Current Location (Genzaichi in Japanese), written and directed by Okada Toshiki, founder of the theatrical unit Chelfitsch, was performed for the first time in April 2012 at KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theater in Yokohama. It has been performed again several times – in Rakvere, Hamburg, and Essen in 2012, in Seoul, Paris, and Tokyo in 2013, and in Berlin in 2014.

Chelfitsch – An Introduction

Chelfitsch has been active since 1997 and is known for its original performance style, which makes use of colloquial language and “noisy” physical movement. Separating the discourse and the gestures on purpose results in a bizarre choreography that distracts the attention of the audience from what the characters are saying and directs it to the image that lies beyond the words and the gestures. The method employed by Chelfitsch hints at the potentiality of theatre to question the very basic things that are usually taken for granted.

You can get a glimpse of their style by watching the presentation video of Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and the Farewell Speech:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjOJemiOUUY&list=PL16E4B6D5E69C6957&index=1&feature=plpp_video

The language that Okada Toshiki uses in his plays faithfully mimics the everyday speech of contemporary Japanese youth and one of its interesting traits is that the characters are often talking about things without naming them. This kind of verbal expression is nonetheless a characteristic of Japanese language, in which the subject of a sentence can be easily elided, with the communicative act still making sense.

After Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and The Farewell Speech, plays like Five Days in March and The Sonic Life of a Giant Tortoise have gained high acclaim even outside Japan for exploring social and individual issues through theatre, in a bold and unconventional attempt to find new meanings for theatrical expression. In Okada Toshiki’s own words (from the pamphlet of Current Location), he conceives theatre as a “mirror.” According to him, what theatre can do is to raise a mirror to society and to show an image of reality, in the hope that a change for the better would occur if there’s a need for it.

Before taking a closer look at Current Location, here’s a short video of a scene from Five Days in March, which will get you acquainted with the performing style of Chelfitsch:

Current Location – The Power of Fiction to Shake Reality

Given the predilection of Chelfitsch for taking on the most actual and most relevant issues of the present, it was only natural that their 2012 work Current Location would mirror the state of the Japanese society after the disaster triggered by the earthquake on March 11th 2011.

From an article entitled “Menacing Reality Through Fiction” (Theater der Zeit, 10/2011) we already got a glimpse of the direction which Okada Toshiki’s work would take after the events from 2011. He was acknowledging theatre as fiction and raising questions about what can fiction do in order to give a stimulus of some kind to reality. The disaster which afflicted Japan in 2011 had been a turning point for him as a playwright, such as it had been for the Japanese society as a whole.

Okada insists that Current Location should be seen as fiction, and goes as far as pointing out the science fiction elements of the play, in an attempt to detach the story from the disaster that marked the year 2011 in Japan.

The characters of Current Location – all women – are tormented by the rumors that a disaster is set to happen to their village. While some believe the rumors and want to leave at once, others don’t see any reason to take action, though they are also obviously disturbed by the rumors. While the seemingly unconcerned ones attempt to live their lives like they used to, one of the characters is murdered. No one knows her whereabouts until the lake near the village dries and reveals the body. On the same occasion, the villagers dig up a ship found at the bottom of the lake, which they see as a means to leave the crumbling village forever. Some of them do leave – thinking with regret that the world they left behind would have already disappeared. But some of them remain, only to witness a long-lasting rain that menaced to flood everything. It turns out that the rain fills the lake back, and the village flourishes once again.

The option for an all female cast seems to have been motivated by the same urge to underline the fictional character of this story. While each of the characters has her own way of dealing with the critical situation, the overall view is of an ambiguous state of affairs, impossible to grasp in its entirety. There is no final, clear-cut answer, in spite of the urgency to find one. In order to suggest the viewers that the story unfolding on the stage concerns them directly, the characters even stage a play within the play. In this way some of them become spectators themselves, breaking the imaginary division between stage and audience known as “the fourth wall,” and letting the viewers realize that they are involved in this story.

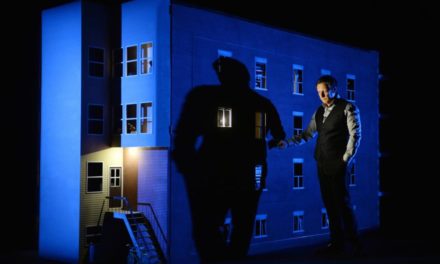

Nevertheless, the most disturbing thing about Current Location is that the choreography which was the trademark of Chelfitsch has been left off. With the “noisy” physical movement being replaced by restrained gestures, the result must have been a shocking sight for the viewers accustomed to their performances, as the silence of the gestures proves to be far more unsettling than the that of words. More than anything else, this almost unnatural absence of movement is the mark of a dramatic change undergone by Chelfitsch after March 2011.

Long after the performance, there was a phrase that still lingered in my memory: “Those who keep their eyes closed, end up dead.” This is probably the only direct statement in the whole script and the only point where the author leaves his unintrusive stance aside. For a single moment, when this phrase was uttered, the image in the mirror became menacing, appealing to the consciousness of the audience directly.

The plot of Current Location and its resemblance to the state of the Japanese society after March 2011 may be overwhelming to anyone living in Japan at the moment, but Okada insists that his intention was to conceive a fictional work, powerful enough as to shake reality. After all, the act of checking our current location is in itself a sign that we are on our way toward a new horizon, and hope is not lost as long as we keep going forward.

Audiences from any generation and any place in the world will be able to link this strangely painful story to their own anxieties and to see their own image reflected in the mirror, urging them to take a step toward the self they desire to be.

*This article was first published on Stories of the Mirror, a Japanese theater review blog. Reposted with permission of the author.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ramona Taranu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.