Michelle Memran is the documentarian behind The Rest I Make Up (2018), a touchingly candid portrait of Cuban-American playwright and director Maria Irene Fornes. A revolutionary figure in the off-Broadway movement of the late twentieth century, Fornes’s creativity and vivacity was not stopped by her later fight with dementia. Memran captured it all with joy, friendship, and artistry. I was fortunate enough to sit down with the brilliant director herself to discuss her process on this film and how she became part of Irene’s family.

Rhiannon Ling: Let’s go all the way back to the beginning. Were you drawn to Irene before you met her in the early 2000s?

Michelle Memran: I went to school for journalism, but I so desperately wanted to be a playwright. I took a couple of playwriting classes in college. In one of the classes we read a play called The Conduct of Life, which is a brilliant short play of Irene’s, and I read a monologue by a character named Olympia that was like nothing I’d ever read before. The play was like nothing I’d ever read before. I sought all of her work because I was just reading plays as much as I could, and then I started writing about theatre. I started writing about playwrights, in particular because I just loved them so much. A teacher of mine was Jules Feiffer, who was another playwright; he taught a class called “Humor and Truth.” I took that with him, and he became a mentor of sorts to me. One night, we were at dinner, and he was talking about how he got back at a critic who had wronged him by calling him out at the Obie Awards or something. And he said, “You should write an article! You should do an article about playwrights retaliating against critics.” And I thought that would be really interesting. I started researching this article without any idea of where it was going to go, and I interviewed like fifty people. The list went on and on, all these playwrights. Then I thought, well, my favorite playwright I haven’t called. I just looked [Irene] up in the phonebook and she was listed, and so I called her up, and she agreed to meet me. She was by far the playwright I was most intimidated to talk to, but also my favorite. She had no interest in answering any of my questions, and we talked about everything else for like six hours. That was the first time we met. Then, after meeting her, I, of course, had to find out everything I could possibly find out about her personally, because I was like, “Who is this magical being?”

Ling: Clearly, you have a lot of experience with writing for and about the theatre. Were you ever interested in being a documentarian before this piece?

Memran: No, never.

Ling: Do you remember when you consciously decided that this was going to be a full piece? What brought you to make that decision?

Memran: I don’t think I consciously thought it was going to be a full piece until it actually, 15 years later, became a film. There was a moment that we went to Brighton Beach, and we had this Hi8 camera that my father had gotten me. We pulled it out—it was 2003—and there was that moment that you see in the film, where I say, “Irene, does the camera make you uncomfortable?” And she says, “Oh, no, the camera to me is my beloved!” That was the moment where I was like, something is happening with the camera and Irene, so what if we do something? I called her agent immediately after we got back from Brighton Beach, and I said, “Something happened. I have to show you this footage. What if we worked on some kind of film project, where I’m just documenting her doing camera monologues or I show up at her house with her camera once a week, capturing memories?” At that point, we had known that her short-term memory was not great, and that there was something going on, but we didn’t know what it was. So, Morgan [Irene’s agent] was like, “If there’s a creative collaboration you want to do that Irene is game for, you gotta do it.” I talked to Irene about it, and she was like, “Sure! Of course! I’d love it!” There wasn’t necessarily a moment of “we’re going to make a film with this” at that time. I would call Irene up, and she would say, “Do you want to work today?” She would start asking me. I had a job at Vanity Fair. I would leave work on my lunch and go see Irene. We’d spend two hours, and I’d go back up to work, which was a longer lunch hour than I probably should have been taking. So, it was this thing that we were doing, but it wasn’t necessarily going anywhere. Then, I started interviewing other people. It was a way, in my mind, to alert people to what was happening with Irene, to also widen the community and widen the circle of people coming to visit. So, I went down this list, and I said, “Just tell me if you love them, hate them, or don’t remember them.” She went down and she said, “Love. Hate. Love/hate. Don’t remember. Don’t know who you’re talking about. Love!” I was calling up these people and saying, “Hi, I’m a friend of Irene’s. We’re making a documentary. Could I come to interview you about her?” Most people were like, “Sure, okay!” I went and interviewed Larry Kornfeld, who directed Promenade, and after our interview, I got a call from him, saying that he had mentioned the project to someone else and they wanted to help me. I got a call from this fantastic actress and theatremaker, Wendy Vanden Heuvel. She ended up becoming our executive producer of the film. That day, she watched footage [of] Irene on the tiny camcorder and she was laughing and laughing. She gave me a grant that got us going, and then continued to support the film throughout to its completion. When she believed in this project as much as she did, it felt like we were making something more than just a home movie. And that’s when we decided to go to Cuba, with the grant money. That’s the way it sort of happened throughout the life of the film: the support we’ve gotten from people from Irene’s past, as well as the film community, gay and lesbian community, New York State Council of the Arts…so we just sort of started piecing together funds, but the true heart of the support is from the theatre community.

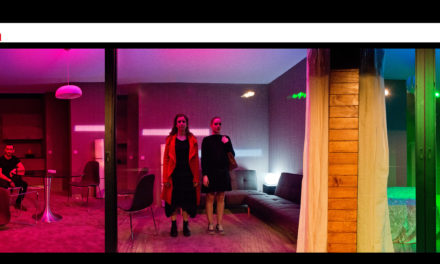

Maria Irene Fornes and Michelle Memran in Seattle, 2005. PC: Michael Smith

Ling: I want to jump back a little bit. You were talking about widening the circle around Irene and bringing people in. As the years went on and as dementia progressed, did you find it difficult on yourself to keep filming?

Memran: Yeah, I think it was difficult. In the film, there are certain moments where the camera’s not on her directly, because I’m uncomfortable filming her in vulnerable moments. Basically, I filmed for fifteen odd years, but more on and off as the years went on. In the edit, we decided that, even though I had all this footage from after she left Miami when Irene stops recognizing what the camera is and what we’re doing together, the film’s over. So, we couldn’t use footage from that point on. We have some audio from, like, 2010, but really past 2006, we don’t show any images of Irene. I think there’s a couple, from much later, but very few. It became increasingly difficult to film after about 2006, where she was moved to an assisted living facility, and then various nursing homes. We went and visited; at that point, I was family, and it wasn’t really about making the film at that point, it was just about, I miss Irene, and I’ll just bring the camera. Sometimes I’d pull it out, and sometimes I wouldn’t. The fun of it was her knowing that the camera was there, and her responding to the camera, and her getting such delight out of being photographed and filmed. That was fun, and that was the excitement, the was the charge of it. When she’s not participating, it lost that energy, and it lost our purpose. That purpose was a joy.

Ling: Was there ever any thought, before she stopped recognizing the camera, of editing any of her struggles out, or was it intentional to leave most of it in?

Memran: It was intentional to leave it all. Over the years, we had done samples for grants and for presentations, and, in 2010, we had a birthday party for her, and we showed the twenty-minute sample. That was the closest she came to the premiere. That was the moment where she got a standing ovation; it was really sweet. Then, the next morning, we watched the film again, and we went through it. I just wanted to make sure she was okay with all of the scenes about her memory. And she was hilarious. She said, “You keep talking about how I lost my memory. I never had it to begin with; I was born without one!” I said, “So, is there anything you’d like me to change in what you just saw?” And she was like, “More me! I’d like more me!” I felt pretty liberated at that moment. She’s not one to shy away from the dark side. She’s not afraid to go to the ugly places, to the real places. Her plays and the way she approached her theatre-making allowed me to go to those places, too.

Ling: I was curious, too, after you talked to her in Cuba about being a lesbian: was there ever any hesitation about including that? Did the family get to see it, and did they say anything afterward?

Memran: The family knew; it just wasn’t something that came up in conversation. Irene had been to Cuba with Susan Sontag in the ‘60s. Her brother had told this whole story about Susan getting caught in the window, trying to sneak out or something. They knew what was going on. I don’t think Irene brought her partners around that often, or, if she did, maybe they were friends. When I tried to ask her family in Miami questions about Susan, they quickly changed the subject. It was something that just wasn’t talked about. I didn’t bring it up with her family, and it depended on the day if [Irene] wanted to talk about it or not. She was a private person; she says in the film, “My life is my life, and I don’t give a damn what they say.”

Ling: Changing gears a little bit, how did you decide when to take the camera out? Did you preplan any of it?

Memran: It was all freeform. I had my camera with me wherever we went, and I mostly captured all of it. A lot of it was just us hanging out in her apartment. There were some shoots we set up, like the Drama Book Shop in the middle. In Cuba, I brought a cinematographer with me: that was the first time you actually get to see me. That was intentional. I knew that I didn’t know what I was doing with a camera in that way, so it would be bad if it was just me in Cuba. That was planned, but the moments in Cuba were not planned. We’d wake up in the morning, and I’d say, “Should I get the camera?” Or I’d just get the camera, and she would wake up and there’d be a camera in her face, which for some people would be incredibly irritating, but Irene was delighted by that. We had over 500 hours [of footage]. I mean, that’s a little amount these days; I’m working on a documentary right now that’s 1500 hours. I think [the editing is] when I got overwhelmed and I put the project down for a couple of years. Then we did a Kickstarter, and it resuscitated the project; I finally met the editor I was going to collaborate with. That was the biggest piece to actually finishing it, because it’s a non-linear story and it is a bit unconventional. Everything was fragmented, so how do you stitch together fragments to tell a story? She [our editor] was able to do that, miraculously.

Ling: Is there one particular fragment, whether it ended up in the film or not, that sticks with you?

Memran: Oh, there’s so many. We’re working on a book right now of outtakes from the film, so I have a lot of Irene-isms in my head. There’s one moment that was in every sample we ever did, and it didn’t make it into the film. I walk in, and I say, “Who is Irene Fornes?” And she bends over and picks something up, and comes back and says, “Irene Fornes is this person. She is very, very, very beautiful. She is very, very, very smart. She is a dancer like Pavlova—sheesh! She’s nothing to compared to her!” She goes off on this whole thing about who Irene is, and she’s like, “When Irene sleeps, nobody sleeps like Irene. She is like an angel dreaming of other angels and of movie stars.” It’s this beautiful thing that she says. It didn’t fit into the way we wanted to introduce her, but it’s one of my favorite moments.

Maria Irene Fornes in 2010. PC: Michelle Memran.

Ling: Is there any lesson, either from the making of the film itself or from Irene herself, that has really stayed with you since completing the project?

Memran: One of the things that—especially for theatremakers—will come up in some of the Q&As will be, “How did you decide not to include her plays?” That was a big thing that came up in the making of the film. We had a dramaturg, who’s a Fornes scholar, go through, and we cataloged all the plays by the theme that matched the footage. We didn’t really know what we were going for, but the idea was to have her plays in there. Then, when I met Irene, she didn’t remember having written most of her plays, so, for it to be a collaboration, we decided that we only could use Irene’s own memory: if she didn’t remember it, it didn’t belong in the film. If we were to do sections on the plays, we would be inserting other people talking about the plays, but she wouldn’t be able to talk about her plays. That was not my story to tell. The only thing I could tell was our experience. That was interesting because what you come away with is not a scholarly interpretation of Irene Fornes’s plays. You come away having spent 75 minutes with the playwright, with the person. The biggest lesson in that has been, by getting to know the playwright, you’re getting to know about every aspect of the work. That was revelatory in that sense: it’s like taking a masterclass with Irene in a lot of ways. The most striking thing has been how audiences have responded to her, in the same way that I responded to her. That’s been really affirming. I’ve been really bowled over by the reaction to her as a person and to the collaboration.

Ling: Have you found that people, after watching your documentary, develop more of an interest in Irene?

Memran: Yeah! That was the point; that was the mission. There have been more productions of her plays since: the film has had a small part in the resurgence, I think. There’s a Fornes Institute, which is dedicated to her legacy and to doing Irene Fornes workshops. It’s amazing because she never wanted to be labeled and pigeonholed, but all of these different factions have come together now to help move her work forward. That has worked in her favor in a lot of ways. Before the pandemic, they had a run of Fefu and Her Friends at Theatre for a New Audience, and they were going to bring it back this summer. That was exciting. Just the fact that her work is getting done, and getting really stunning, bigger budget productions than she ever got when she was directing her own plays. That’s been really heartening.

Ling: You mentioned you’re working on another documentary. Would you like to plug anything about that before we end?

Memran: I’m working on a film about the Lake Lucille Project, which is in New City, New York, run by Brian Mertes and Melissa Kievman. For 16 years, they’ve been doing one performance of Chekhov every summer. They have five rehearsals, and these people come from all over to be in this acting troupe that rotates. They’ve documented every year, and I’m going through the footage now. It’s another film about the creative process, but it’s about community, why make art at all, and why make theatre at all. Actually, it’s interesting, because Irene’s favorite playwright was Chekhov. It all comes full circle. Hopefully, it doesn’t take me another 20 years to make!

The Rest I Make Up was streamed as part of our 2020 Online International Theatre Festival! Check it out here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.