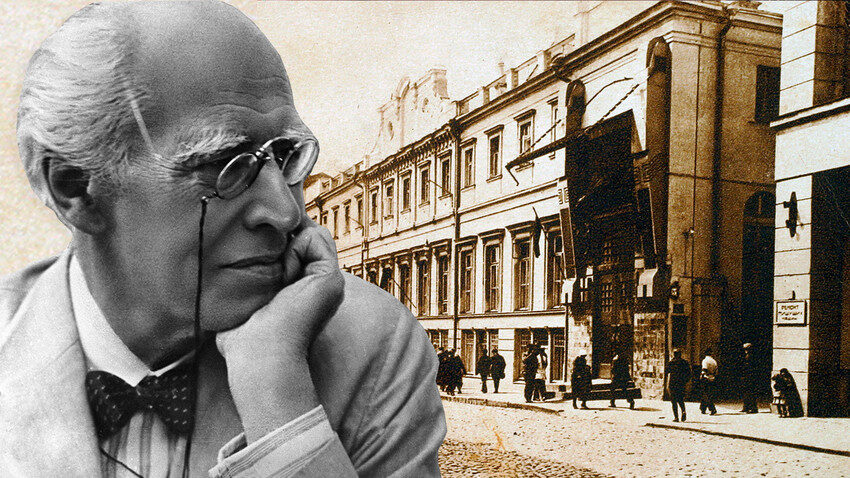

Konstantin Stanislavsky’s ideas changed the face of theater as much as Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity changed the understanding of physics. Stanislavsky wrote his name in the history books as the most influential theater practitioner of the modern era and a central mover and shaker in the world of acting and dramatic training.

The theatre was a source of palpable joy and jubilation to the tall, handsome and charismatic Konstantin Stanislavsky. A foremost actor, director, and theatre practitioner, he devoted his entire life to the Moscow Art Theater, turning an intuitive idea of what art should be like into reality. Brimming with energy and ideas, Stanislavsky was a brilliant actor, who preferred to portray two-dimensional characters undergoing major transformations. Basically, to help himself, Stanislavsky developed his own dramatic training method, widely known as the “Stanislavsky” system. Super-hyped across the world, it became the foundation for the so-called “Method” acting style.

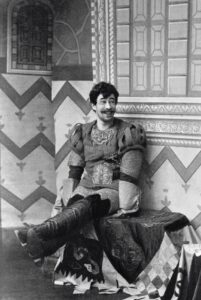

Konstantin Stanislavsky as Benedick in “Much Ado About Nothing” in 1897.

V.Shiyanovsky/Sputnik

The system, developed over four decades, is an attempt to understand how an actor, no matter what he does on stage, how tired, scared, or frustrated he or she is, can experience creative joy “right here, right now.” The system, which arose as an absolute necessity for a given person (and actor Konstantin Stanislavsky), proved to be extremely useful for a wide variety of people in a variety of practical ways in different environments worldwide. Its quintessential ingredient was faith. First of all, according to Stanislavsky, an actor has to fully believe in the “given circumstances” in which they find themselves in the play. The biggest challenge, therefore, is to learn to believe. Faith, fantasy, and vivid imagination are the three pillars of the system (which Stanislavsky modestly described as “my so-called system”).

Konstantin Stanislavsky as Gaev in “The Cherry Orchard.”

Sputnik

One way or another, one thing is certain: Stanislavsky was an outstanding teacher, whose famous students included future theater legends Yevgeny Vakhtangov and Vsevolod Meyerhold. His acting techniques and ideas had a far-reaching influence in the United States through the contribution of Lee Strasberg (the “father of method acting in America”). Strasberg used Stanislavsky’s fundamental guidelines and observations in New York’s famous Actors Studio. He coached Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Robert De Niro, and Al Pacino, just to name a few. Stanislavsky’s observations about his artistic and directorial experience provided vital clues to acting techniques worldwide.

“Stanislavsky did not invent anything. Using the example of the great artists of his time, he tried to understand, study and, if possible, master the nature of stage play,” one of Russia’s greatest theater directors, Lev Dodin, believes. “Stanislavsky wanted to comprehend the nature of human life on the stage, the nature of the birth of a new human substance on the stage, the artistic perfection of this new human being created by the imagination, nerves, intellect, and body of the artist. [Stanislavsky] was looking for ways to create this phenomenon. Therefore, when an artist plays well, i.e. convincingly, contagiously, authentically, deeply, with empathy, compassion, and joy, the artist plays according to the Stanislavsky system, regardless of whether he knows it or not.”

Family roots

It all runs in the family, they say, and it’s true that Stanislavsky, who had nine brothers and sisters, inherited his undying love for the arts from his loving parents.

The Alekseyev family in 1879.

Sputnik

Stanislavsky was born into a large and prosperous merchant family in Moscow. His real last name was Alekseyev. Konstantin’s father was a third-generation manufacturer and his mother was the daughter of a French actress.

“I was born in Moscow in 1863 – at the turn of two eras. I still remember the remnants of serfdom… I witnessed the emergence of railways with courier trains, steamships, electric searchlights, cars, airplanes, dreadnoughts, submarines, telephones – copper-wire and wireless – radiotelegraphy and twelve-inch guns. Therefore, from serfdom to Bolshevism and Communism. A truly interesting life in an age of changing values and fundamental ideas,” Stanislavsky wrote in one of his best-known works, My Life in Art.

The Alekseyev’s house was home to concerts and amateur performances, featuring adults and kids. Their guests were the crème de la crème of high society. There was a special hall set up for theatrical performances at Alekseyev’s Moscow home and a separate theater wing at their Lyubimovka estate in the countryside.

Konstantin was brought up in a place where he was free to do what he wanted. He lived to perform, and actively participated in amateur theatricals as a boy. His first big moment on stage came when he was four. The kid wore a fake beard and portrayed Russian winter.

Kostya (short for Konstantin) wasn’t the poster boy for discipline and academic performance (he didn’t like to study hard, because school studies stole valuable time from the theatre). Stanislavsky was in fact a poorly educated person.

“A drawer of the table always contained some secret theatrical work – either the figure of the character, which had to be colored or part of the scenery, a bush, a tree, a plan and sketch of a new production,” Stanislavsky recalled. “We staged many operas, ballets, or, rather, individual acts from them.” His siblings were into the theatre, too. Konstantin’s elder brother Vladimir would become a theater director and a librettist, while his younger sister Zinaida – an actress.

Konstantin’s remarkable debut on his parents’ amateur stage came in 1877 when he was 14. The young theatre aficionado joined the dramatic group called the “Alekseyev Circle.” Around that time, the future theater guru developed a lifelong habit of keeping diaries containing meticulous observations on acting. The aspiring actor’s comprehensive attention to all aspects of production set him apart from the crowd. A thoughtful and reflective artist with a keen eye for observation and detail, Konstantin became the key member of the Alekseyev Circle and began to perform in other theatrical groups.

In 1885, he adopted the pseudonym “Stanislavsky.” It was an homage to a talented amateur actor whose last name was Markov and who had performed under the name of Stanislavsky. The stage name sounded at once familiar and unique to Konstantin who, at some point, had to hide his theatrical activities from his family. His parents were open-minded people, but there was a certain degree to it. After all, acting wasn’t considered a serious profession back at the time.

Factory vs. Theatre

Konstantin Stanislavsky belonged to a family of merchants, who gained a reputation for honesty and hard work. His great-grandfather, Semyon Alekseyev, was 34 when he launched the production of gold and silver threads in Moscow. The thin thread became a sought-after item during the reign of Catherine the Great when members of a ruling aristocracy began to wear clothing embroidered with gold and silver. Thanks to Alekseyev’s golden thread factory, all that glittered was indeed gold, especially at royal receptions and balls, where ladies’ dresses were embellished with gold. The men’s ceremonial uniforms were adorned with precious threads made at the Alekseev factory. On top of it, the threads decorated vestments for priests. Alekseyev’s company was highly successful.

Vladimir Alekseyev, Konstantin’s grandfather, made waves when the gold thread factory that he had inherited became the first Russian company to mechanize production in the 1870s.

Like father, like son certainly applied here. Sergei Alekseyev also expected his beloved son Konstantin to go into the family business. Stanislavsky gave it a go, running the Alekseyev factory for a while. It was a sacrifice on his part, even though he had never really put the theatre on the back burner.

Stanislavsky proved to be a talented businessman. For instance, he managed to improve a sewing machine designed for stretching the thread. Stanislavsky even traveled to the UK to obtain a patent for his update. The measure helped open up new horizons for the company, boosting revenues. The Alekseyevs donated money to help build hospitals, schools, and museums. Their companies were nationalized after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Love for acting

In 1888, Stanislavsky met his future wife, Maria Perevostchikova, an up-and-coming young actress, who performed under the stage name of “Lilina.” For a while, neither Stanislavsky nor Lilina suspected that they were actually in love with each other. “We found out from some audience members. We kissed too naturally in the play, they said.” The two actors got married a year later and had three children. Their marriage lasted fifty years.

Konstantin Stanislavsky and Maria Lilina.

Sputnik

The unrivaled genius in the world of acting and theater kept his diaries religiously and left a legacy of over a dozen groundbreaking books on directing and acting skills, character development, and self-reflection. “Never lose yourself on the stage. Always act in your own person, as an artist. The moment you lose yourself on the stage marks the departure from truly living your part and the beginning of exaggerated false acting. Therefore, no matter how much you act, how many parts you take, you should never allow yourself any exception to the rule of using your own feelings. To break that rule is the equivalent of killing the person you are portraying because you deprive him of a palpitating, living, human soul, which is the real source of life for a part,” he wrote in his book Actor’s Work, full of practical advice for aspiring actors.

“In theater, I hate the theater,” Stanislavsky famously said, meaning fake theatrics and chest-thumping. “One must burn the old ships and build the new ones,” he believed. Stanislavsky changed theater and was changed by it, too. In 1888, he established the Society of Art and Literature with a permanent amateur company that he funded himself. This was his creative learning laboratory for ten years. There, Stanislavsky worked on the plasticity of his body and voice. He had proved his acting chops, shining in comedic and dramatic roles, winning accolades from established actors.

Konstantin Stanislavsky changed theater and was changed by it, too.

Sputnik

Stanislavsky also mastered the art of directing. He made his directorial debut with an 1889 production of Peter Gnedich’s “Burning Letters.” Marked by psychological restraint, the actor-turned-director paid special attention to dramatic pauses and choreographed moves that spoke louder than words. A master of mise-en-scene, the trailblazing Stanislavsky found some alternative ways to emphasize the drama on stage, spicing up his productions with light, sound, rhythm, and tempo.

The growing dissatisfaction with the state of the Russian stage at the end of the 19th century, the feeling that it’s time to separate authentic traditions associated with the very nature of acting from theatrics and the determination “to give more space to imagination and creativity” prompted Stanislavsky and his partner in crime, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, to unite efforts, banding together with their artistic goals and their troupe of actors.

Duo with Nemirovich-Danchenko

Meeting Russian playwright, director, and producer Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko was, in fact, a turning point for Stanislavsky.

Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko and Konstantin Stanislavsky.

Sputnik

The historic meeting, which took place in Moscow in 1897 and lasted 18 hours (at the Slavyansky Bazaar restaurant), led to the creation of the Moscow Art Theatre. “We are striving to create the first rational, moral public theater and we devote our lives to this lofty goal,” Stanislavsky stated.

The Moscow Art Theatre opened in 1898 with Aleksey Tolstoy’s tragedy “Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich,” with Nemirovich-Danchenko’s student Ivan Moskvin in the limelight. It was a success, but Stanislavsky was unhappy with the actors’ acting. He found it flat, imitative, lacking genuine emotion. A strict and demanding teacher, he called for authenticity on stage, handing down his famous verdict to actors after hours of fruitful rehearsals: “I do not believe you!” He urged actors to bond with their characters, to inhabit them, find their vulnerabilities and insecurities.

Vasily Kachalov, Maxim Gorky, and Konstantin Stanislavsky with the Moscow Art Theatre actors.

Sputnik

For the first several years, the performances that marked the formation of the new theater were created jointly. It was difficult to single out the “exact share” contributed by each of the two partners, Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko. In historical dramas like “Tsar Fyodor Ioannovich” (1898) or “The Death of Ivan the Terrible” (1899) Stanislavsky took the lead, whereas working on “Julius Caesar” (1903), Nemirovich-Danchenko acknowledged that he was a student of Stanislavsky. In the beginning of their work, they were like two equal sides of a regular quadrilateral.

Nonetheless, it was Nemirovich-Danchenko who encouraged Anton Chekhov to write for the theater. After Chekhov’s “The Seagull” failed miserably at the Aleksandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Nemirovich-Danchenko persuaded Chekhov to greenlight the staging of his play at the newly-formed Moscow Art Theatre. It marked the beginning of a new era for the theater.

Stanislavsky later said that while working on “The Seagull” in 1898, he had not yet figured out the new dramatic tradition created by Chekhov. It was while staging “Uncle Vanya” (1899), “The Three Sisters” (1901), and “The Cherry Orchard” (1904) that he found a key to the inner world of the author.

Konstantin Stanislavsky as Astrov and Olga Knipper as Elena Andreevna in Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” in 1899.

Sputnik

And yet, there was a rivalry between Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko. The fruitfulness and conflicted nature of the Moscow Art Theatre founders was reflected in the work on the triumphant production of Maxim Gorky’s “Lower Depths” (1902).

While at first, both Konstantin and Vladimir sat comfortably at the director’s table preparing one performance, after 1906, things went off track. “Now each of us had his own table, his own play, his own production. This was neither a discrepancy in the basic principles nor a rupture, it was a completely natural phenomenon.” Because, as Stanislavsky wrote, each of them “wanted and could go only along his own independent line, while remaining true to the general, basic principle of the theater.”

Russian soul

Russians have a passion for performances that touch the heart, Stanislavsky believed. “They enjoy dramas where one can cry, philosophize about life and listen to some words of wisdom more than perky vaudeville shows that empty the soul.”

Konstantin Stanislavsky as Famusov in Alexander Griboedov’s “Woe from Wit.”

Sputnik

As an actor, Stanislavsky was brilliant as Astrov in Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya,” Vershinin in “The Three Sisters,” Gaev in “The Cherry Orchard,” Satin in Maxim Gorky’s “Lower Depths,” Famusov in Alexander Griboedov’s “Woe from Wit.” Both Russian and European critics were impressed with these roles, but Stanislavsky couldn’t just sit back and rest on his laurels. He never stopped setting new goals.

Thanks to breathing and relaxation practices, Stanislavsky, nearly 6-foot-6 (198 cm) managed to turn his b

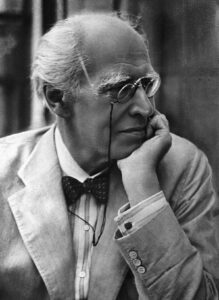

The unrivaled genius in the world of theater left a legacy of over a dozen groundbreaking books on directing and acting skills.

B.Brilliantov/Sputnik

ody into an obedient instrument, capable of conveying practically any emotion.

In the early 1920s, the Moscow Art Theatre toured Europe and America with Stanislavsky as its director and lead actor. But after a severe heart attack sent Stanislavsky to the hospital in 1928, doctors forbade him to perform on stage. The indefatigable practitioner went back to work only in 1929, focusing mostly on theoretical research, on pedagogical activity, polishing his new “system” and focusing on classes at his Opera Studio, which had existed since 1918 (the Stanislavsky Opera Theatre).

In terms of his maximalist demands, Stanislavsky could probably be compared to Fyodor Dostoevsky or Leo Tolstoy, both of whom had a great influence on him. Tolstoy was a great role model for a number of Russian artists, who tried to adopt his unique and vital sense of life, his honesty, and truthfulness. Like a doctor constantly checking a patient’s pulse, the indefatigable Stanislavsky had to make sure over and over again, whether his art was not becoming an end in itself. “It’s a mistake to think that an artist’s creative freedom lies in doing what he wants. This is the freedom of a petty tyrant. Who is the freest of all then? The one who has won their independence, since it is always won, not given.”

This article was originally published by Russia Beyond (https://www.rbth.com/). Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Valeria Paikova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.