actors, and designers. While working on getting the board together, we focused on three missions: 1. to create opportunities for young students to direct and perform productions related to the Dialogue Among Civilizations; 2. translate and publish scholarly books that were necessary for theatre artists to read– our first goal was to work with Peter Brook’s masterpiece The Empty Space, and 3. invite international artists to come to Iran for workshops and seminars. The Dialogue Among Civilizations program at the time had to go through many hardships. Fundamentalists in Iran were against the idea of starting a dialogue or a relationship with the West of any kind and against the existence of the Reformers’ Party in Iran. Sadly, by the end of Summer 2000, after performing a number of students’ projects, but before being able to meet any other tasks, we were told that the budget for the theatre department got cut. We couldn’t work there anymore.

(HW): What did you do next in theatre?

(VY): The year 2000 was a big year for me. At the age of 21, I worked for Dialogue Among Civilizations, published a theatre article in a national newspaper (Bahar), and I directed my first professional play in Tehran’s Theatre City Hall (The Most Honest Murderer in the World-an experimental play that was performed in the coffeeshop). During that time, the Reformer Party was in control of the government and the parliament. Everyone could produce theatres, many books were published, we had more newspapers and magazines than we ever seen in Iran. We had more concerts than ever.

(HW): The year 2000 was the year President Khatami’s Dialogue of Civilization initiative sparked a lot of enthusiasm in the United Nations to the point that Year 2001 became known officially at the U.N. as the Year of Dialogue Among Civilizations. Then, of course, the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York changed everything.

(VY): Yes, progress for the initiative was being made internationally, but in Iran, the right-wing parties and Islamic fundamentalists were at war with the President and everyone who supported him. Many scholars and students got jailed and also killed. While the government would help theatre artists to produce productions, fundamentalists would attack the productions and force theatres to cancel the shows. While the government would give licenses to journalists to publish in newspapers, fundamentalists would attack their offices, cancel their licenses, and bring them to ‘a theatrical court’ to sentence them to prison. These are just a few examples of the danger at that time.

Although I was young and unknown, I got affected too, and I never knew why! My first production in Tehran as a director got banned before the run was over; soon I was called to go for a hearing. The hearing worked like an interrogation. Accusations against me were based on my parents’ religion being Bahai, and my underground involvement with the Bahai community through teaching and organizing theatre events. The theatre articles I had published in Bahar (also eventually banned as a Reformers’ Party supporter) also became suspect. I was accused of hiding symbolisms against the regime in Iran in my theatre production. Most important of all, I was told that I could not continue doing theatre anymore because I was born in a Bahai family. When I left that meeting/interrogation, I was scared, and I felt the fear of death in my bones thinking that I may not ever be able to do theatre again. A few weeks later, I found a smuggler to take me to Turkey through a 10-hour walk in the mountains. I went to the U.N. office in the city of Van and requested refugee asylum.

In response to the 9/11 attacks, President Khatami and many Iranian people showed their solidarity with the victims of the 9/11 right away and spoke against any acts of terrorism. Yet, just five months later, U.S. President George W. Bush called Iran a part of an Axis of Evil in his State of the Union address, although there was never any evidence showing Iran had a part in the attack. His comments weakened the Reformer Party that was trying to open doors to more with the West. Unfortunately, with the current administration, we see the same pattern repeating itself.

(HW): How did this experience lead you to Artaud and Grotowski? Or did it?

(VY): At the time I was already introduced to Artaud and Grotowski, although there was not much information about these two in Iran. From the few articles I read about Artaud and Grotowski, I knew there was something personal in their theatre that I loved deeply. I am strongly inspired by Artaud’s concept of the Theatre of Cruelty. I personally call it the Theatre of Psychic, meaning this theatre is not about how life is, or how it should be, but how it is in our deepest dreams and unconscious. Grotowski was looking to create interpersonal relationships between his actors and audiences. He described his theatre as a laboratory–both actors and spectators were forced to take off their social masks to confront each other with deep feelings they had hidden inside. To me, this was an ultimate form of dialogue, not just through information and language, but an internal communication to share one’s deep feelings and dreams with others. That has been a major focus of my study and work in the past 20 years. I personally find it the most amazing way for artists, producers, and spectators to have a cultural exchange in theatre, where our differences in language, music, politic, and religions are stripped away, and we practice to connect to one another in a deep psychological way–through our dreams, anxieties, fear, and love. This practice has been the focus in our production of M(O)ther.

Photo Credit: Emily Wright.

(HW): It is exciting, due to long term hostilities between our governments, that actors and musicians from Iran, Iraq, and the United States are collaborating and will appear together in M(O)ther alongside artists from Turkey and South Africa. How did you get to know the cast members?

(VY): It all started when I met Ameen at an online concert during the pandemic. It was the first time I was seeing an Iraqi artist. After many years of war between Iran and Iraq, it felt surreal to see an Iraqi artist. Right away I found him online and messaged him. Less than 12 hours we spoke on the phone. I told him I never worked with any Iraqi artists, and he told me he never worked with any Iranian artists, and we did not know of any Iranian and Iraqi artists that worked together. We both were surprised and did not know why this was so! In the same phone call, we decided to do a project together that had to be online because of our locations. I spoke to B.E.T.C. members (Jared, Donya, Emily, and Engin) and everyone was excited and agreed to join.

B.E.T.C. has worked with Brenna, Elinor, and Leva before, and we all wanted to do another project together. I also know Peyman and Astiaj for three years, and we were always looking for an opportunity to work together, which proved very difficult because they are in Tehran and I am in Boston. This online project was a great opportunity to collaborate with everyone in spite of travel restrictions and with everybody on Zoom due to the pandemic quarantine. At the same time, you and I started brainstorming to work together on some online educational programs that would expand a Dialogue Among Civilizations program to students from around the U.S. and world. We decided to pause that project and focus on this first.

(HW): There have been several discussions in rehearsals about the Black Lives Matter movement and its impact on the play. To prepare for my dramaturg role, I read Shayegan’s book translated into English, Cultural Schizophrenia. I was struck by how he went internal regarding obstructions to open dialogue between the East and West, focusing on Iran’s deep social problems, versus the deep problems of the U.S. that prevent constructive dialogue. How do you see working in the U.S. at this juncture?

(VY): In the past three years in the U.S., we have seen how fear of the other has been exploited and endorsed by the current administration, but this is a historical problem. Here in the U.S. “others” are to be scared of…other colors, other religions, other languages, other thoughts. This kind of racism and division is what I experienced growing up in Iran being Bahai born, and I have experienced it in the past 18 years living in the U.S. as an immigrant coming from the Middle East.

The idea of appropriating Dialogue Among Civilizations started for me in 2013, when, as an Iranian born and U.S. citizen who loves both countries deeply, I feared war between the two countries more than ever. I felt and continue to feel the responsibility to use my theatre, no matter how cruel and abstract, to create an environment for Iranian and American artists and audiences to have a collective experience through theatre and the performing arts.

In M(O)ther, our collaborators get closer to each other in every rehearsal by sharing their pains, their broken dreams, their fear of their homes. The ability to share our pains and dreams through our own languages and music is what make us the happiest at the end of each rehearsal. We hope that through this production, our audiences personally and deeply experience the connection produced among these artists.

(HW): How did you arrive at the Mother-Other theme of M(O)ther?

(VY): We are from different countries and cities, rehearsing online in our private boxes, in different time zones, getting to know each other through different languages, translations, different music, and drawings, all behind our computer’s glass. No one could touch or be touched physically. We collectively feel the pain of being in other places and share the desire to get closer to each other. We talk about our countries (motherland), our languages (mother tongue), our environment (mother nature), our music (lullaby). Keeping mother as core to the theme helps us create many images, fantasy and interestingly connects us all together unconsciously and consciously. That is why I chose M(O)ther as the title. This format of the spelling of mother has been used before in modern psychoanalysis for very different reasons, but I thought it fits very well with our production playing around the themes of mother and other at once.

Here is a link to watch the performance on August 9: M(O)ther.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Heather Waters.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.