Every soldier has a story to tell–sometimes a joke, sometimes a parable, often a tragedy. The simple genius of Lola Arias’s Minefield is that it gathers together and places on stage the stories of six veterans from two opposing sides. Even the fact that theatre can make this possible is enough to send tingles down your spine. But then there is more: soldiers, like actors, are likely to have quite a bit of physical prowess to put to good use in a theatrical performance, and–to make more of another cliché–they often play music too. The latter will gradually become a secret ingredient that really makes this show stand head and shoulders above many others.

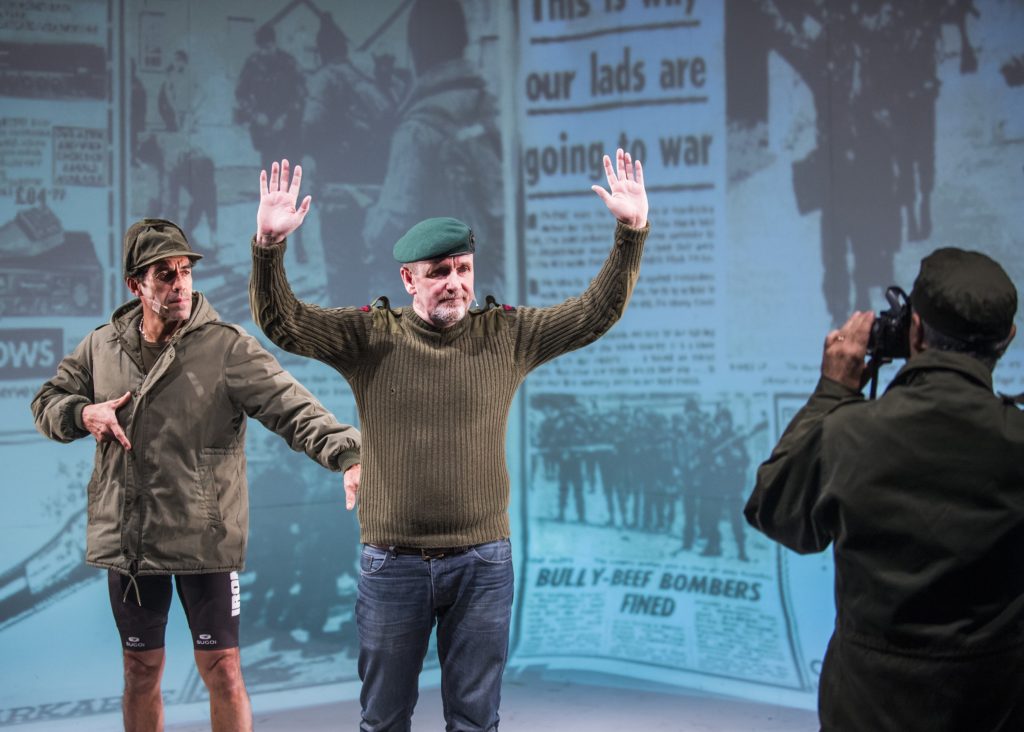

A scene from Minefield by Lola Arias @ Royal Court, Jerwood Theatre, Downstairs. Developed by The Royal Court and LIFT. Photo: Tristram Kenton

But to start from the beginning: for the last ten years, Argentinian theatre-maker Lola Arias has built an international reputation as an artist who places real life on stage–beggars, prostitutes and street musicians of Bremen in The Art Of Making Money (2013), for example, but also her own and her collaborators’ autobiographies in other multiple works. She is also known as a poet, visual artist, and a musician, all of which informs her theatre work. Though she has worked extensively in Europe, Minefield, made in collaboration with LIFT festival, Brighton Festival, and the Royal Court, was her first major British collaboration in which she revisits the events of the 1982 Falklands/Malvinas war between the UK and Argentina. Following the initial sell-out run in 2016, the show is back on at the Royal Court for a brief reprise.

The piece has a very straightforward and seemingly unambitious structure–the soldiers start by telling us about who they are, how they became soldiers, and then how they entered into the war. The delivery is dynamic and although they are not trained performers, the unlikely ensemble members have clearly been taught various storytelling and performance techniques during the year-long development process. They have been asked to keep diaries of the rehearsal process, and at times they share small extracts with us in spare, but well placed, moments of metatheatrical commentary.

The centerpiece of Mariana Tirantte’s set is a curved projection screen, made to resemble an open book perhaps. This is where photographs and complementary footage of landscapes are projected. On the right there is a desk with a suspended camera connected to the projection screen via live feed, so the performers can display their personal documents, maps, props, or manipulate toy soldiers in the process of evoking memories. On the left – a drum kit, and some everyday objects which are used to create foley sound effects at suitable dramatic moments. Newspaper cover stories are literally brought to life here, documentary footage of politicians’ speeches (Margaret Thatcher’s and Leopoldo Galtieri’s) is lip-synched to by the performers wearing full head masks representing these real-life protagonists, death is recounted first-hand. Like many previous artworks about war, this one also makes the point that war more easily happens between groups manipulated by power figures rather than between living breathing individuals. So if, like Marcelo Vallejo, one always dreamt of meeting a representative of the other side to take their anger out on them in person, they soon found out that eye to eye–and heart to heart–contact made this compensation impossible.

A scene from Minefield by Lola Arias @ Royal Court, Jerwood Theatre, Downstairs. Developed by The Royal Court and LIFT. Photo: Tristram Kenton

Nevertheless, it’s not so much the stories of combat, different sides of history or even ultimate reconciliation that this show is about. The somewhat seemingly clunky sequence of scenes covering each soldier’s time in the war from arrival, via the sinking of the Belgrano ship and other significant military or personal moments, to their eventual homecoming, is only a preamble to the final and most significant part of the show in which the soldiers explore the personal after effects of their military experience. Many were still in their early twenties when they returned and so the war was only the beginning of the rest of their lives. Variously they dealt with the post-traumatic disorder by taking drugs, or isolating themselves, or traveling, receiving therapy and even learning to give therapy to others. Today, as men in their 50s and 60s, they have other professional identities, hobbies and occupations–doing sports and music, psychology or criminal law–but all the same, the memories remain.

In putting many disparate aspects of this complex and deeply conflicted shared life experience together, Lola Arias’s craftsmanship is truly remarkable. The choice of a very linear dramaturgy serves to open the space for real-life stories and real-life performers to find their own way to the audience. Meanwhile, the director provides carefully chosen tools for performative storytelling to take place, taking care of the overall rhythm of the piece and making sure moments of humor, feeling and reflection succeed each other in equal measure throughout the piece. In shaping the material, Arias’s contribution is comparable to that of a musical composer, which is no mean feat in this particular, kind of symphonic, context.

My Swiss companion on this occasion, who happens to be more familiar with Arias’s earlier works, described the director’s approach as a “punk aesthetic.” This rings true on the level of the musical content of the piece, but it is even more accurately reflective of the iconoclastic, angry and impassioned prioritizing of raw matter over any kind of virtuosity or artifice. The six men simply come before us with who they are and what they have, warts and all; they bleed and they cry and they grit their teeth, and they shine too! Especially when they drop their weapons and pick up their guitars, drumsticks, and microphones to play music together. This is where each one of them is at their absolute natural best–and it just goes to show that if there is ever a way to achieve world peace, rock’n’roll must have something to do with it!

A scene from Minefield by Lola Arias @ Royal Court, Jerwood Theatre, Downstairs. Developed by The Royal Court and LIFT. Photo: Tristram Kenton

Royal Court Theatre, London

November 2-11

Written and directed by Lola Arias

With Lou Armour, David Jackson, Gabriel Sagastume, Ruben Otero, Sukrim Rai, Marcelo Vallejo

Research and production: Sofia Medici, Luz Algranti

Set: Mariana Tirantte

Music: Ulises Conti

Lighting: David Seldes

Video: Martin Borini

Sound: Roberto Pellegrino, Ernesto Fara

Costumes: Andrea Piffer

Co-producers: LIFT festival, Brighton Festival, Royal Court Theatre, Universidad Nacional de San Martin, Theaterformen, Le Quai Amgers, Künstlerhaus Mousonturm, Maison des Arts de Créteil, Humain Trop Humain/ CDN de Montpellier, Athens & Epidaurus Festival, The Sackler Trust

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.