How does one “write” a life for the stage? This question lies at the heart of Ana Luz Ormazábal’s brilliantly inventive staging of María Isabel, presented as part of Santiago a Mil, Chile’s largest theatre festival and a major showcase for Latin American performance. The play, with dramaturgy by Juan Pablo Troncoso, revolves around the figure of María Isabel Matamala, a doctor and member of MIR, the Revolutionary Left Movement (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionario), a powerful Marxist-Leninist party that Pinochet made it his business to destroy. The piece sets up its playful premise from the start: the four different performers will each play María Isabel Matamala as well as a range of other roles. The decision to commence in the Portuguese language provides an abrupt and entertaining immersion into the ideas of the educator and pedagogue Paulo Freire – who appears in dialogue with Matamala and other colleagues in an early scene. The performer, who reflects to the audience on why she is speaking Portuguese when she is not Brazilian, unsettles ideas around representation and role. Her questions ask where the ethical boundaries of representation lie: who has the right to play a role and why?

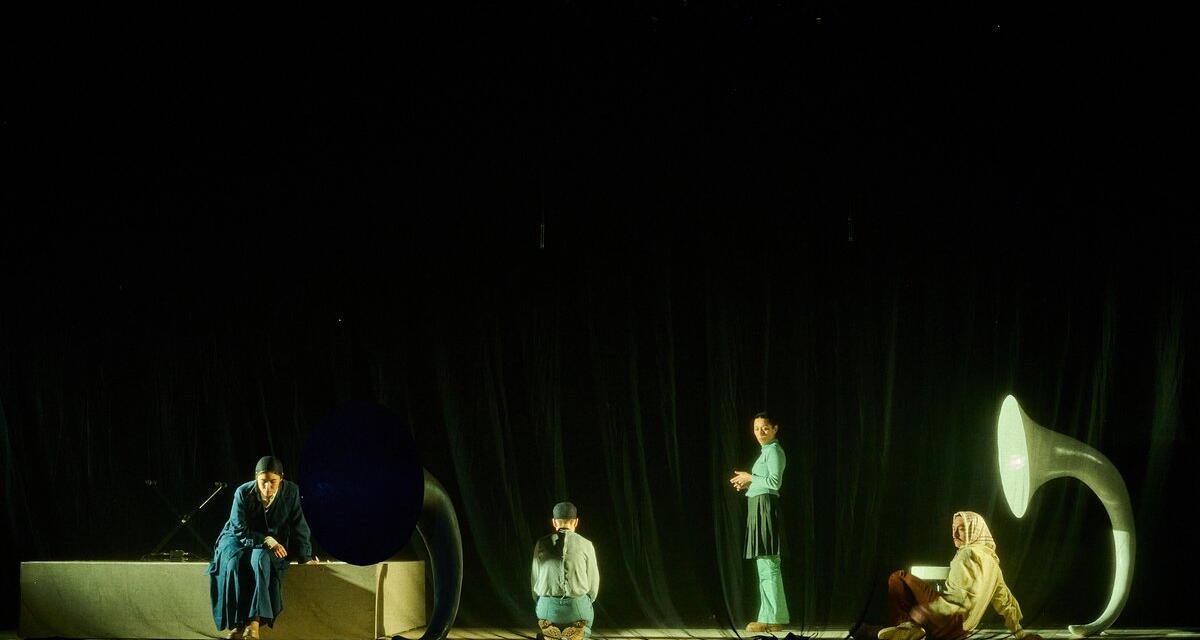

This is an episodic work – scenarios from María Isabel’s life theatricalised in a non-realistic manner over a period between 1970 and 1983 with the four actors — Camila González, Marcela Salinas, Mariela Mignot and Esteban Cerda — taking on multiple roles. The deployment of music and song further accentuates the sense of heightened theatricality. At times, the characters hum softly, almost providing a sonic commentary on the action; at other times the interventions are acute, abrasive and more marked. A keyboard player stage right is almost like a conductor who guides and underscores the action. Three giant white cones — like those on a phonograph — litter the stage, a means through which the characters converse over long distances and an amplifier and modifier of sound. These cones serve like a further percussive instrument for the cast in the crafting of a rich sonic landscape for the production where voice, music and recorded sound intersect. The costumes also eschew realism. Flares from the 70s dominate but the pastel colours – pale green, pale blue — and a combination of beige and rust and denim blue, offer a uniform of sorts for the cast on which they “place” the attire that indicates which character they are playing. Berets position them as political activists; hoods show them as political prisoners in Villa Grimaldi – the notorious torture centre used by the DINA (Pinochet’s secret police) where 4500 were detailed and over 250 were killed; a long-haired wig determines who is playing María Isabel, the actors putting it on in full view of the audience.

This is ingenious, resourceful political theatre. María Isabel uses disguise to avoid capture — taking on a new identity as the elderly Raquel; this metamorphosis is brilliantly enacted as three of the performers cower and take tiny steps — backs stooped and avoiding eye contact, as they scuttle across the stage hoping to remain invisible. In Villa Grimaldi, three actors step tentatively as they walk towards the toilet blindfold, forced to step over the body of a colleague brutally murdered there. The actors become their roles in front of the audience — a process of gestus, in the Brechtian sense, that makes manifest both the construction of role and the construction of history.

The military and secret police are faceless, large white chamber pots serving as helmets that mask their eyes. They may have tried to render their prisoners anonymous, but it is they who are rendered robotic in this nifty production, churning out a script that shows no humanity. DINA architect Miguel Krassnoff Martchenko spits out his anti-Bolshevik credentials facing the audience, hurling abuse towards María Isabel as he interrogates her without ever looking her in the eye. A series of projections on a transparent gauze curtain provide contextual information that grounds the audience in a particular time and space. Joaquín Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez” plays with vocal accompaniment from the actors as María Isabel is tortured. There is no need to show the torture, the vocal disharmony captures the horror of the moment. This is a production that works through suggestion rather than illustration – theatre where nothing is obvious, and the audience is encouraged to imagine and reflect.

It’s not easy to capture the sense of a life dismantled and reconstructed across a difficult political moment, but María Isabel manages it, moving from Villa Grimaldi to Tres Álamos, the prison where María Isabel and colleagues — all acknowledged and named — wrote the feminist manifesto that provided a vision for MIR in the late 70s. The women’s writings are sown into the lining of a burgundy-red coat, transported by a visiting doctor to Paris, only, in a fittingly unromantic manner, it never reaches the intended destination. The manifesto was lost to history. The image of the women in the Tres Álamos prison compound, all writing feverishly under a crisp blanket is pure poetry. Their fingers dance as they scribble at night with the makeshift lights they have fabricated and hold tightly in their hands shining brightly like butterflies fluttering through the air. Indeed, it is poetry rather than prose that prevails in this staging as María Isabel’s pre-recorded recollections and the projections of historical information on the gauze curtain offer a rich contextualisation for the stage action. As the production ends, when María Isabel is released from the Tres Álamos prison and allowed to leave for exile in Stockholm suitcase in hand, she is not alone; three other María Isabels appear with her, walking in unison. Her story is one of many; she is one of many. There is a need to narrate their stories for a new generation. There is no attempt to fetishise or exalt María Isabel, rather the focus is on narrating the tale of an extraordinary woman who went on to renounce MIR but to believe in the need for change, for greater social equity, for justice and parity.

María Isabel eschews exposition; it immerses the audience into a fevered political context where you have to catch up and keep up; it makes for exciting theatre without ever compromising on ethics. There are moments of great humour and a tone that isn’t afraid of showing up the less attractive aspects of the MIR’s ideology without ever opting for easy parody. José Manuel Gatica’s music provides a percussive accompaniment to the action – at times subtle, at times intrusive — and always seamlessly integrated. The four performers, Camila González, Marcela Salinas, Esteban Cerda, and Mariela Mignot, are outstanding — an impressive ensemble. Their bodies contort, weave, intersect and dance across the stage as they capture the different stages in María Isabel’s political journey. In lesser hands this would have been a lehrstück, here it is a deft, magical lesson in political storytelling that had me gripped from start to finish.

Women writing at night: María Isabel at GAM. Photo: Daniel Corvillón

María Isabel runs at GAM as part of Santiago a Mil 2024 on 16 and 17 January 2024.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.