Kyoto Experiment is one of Japan’s major international theatre festivals, along with Festival/Tokyo and the Shizuoka International Theatre Festival. Showcasing works that transgress the borders of artistic genres, Kyoto Experiment has contributed greatly to establishing Kyoto as a platform for innovative developments in the field of performing arts.

The Theatre Times had the privilege to interview Kyoto Experiment program director Yusuke Hashimoto who told us about the core concepts of the festival, as well as about how this project started, the challenges they faced and how the festival reached the scale it has at present. We also received insights on the program and highlights of Kyoto Experiment’s 9th edition which will be held from October 6th through the 28th, 2018.

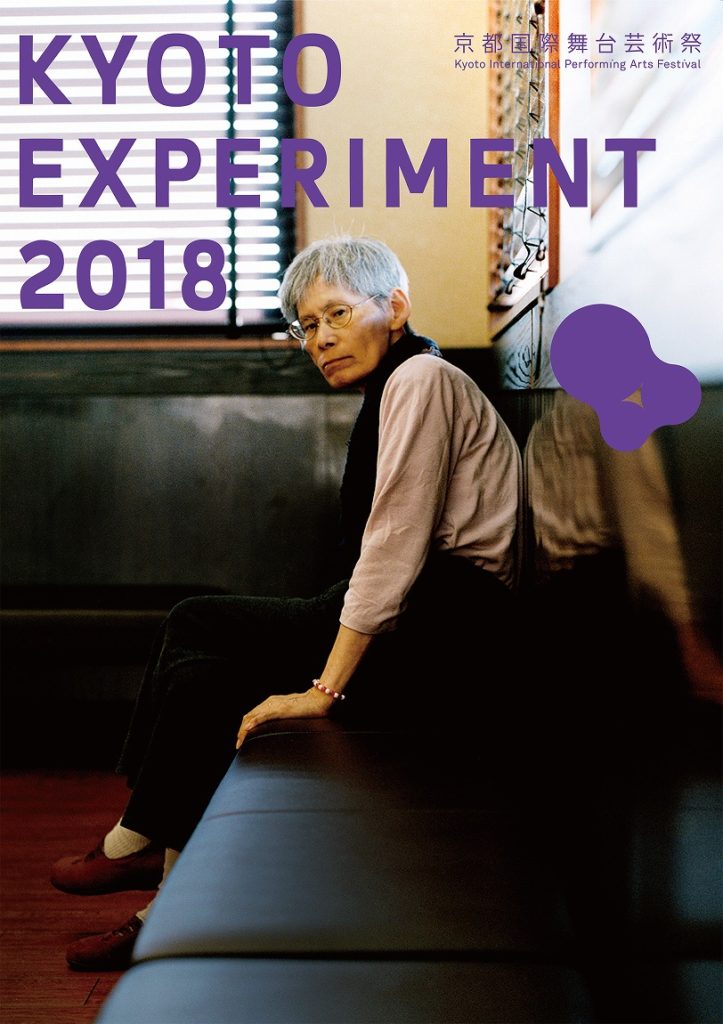

Yusuke Hashimoto

ROHM Theatre Kyoto/Kyoto Experiment Program Director

Born in 1976 in Fukuoka. After establishing the Hashimoto Performing Arts Production Office in 2003, he has been active as a producer of contemporary theatre and dance performances. After founding Kyoto Experiment, Kyoto’s first international performing arts festival, in 2010, he has been the program director of the festival ever since. Since 2013, he has been the director of the Open Network for Performing Arts Management (ON-PAM). Since January 2014, he has been the program director of ROHM Theatre Kyoto.

RT: Could you tell us how Kyoto Experiment started? What was the incentive of this festival?

Yusuke Hashimoto: We had the first edition of the festival in 2010. Kyoto Experiment was launched as Kyoto’s first international performing arts festival. Before 2010, from 2002 I had been working as an independent theatre producer in Kyoto. At Kyoto Art Center, located in a former elementary school building, I used to work with young artists from all around Japan in the frame of a program called Engeki Keikaku (“Theatre Project”). They were able to use a studio inside the Arts Center free of charge. We used to produce one or two stage works every year.

Some very good works were born there actually. For example, the play Isn’t Anyone Alive?, written and directed by Shiro Maeda (*1), was performed there for the first time. He was awarded the Kishida Kunio Drama Award for this work.

Or the work titled It is written there by Kyoto-based choreographer Zan Yamashita, which was invited the following year (2008) to feature in the Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels. Performances that were subsequently invited to join Festival/Tokyo have also been created there.

However, although we kept releasing good works, there was no increase in the number of people coming to watch them in Kyoto. In fact, the theatre journalists and professionals based in Tokyo would not come to Kyoto, so it was really problematic. In order for their work to be recognized, the artists were constrained to go to Tokyo. That had become the rule of thumb.

Theatre works have, or supposedly have, a certain connection with the place where they are created. So it would have been best for everyone to come and watch those performances in Kyoto. The artists who chose to work in Kyoto should have been encouraged to do so. But, no, the artists residing in any other areas outside of the capital were constrained to go and perform in Tokyo. I wanted to change that.

Somebody suggested that if it were possible to watch two or three performances in a day, theatre professionals would come to Kyoto. That was what inspired us to start a festival.

There are many young artists who choose Kyoto as their base. We wanted to create a good environment for them to continue creating in the city that inspired them.

In addition to this, there was one more reason, actually. Japan is not a very large country, but still, each region has a slightly different culture and its own characteristics. And Tokyo is in no way representative of all of those cultures.

In promoting Kyoto, the government uses images of geisha, kimonos, traditional Japanese dances, etc. However, those images have very little in common with what we, the citizens of Kyoto, experience every day living here. Instead of having Kyoto’s cultural identity decided by someone from the outside, we would like to decide for ourselves the features of our cultural identity.

Kyoto may seem a traditional city but, in fact, it is home to several universities and research centers involved in the development of advanced technologies. However, those who are aware of this particular feature of Kyoto are very few.

RT: Was your intention to make it an international festival right from the beginning?

Hashimoto: Yes, right from the start we wanted it to be an international festival. Of course, we wanted the festival to feature Kyoto-based artists. As for the artists from abroad, we decided to invite mainly artists who have an explicit visual dimension to their work, who employ methods that are specific to visual arts. We suspected that Kyoto audiences may not be so fond of theatre that’s centered on words, on talking a lot, so we thought we might as well try to attract audiences who have an interest in the visual arts. And I think we actually succeeded with this concept. Because we wanted to attract audiences with broad interests, we aimed to create a program that would be appealing for people who enjoy visual arts, music or dance as well, not only theatre.

RT: What was the program of the first edition like?

Hashimoto: The 2010 edition featured, for example, Masataka Matsuda (*2), who was based in Kyoto then. He presented a new creation and separately he wrote an original Noh play for another performance. We also had a performance by the theatre company Chiten (*3), who is still active mainly in Kyoto. From the international scene we had Gisèle Vienne, who was an artist in residence at Villa Kujoyama in Kyoto. In collaboration with Shiro Takatani and other artists, she had created the work This Is How You Will Disappear. We also invited Pichet Klunchun from Thailand who was working on a piece themed on traditional art in the contemporary society titled About Khon. Work on this performance had been started in Thailand, but once brought here, Kyoto provided good material and inspiration for it. The program also featured Akira Takayama (*4), who had just started his series of site-specific works with real cities as their stage.

More recently, the autumn festival in 2016 also featured many artists whose interests go beyond the theatre, into the field of visual arts – in a word, multimedia artists. Some of them would hold a performance in one location and an exhibition in another. For example, Ryoji Ikeda (*5), who participated with a site-specific installation and a stage concert. Or Michikazu Matsune, who is active now in Vienna. He is best known as a performing artist, but that year he was also in charge of the curation of an exhibition in Kyoto.

On the other hand, in 2017, there were many works related to music. For example, Ryoji Ikeda’s direction of a percussion ensemble. Or a music theatre performance by Heiner Goebbels & Ensemble Modern.

In other words, we don’t want to limit ourselves to theatre and dance. Any type of performance presented on a stage can be considered for the program.

RT: Last year, the theme of the festival was “Otherness.” What made you decide upon this theme?

Hashimoto: It was actually the theme that came up first. Kyoto was hosting a series of events on intercultural communication and Kyoto Experiment was asked to participate by inviting artists from Asian countries such as South Korea. Usually, when intercultural events are held through a governmental initiative, participants from various countries are invited to Japan and asked to showcase their own cultures.

However, when it comes to East Asian nations, are we really so different from one another? The peoples in East Asia have so many things in common, not to mention that with the spread of the Internet, we are all connected.

So, if we think about it, in every individual there is some kind of “otherness”, we carry pieces of other individuals’ lives in ourselves. The intercultural exchanges sponsored by the government are based on the idea that the culture of each country has an independent identity. So, the aim of these exchanges is to have a dialogue between the many different cultures. But in reality, there is no such thing as independent identities. We all have mixed identities within ourselves. That was the incentive behind last year’s theme.

Photo: Shingo Kanagawa. Design: UMA / design farm

RT: What about the theme of this year’s edition? What brought you to create a program focusing on the work of female artists?

Hashimoto: Each year we hold a press conference before the festival. A few years ago, I was looking at the pictures from the press conference and it suddenly hit me: most of the members are men. There was something disturbing about that group made almost exclusively of bearded, middle-aged men. It made me think about how patriarchy as a rational system for leading a group, regardless of whether in the arts or not, will unwittingly be imitated. However, unless we question this, there might never be any theater or dance works that manifest collective creativity in a true sense. The status of women in Japan is extremely vulnerable and so I wanted to create this program so the festival can function as a forum for people to think about this problem through the medium of the arts.

.

RT: Could you be more specific about what this vulnerability consists in?

Hashimoto: For example, there are too few women involved in politics. Or the fact that there is a difference in remuneration. For doing the same work, there are cases when women are paid less, even if they have the same level of education. Not only in politics, but also in companies and public institutions, there are too few women in managerial positions. What this means is that the work environment is not appropriate for women. The system and rules concerning work are decided by men, who have no real understanding of what is needed for women in the workplace.

I was talking to a female journalist the other day and she was telling me that when she started working in the media, her first appointment was in the “Lifestyle” section. It wasn’t the “Politics” section. It was considered natural that women should be in charge of “Lifestyle” and not of “Politics”. What this means is that the voices of women in society are underrepresented.

In my work with theatre and dance, I can also feel it actually. Stage works are created by groups of people and when it comes to group management, a patriarchal system is very convenient: you have a “father” figure watching over the group and the ones under him listen to what he says. I’ve seen many performance works created through such a system even though there were also female performers involved. However, in a group there should be various types of people.

At Kyoto Experiment, our aim is to discover new types of expression. In order to do this, I think we always need to doubt the way we are doing things.

In the Japanese society, this topic has been gathering a lot of attention in recent months, but we already had this idea to create a female focused festival program since two years ago.

RT: The artists invited to participate in this year’s edition of Kyoto Experiment – how will they deal with this focus?

Hashimoto: The artists will either be female or artists and groups that identify as female. And by this I don’t mean that these works will be feminist. It will be rather that topics that are usually dealt with from a man’s perspective will be approached from a woman’s perspective.

RT: Can you introduce to us the artists who will participate this year? What features of their work made you decide to invite them?

Hashimoto: This year, we have invited The Wooster Group, a company acclaimed internationally for their innovative use of multimedia in their performance. They will be performing for the second time in Japan. When they came here for the first time, they performed only in Tokyo. At Kyoto Experiment, we are seeking to discover new types of expressions, but we also think it’s important to know what experiments have been done before. That is why each year we invite a “legend.” Last year, for example, we had Trisha Brown Dance Company.

The Wooster Group will present a work, THE TOWN HALL AFFAIR, themed around the second wave of feminism that took place in America around 1969. It’s a performance that fits the profile and intention of this year’s festival perfectly.

François Chaignaud and Cecilia Bengolea will be taking part for the second time in Kyoto Experiment after four years. They both have a background as ballet dancers, but the works they are creating together have an underground edge to them. They deal with views of sexuality that are usually considered taboo, approaching them through an open, often humorous perspective.

Satoko Ichihara / Q, Photo by Mizuki Sato

Satoko Ichihara is a Tokyo-based artist. She will present a work focused on Tokyo, actually. To be more precise, her work focuses on the pressure that the city of Tokyo puts on women. This time, rather than politics, the force behind it all is capitalism. In Tokyo, women are bombarded from all sides with ads suggesting them to stay young, to diet, to remove their body hair, to get loans, etc. Through Ichihara’s perspective, this all becomes a comical and grotesque story. For us who live in Kyoto, it’s very interesting to see how Tokyo is depicted in her work. It’s obviously a place with a different locality. In a way, Tokyo is indeed a strange city, different from any other place in Japan. This becomes clearly visible in Ichihara’s work.

RT: From your point of view, what is the position of Kyoto Experiment in Japan’s contemporary theatre scene?

Hashimoto: Kyoto Experiment is probably better known overseas, especially in the circles of theatre professionals. To start with, we have few international theatre festivals. There are Festival/Tokyo and the Shizuoka World Performing Arts Festival. We also have the Aichi Triennale, but it focuses rather on the visual arts and it’s held once in three years. In the world of contemporary Japanese theatre, we are probably somewhere at the margin. (laughs)

Even if Tokyo is not the heart of the theatre world anymore, the authorities that grant subsidies for cultural activities are still based in Tokyo. There may be many young people, artists or critics who know about Kyoto Experiment, but I don’t think that there are many members of the older generations who know about it.

TTT: Until recently, everyone was talking about the “small theatre movement” when referring to contemporary theatre in Japan. Since the late 80s, it was mainly the activities of companies that were active in small theatres (*6) setting the tone for the new developments in Japanese theatre. What is the position of Kyoto Experiment toward this type of categorization?

Hashimoto: We don’t want to use the term “small theatre”. You only have something “small” if you first have something “large” to compare it to. That means that what happens in the small theatres is something “alternative”.

Even among the young Japanese artists there are some who wish to work on the big stages someday or to do work related to the television. They are probably driven by the need of having their way of thinking confirmed by as many people as possible. I’m not really interested in these artists. For Kyoto Experiment, artists who want to have their vision and works tested, artists who are willing to face the world and the international scene are better suited.

RT: What has changed in comparison to ten years ago in the Japanese theatre scene?

Hashimoto: Well, the gap between commercial theatre and artistic theatre is deeper than ever. Artists who used to be introduced together ten years ago as the new voices of the theatre scene, such as Toshiki Okada (*7) and Daisuke Miura (*8), ended up doing very different things. Okada tried for a brief time to work with the National Theater. It didn’t work out so he decided to focus on his work with his theatre company, chelfitsch. While Miura is now involved mainly in commercial productions. The artists have to decide now whether they go for the commercial stage or keep doing artistic theatre. There’s not much communication between these two worlds.

RT: What new developments should we expect in the near future?

Hashimoto: As long as there will still be some subsidies for art and culture, we’ll be able to hang on for a couple of years. But I wonder if there will still be such financial support in ten years from now. In the regions outside of Tokyo, nothing will change much from this point of view because the subsidies for cultural activities are scarce even now.

From the artistic point of view, there will be fewer and fewer stories with a linear development. I think we will witness the advent of a type of dramaturgy that is different from what we know at present. Theatrical collages or incorporating music in a theatrical work will become more common. We’ll probably see more artists approaching theatre from a dramaturgical or directorial perspective rather than through acting. The current young generation looks up at artists like Chelfitsch or Chiten. They are also heavily influenced by music. In their works, a dialogue is not such a strong component anymore. In most of the cases, it’s monologue.

RT: What are your recommendations for someone who comes from abroad in Japan and wants to experience the Japanese theatre scene? What should they start with?

Hashimoto: To theatre-goers visiting from abroad, I would recommend watching performances featured in festivals, because the programs are curated. In public theatres, only part of the program is curated by an artistic director. The theatres simply rent their stages to companies who need a stage to release their work, so there is almost no guarantee regarding the quality of those works. The only theatre that actually performs a selection of the works hosted by their stage is Komaba Agora Theater in Tokyo (*9).

In Japan, theatre curation is a very difficult task. At an art exhibition, for example, visitors pay 2000 yen for a ticket and they get to see several works of art. They won’t think that the ticket price means paying for the works. It’s just an entry ticket. But at the theatre, the audience pays for the work itself. If it’s not interesting enough, they might as well ask to receive their money back.

At Kyoto Experiment, the main purpose of curation is to introduce new artists and new ways of expression to the audience to let them know just how interesting can theatre be.

Moreover, in Japanese culture, people still have mixed feelings about having one person deciding something. Everything is usually decided by common agreement to avoid confrontations. That’s why “curation” is an activity that is frowned upon by many. Getting along well with everybody and getting the program which you think is good through is really hard. Somehow, I’ve been managing to do it for the past few years. Even if I were to disappear, I would like this curation system to continue. This is what I’m striving for at the moment.

Notes:

*1 Shiro Maeda… Playwright, theatre director, novelist, screenwriter. Founder and director of the theatre company Gotandadan. Received the Kishida Kunio Drama Award for the play Ikiteiru mono wa inai no ka? (“Isn’t Anyone Alive?”) in 2008.

*2 Masataka Matsuda… Playwright and theatre director. Founder and director of the Kyoto-based theatre company Marebito-no-Kai.

*3 Chiten… Theatre company founded in 2001 and lead by director Miura Motoi. Chiten is known for their distinctive style of creating multi-layered performances in which the actors’ physicality, words, sound, light, and time are combined to shed a new light on complex classical plays.

*4 Akira Takayama… Theatre director. Founder and leader of the theatre unit Port B, which is active since 2003 and is known for site-specific works.

*5 Ryoji Ikeda… Experimental musician and artist based in Paris and Kyoto. Sound creator for the performance collective Dumb Type.

*6 Small theatre… A term referring to theatre venues with less than 300 audience seats. By extension, the term refers to the theatre companies that create and perform works expressly for the stage of small theatres, keeping a distance from mainstream and commercial theatre productions.

*7 Toshiki Okada… Playwright, theatre director, and novelist. He founded the theatre company chelfitsch in 1997. Their distinctive theatrical style can be described through the use of hyper-colloquial Japanese language and a choreography that separates the actors’ bodily movements from their words.

*8 Daisuke Miura… Playwright, theatre director, film director. Founded the theatre company Potsdoru in 1996. Received the Kishida Kunio Drama Award for the play Ai no uzu (“The whirlpool of love”) in 2006.

*9 Komaba Agora Theater… A theatre located in Tokyo’s Meguro ward. Directed by theatre playwright and director Hirata Oriza, founder and leader of the theatre company Seinendan.

The interview was taken on May 12th, 2018 at the Kyoto Experiment Office in Kyoto.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ramona Taranu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.