On Saturday 19 November 2022, I witnessed the performance Hands Up! by dancer and choreographer Agnietė Lisičkinaitė whose performance was for the first time shown in a Dutch context at the What You See Festival at Theater Kikker in Utrecht. What You See Festival is a multidisciplinary and international arts festival about gender and identity. The festival celebrated its fifth edition, programming dance, performance, theatre, music, exhibitions, workshops, symposiums, and more. The festival takes place in the city of Utrecht, the fourth largest city of the Netherlands, located in the very centre of the country. In this dance performance, programmed by the festival as a so-called “Dance Action,” Agnietė Lisičkinaitė explores what it entails to protest and researches how protest could take shape. Needless to say, this performance fits perfectly with the festival’s theme “My body, my protest.”

For the start of the performance the audience is taken downstairs where multiple white protest boards of the same size are spread on the floor in the entrance hall. The audience stands close together, covering both the stairs as well as the entrance hall, while listening to a short introduction by the artist. We are told to pick a protest board of our choice, one that resonates with you. You are ought to carry your protest board above your head throughout the whole walk. Agnietė asks us to not respond or talk to anyone, and follow her the whole time. After this short introduction, I find myself, a little bit uncomfortable with the unexpected activity, marching the streets of Utrecht. The texts on the white protest boards are wide-ranging, supporting both sides of the suggested opposites: Yes – No, to give the clearest example. Together with around thirty people, we march the streets. “Trump for president,” “Black Lives Matter,” and even a drawn penis, are raised into the cloudy sky, while the bystanders on the streets come to a halt and watch the happening. If you do not agree with what is on any of the boards, you may raise an empty one. We walk in silence for about fifteen minutes. While marching the streets, I am thinking about this twist: the spectator becoming a performer. Together we perform protest. I am wondering what elements make a protest. How do you perform protest? Is it still a protest if it is performed? If it is not real?

The first protest I attended, was one of the Black Lives Matter Protests, in 2020. My roommate and I heard about the awful news that George Floyd was being killed by a police officer, read about the protests, and decided to go. Due to the Corona virus, we kept our distance. We didn’t march, we didn’t stand close to each other. Without physical touch, I felt so close to everyone present at that time. I raised my board and repeated the words that were shouted. After a few hours, we left the park. I remember getting into a fight with my other roommate about why he wasn’t there. I remember reading about racism, white fragility, Blackness, discrimination, and more, in the first weeks, and ever since. I remember never not seeing my own whiteness anymore. When thinking back on this I ask myself: where lies the power of protest?

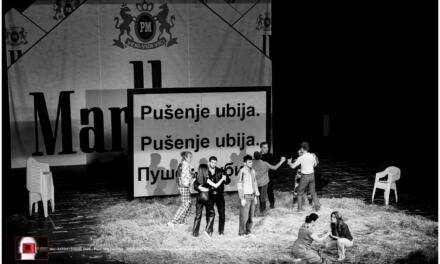

After marching the streets of Utrecht, we enter the theatre, sit down in the audience and watch Agnietė who takes place on stage. The performance continues. Or the performance is about to start: from action to dance. Agnietė who just made everyone part of the performance, turns this around, halfway through. The coming experience she is about to give to the audience is from a whole other level than the first part. She invites the spectator to take place in the audience and takes off her silver high heels and her silver jacket but keeps her silver pants on. On the back wall, film images are projected of the audience marching the streets of Utrecht, just minutes ago. Agnietė moves in front of the projection, the images covering her body. The music is intense. She dances.

The cut from outside to inside is sudden, merciless almost. It could reflect the way protest is, but I wonder whether that is what Agnietė aimed for. Once inside, we are asked to raise our arms, this time without protest boards, and keep them up like this. We copy the movements she makes with her hands. The pain in my arms becomes stronger and stronger, but I don’t want to give up. To speak metaphorically, this is what protesting is. Protesting means dedication. But I realise I probably do not want to disappoint the performer and the people I am with. Though, it does not really matter who I am doing this for, dedication does play a role in this. And that is exactly what the first part lacks for me. The protest boards depicting both sides of the same coin narrow this research down to only the embodiment of protest. The embodiment of one way of protesting. What if I couldn’t raise my arms? Or if I couldn’t walk the streets? What if I didn’t even have a protest board in my hands? To be honest, I didn’t. There were no boards left so I raised my middle fingers a few times.

The performance made me wondering, what is the worth of rehearsing the physical part of a protest when there is nothing we protest for or against? Where is anger or grief, where is the feeling of togetherness I felt so strongly back in 2020, and where is the strength of people working together? What would have happened if we split up, in Yes and No for example, and we would have crossed each other on the streets? What if we protested for one matter, Black lives for example, or only carried the word No. Together. The switch from action to watching leaves me pondering as well. What do those two parts add to the research Agnietė did and how do these two relate to each other? I was surprised, of course, to see myself projected on stage, to see the responses of the bystanders, a lot of them filming us. But there also was silence for me. Not only because we didn’t speak. There was silence through the intense music, slipping through the meaningful message I could see, but I couldn’t feel.

I missed this feeling of standing shoulder to shoulder. I missed the internal and external emotional conflict, the power of being one, the power I feel when answering: “No peace!” to a protest leader shouting “No Justice…” And again, this is also suggesting one way of protesting There are so many ways to not physically be somewhere but still, speak up. Even by being voiceless. And I will not think of silence, I am sure of that. I also missed that a protest does not live within a vacuum. There are preparations on beforehand, or reading and having conversations about it afterwards. Though the performance tickles multiple senses: even when I have left the theatre, I still feel the pain in my arms, I missed that powerful feeling of togetherness and the urgency of speaking up. The optimistic energy rush through my body and the hopeful idea of a possibly changing society.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vera Bonder.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.