Courtesy of Paweł Zapendowski

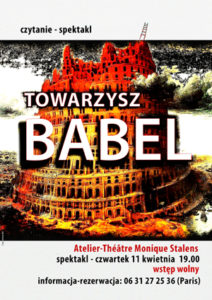

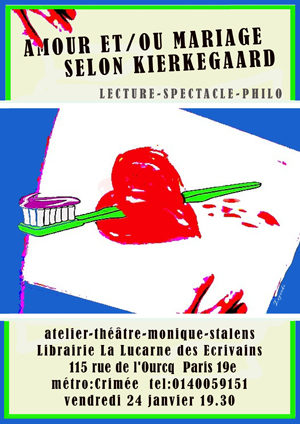

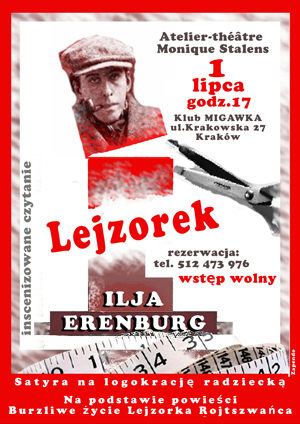

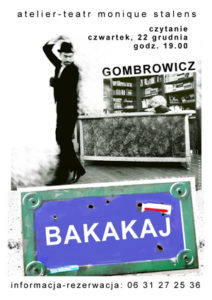

Today, Monique Stalens often directs her theater adaptations of Gombrowicz and Witkacy in Polish, the language that her mother was forbidden to teach her. During rehearsals, when she occasionally doesn’t know a word, she uses the French equivalent but then reverts to Polish. At seventy-six, she is flexible and supple, thanks to her many years of tai chi practice, and she demonstrates exercises for her actors that help them to breathe, relax, and focus on their bodies and voices before they begin working on the play. Stalens stages performances in Poland and France, and when there is no theater space available, she even transforms her Paris apartment into a stage. The audience sitting on the couches and chairs brings to mind the private theater events in eighteenth-century France or the clandestine performances at homes and apartments in Poland during World War II and the 1980s.

Monique Stalens

PHOTO: © Dawid H. Groński, Art Director & Fashion Photographer

I met Monique Stalens in the fall of 2004 in Paris, France. One day, while I was walking down a corridor at the École Normale Supérieure, I saw a call for auditions for a theater adaptation of Gombrowicz’s novel, Ferdydurke, which would be directed by her. When I went for the audition at the theater director’s apartment, I knew that she had an interest in Polish literature, but I didn’t know that she also had ties to Poland; I wouldn’t discover this until after our first few rehearsals. The text that had been adapted by the director was in French, and so were our rehearsals at the Rue d’Ulm. Only gradually, during occasional meetings at her place, did glimpses of her life begin to emerge. First, I noticed the French–Polish dictionary on Monique’s desk and Gombrowicz’s novel in the original Polish. I then found out that she had begun to learn Polish only a couple of years earlier, when she was sixty, even though she was born in Poland.

Monique Stalens’ story begins on April 6, 1939 in the Polishtown of Częstochowa, where she was born to a Polish mother, Julia Helena née Młynarczyk, and a French father, André Stalens. Her first few months were the last months of peace for her family. On September 4, 1939, just days after the beginning of World War II, several hundred Catholic and Jewish men, women, and children were arbitrarily picked up and murdered on the Częstochowa streets by the Wehrmacht soldiers in the event that became known as Bloody Monday. The unburied corpses remained on the streets for a couple of days to instill fear in the other residents. While the Germans continued to move deeper into Poland, the Soviet tanks rolled past the country’s eastern borders on September 17. Shortly thereafter, the Stalens family decided to flee Poland with the hope of going to France. The Germans still remembered how, during World War I, Monique’s paternal grandfather, Henri Stalens, who had directed the Motte Factory in Częstochowa, had hidden the weaving machines from them. To thank him for this selfless act, the Polish government awarded him with the order of Polonia Restituta. As the Stalens family made their escape, they saw signs of the carnage left behind by the Nazis: bombarded towns and villages, smoldering fires, and dead horses lying in the fields. They hid in the forests. Cabbage was all they had to eat. When their Mercedes ran out of fuel, Monique’s mother bought a horse so that it could pull the car. One day, the Soviet Army stopped and arrested them all. They were sent to a prison in Lwów—far from France—where they remained incarcerated in an unheated cell for several months. Stalens’ paternal grandfather caught pneumonia in prison, and his health began to deteriorate. Eventually, unlike many others who either died there or were sent to Siberia, the family had the good fortune to be released, thanks to a ransom they paid. They went to the train station, where Stalens, an infant, slept wrapped in beaver fur to protect her from the frigid temperatures. Her mother later told her that one of the Bolshevik soldiers mistook her for a piece of luggage and tossed her into the train through an open window. Although she doesn’t remember any of the details of their escape, loudspeakers at train stations still have a harrowing effect on her.

From Lwów, they went to Romania, where her paternal uncle worked as a factory director. Eventually, they left with him for southwestern France, which, during the initial years of World War II, was a free zone and the heart of the French Resistance, unlike northern Vichy-occupied France. Meanwhile, her maternal relatives who had remained in Poland continued to fight against the Nazis and Soviets. Stalens’ uncle and cousin, who were part of the Polish resistance movement, were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp and perished there.

Monique Stalens never learned Polish as a child because her paternal grandfather, who lived with them at that time, forbade her mother from speaking Polish to her. The only time she heard Polish was on Christmas Eve when her mother held her in her arms and sang Christmas carols in her native language. Her parents separated while they were in France, and in 1945, Stalens moved to Paris with her brother and mother, who suddenly found herself estranged from everything she had known and had to endure many hardships in a foreign country without her husband. She dreamed of making her own perfumes, but she had to earn a living in the French capital as a seamstress. She sent her daughter to a boarding school to ensure that she learned to speak proper French. Even though the young Monique didn’t speak Polish, at school she thought of herself as an outsider, and she always identified as Polish. “Je suis Polonaise,” she said. As an adolescent, she and her friends improvised performances based on the novels they read. She loved ballet, poetry, and music—in particular, the music of Chopin. At fourteen, Monique Stalens fell in love with Shakespeare, and especially with Hamlet, upon seeing a performance by the famed actor Jean-Louis Barrault. The following year, she attempted to read Adam Mickiewicz’s nineteenth-century epic poem Pan Tadeusz, which she knew about from her mother.

Julia Helena Stalens sacrificed everything to provide her daughter, Monique, with an education. She signed her up for the organization Jeunesses Musicales de France (Musical Youth of France) and sent her to England so that she could learn English while working as a nanny. In high school, to escape the harsh reality and poverty of her life, Monique Stalens found an antidote in literature and art. She often cut classes and went to the movies, museums, and libraries with a wealthy girlfriend. One of the films she watched during these illicit escapades was Andrzej Wajda’s Kanał, which depicts the Warsaw Uprising. Another film that influenced her tremendously was Nuit Et Brouillard (Night And Fog), Alain Resnais’ documentary on the Nazi concentration camps. Thanks to her experiences and her literary and cinematic discoveries, Stalens was much more aware of history’s atrocities than her peers. She also saw firsthand how divided the world she lived in was when her grandmother died in Poland in 1956 and her mother was unable to attend the funeral due to the political situation and the Iron Curtain that separated the East from the West. Whenever Stalens’ family received letters from their relatives in Poland, they didn’t answer them, even though they really wanted to, because they knew that the Poles who had contact with the West were victimized in their country. Monique Stalens has never been attracted to material wealth, knowing from the history of her family that material things don’t last and that the surest values are rooted in literature, philosophy, and art.

In 1958, she enrolled in Charles Dullin’s acting school, where she worked with Jean Vilar, who created the Avignon Theater Festival. She later continued her studies in a theater conservatory in Colombia, where she traveled with her then-husband, who was a mime. When she returned to France, she received her master’s degree from the Sorbonne, where she studied literature and art history. Her first daughter, Marion Stalens, was born in 1960. Today, Marion is a photographer and a documentary filmmaker. Stalens’ second daughter, Juliette Binoche, who was born four years later, is a famed actress who stars mostly in movies but sometimes also in theater. As an adolescent, Juliette starred in a play that her mother directed at the school she attended.

Notwithstanding hardships and financial troubles, Monique Stalens has remained faithful to theater throughout her life. Before becoming a director, she was an actress who performed in plays by Federico García Lorca, Jean Racine, Edward Bond, Bernard-Marie Koltès, and Sarah Kane, among others. She created a theater school at the Gérard Philippe Theater in Saint-Denis. While she taught French in the countryside to make a living as a single mother during the thirteen years she playfully calls her cultural revolution, she also staged plays after school. The first theatrical texts she wrote were fables.

In 1980, Monique Stalens saw Tadeusz Kantor’s Wielopole Wielopole, the performance that resurrected his childhood memories and brought the dead onto the stage. She found it magnificent. She was also greatly inspired by the theater of Peter Brook, as well as by Asian theater, opera, and dance (Nô, Kabuki, Beijing Opera, and Butoh).

Another event that affected Stalens profoundly and initiated her true engagement with Polish literature was the 1983 exhibit Présences Polonaises (Polish Presences) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Viewing this exhibit, she became imbued with the works of Witkacy, Gombrowicz, and Bruno Schulz. To this day, she remains fascinated by the works of these writers and by how accurate and contemporary their portrayal of humanity is. Like her life, their lives were marked by the experience of World War II. Witkacy committed suicide upon learning of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. Bruno Schulz was shot to death by a Nazi officer in Drohybycz in 1942. Gombrowicz was the only one to survive the war because, at its outbreak, he was in Argentina. Monique met Gombrowicz’s wife, Rita, in a theater bookstore in Paris, and they became friends.

Another event that affected Stalens profoundly and initiated her true engagement with Polish literature was the 1983 exhibit Présences Polonaises (Polish Presences) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Viewing this exhibit, she became imbued with the works of Witkacy, Gombrowicz, and Bruno Schulz. To this day, she remains fascinated by the works of these writers and by how accurate and contemporary their portrayal of humanity is. Like her life, their lives were marked by the experience of World War II. Witkacy committed suicide upon learning of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. Bruno Schulz was shot to death by a Nazi officer in Drohybycz in 1942. Gombrowicz was the only one to survive the war because, at its outbreak, he was in Argentina. Monique met Gombrowicz’s wife, Rita, in a theater bookstore in Paris, and they became friends.

In the 1990s, Stalens attended Jerzy Grotowski’s theater lectures at the Collège de France after he was appointed the chair of Theater Anthropology. She also took workshops with Ludwik Flaszen, who, along with Grotowski, was a co-founder of Teatr Laboratorium, as well as with Zygmunt Molik, one of the main actors of this theater. She studied Polish, first at the Sorbonne and then at the School of Polish Language and Culture of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, to enable her to read novels and plays in their original forms.

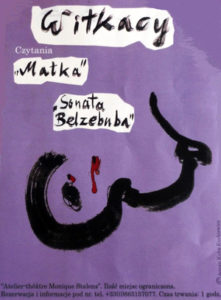

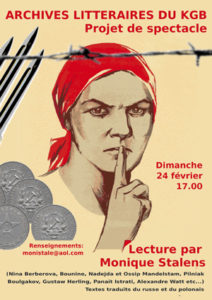

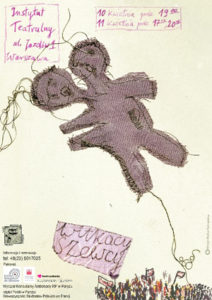

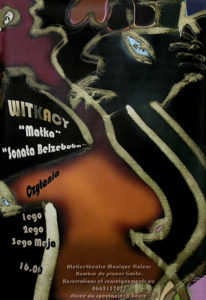

Like Tadeusz Kantor, Monique Stalens enjoys working with nonprofessional actors, and she believes that one can do theater without investing a significant amount of money into a production. For most of her life, she has worked with French actors, but today, she increasingly directs plays with both professional and amateur Polish actors. She has directed numerous adaptations of works by Schulz, Gombrowicz, and Witkacy, as well as by Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Ibsen, and others. Her theater productions exhume memories and dreams, and they are imbued with poetry and the grotesque. They are both luminous and dark and possess a timeless quality. She believes that the actor should be disciplined and humble and that theater should have a spiritual and ethical dimension like Grotowski’s theater. In her theater productions, Monique Stalens prefers no sets; it is the actors’ movements and voices, along with the imagination of the audience, that furnish the empty space of the stage.

Like Tadeusz Kantor, Monique Stalens enjoys working with nonprofessional actors, and she believes that one can do theater without investing a significant amount of money into a production. For most of her life, she has worked with French actors, but today, she increasingly directs plays with both professional and amateur Polish actors. She has directed numerous adaptations of works by Schulz, Gombrowicz, and Witkacy, as well as by Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Ibsen, and others. Her theater productions exhume memories and dreams, and they are imbued with poetry and the grotesque. They are both luminous and dark and possess a timeless quality. She believes that the actor should be disciplined and humble and that theater should have a spiritual and ethical dimension like Grotowski’s theater. In her theater productions, Monique Stalens prefers no sets; it is the actors’ movements and voices, along with the imagination of the audience, that furnish the empty space of the stage.

In 2010, the International Theatre Institute honored Stalens with the Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz Award for popularizing Polish theater in the world.

In 2010, the International Theatre Institute honored Stalens with the Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz Award for popularizing Polish theater in the world.

She continues to read in Polish, most recently the books of testimonies on Grotowski and Kantor that she received as a gift in Kraków. Tireless and industrious as she was in the past, today she leads her Atelier-Théâtre Monique Stalens in Paris, Kraków, Warszawa, and her native town of Częstochowa. She recently completed a new version of Parricides, her adaptation of Witkacy’s and Gombrowicz’s plays.

When I think of my experience working with Monique Stalens, I am reminded of the following statement by Witkacy that summarizes so well what she, too, strives to accomplish in her theater practice: “On leaving the theater, one ought to have the feeling that one has just awakened from some strange dream, in which even the most ordinary things had a strange, unfathomable charm, characteristic of dream reveries, and unlike anything else in the world.”

This post first appeared in the Cosmopolitan Review on June 6, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Agnieszka Tworek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.