Why are stage adaptations of bestselling novels so disappointing? Okay, I appreciate the difficulty of turning a fictional story, which has hundreds of pages to jump back and forth in time, or create wondrously poetic descriptions, into some two and a half hours of stage time. Anyone doing this has to simplify the story, and make it clearer and more direct. Or do they? Lolita Chakrabarti’s Hamnet, her adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 hit for the Royal Shakespeare Company, now arrives in the West End and will interest many of the book’s fans, but is it a good play?

O’Farrell’s novel is a sophisticated, highly literary account of one of the most well-known gaps in cultural history — namely Shakespeare’s wife. Traditionally known as Anne Hathaway, she married William in 1582, when she was 26 years old and already pregnant, and he was 18. They had three children, Susanna, and then the twins Hamnet and Judith. She outlived her husband by seven years. Practically nothing else is known about her life, an absence of information which is a godsend to novelists, enabling O’Farrell — as well as other writers before her — to fully imagine the bard’s family life.

Now named Agnes Hathaway, Chakrabarti introduces her as an independent strong-minded woman, who is equally at home with managing a kestrel and cooking up herbal remedies. Attracted to the teenage William, whose glove-making and drink-loving father John and mother Mary are also pictured in rather fraught circumstances, Agnes finds love with this well-educated, but impoverished boy. The couple marry, are happy for a while, have their kids, then William goes to London to sell gloves, falls in with theatre people, and the rest is, as they say, history.

Erica Whyman’s production, her farewell after a decade with the RSC, starts slowly in the domestic tensions of the Shakespeare household, with some welcome conflict also coming from the relationship between Agnes and her stepmother Joan. Agnes is more down-to-earth here than in the novel, but her quality of otherness, of being a seer, given to terrifying visions of her future, and the gossip that she is a witch, are all demonstrated. The deep connection between the twins Hamnet and Judith is also sketched in, but it is only in its second half that the play finds some emotional depth.

This is when bubonic plague visits Stratford-on-Avon, and both twins fall ill. But while the girl recovers, Hamnet dies — and he was only 11. William Shakespeare, now an actor and playwright in far-off London, arrives too late and helplessly watches the grief and guilt of his wife and other children. But his mind is elsewhere, and soon we watch him rehearsing The Comedy of Errors with fellow entertainers Richard Burbage and Will Kempe, and deciding to split the history play Henry IV into two parts. These scenes are so perfunctory that you can’t help wishing you were watching Shakespeare in Love.

Chakrabarti does a good job in reminding us that genius playwrights had a home life, where women’s experiences of pregnancy and childbirth had a shared power and often dramatic consequences, and her Agnes embraces nature and natural healing with conviction if not with poetry. The menstruation and birth scenes have a feminist integrity, but the complexity of the extended family relationships does diffuse some of the dramatic conflicts. It’s only at the very end of the play, with William’s use of the story of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, and its echo of his dead son’s name, that we get a distinct pulse of emotional pain.

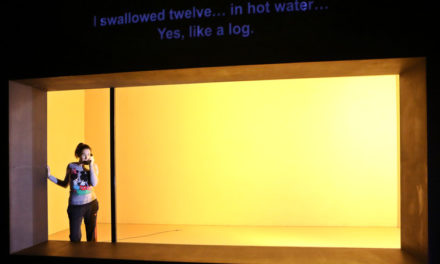

The moments when Ajani Cabey, the actor playing Hamnet, also performs Hamlet’s speeches, however briefly, are very moving, and Shakespeare’s poetry fills some of the gaps left by excluding O’Farrell’s imaginative writing. The key messages of the story, that writers often refer to their experiences of home and that genius in not an individual quality but is based on a creative interaction with immediate family, come across clearly. Shakespeare’s interest in reuniting separated twins and his ability to express suicidal grief both make greater sense after witnessing Hamnet. But what is missing is a linguistically interesting reimagination of the story.

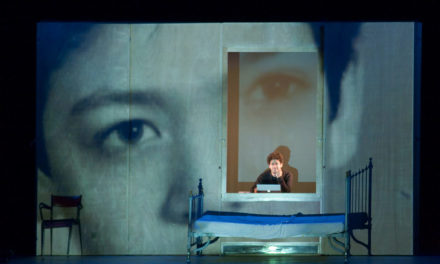

So although much of the evening is pedestrian, it does have its moments of acute pleasure. Whyman’s directing, on Tom Piper’s wooden set which conjures up rural Warwickshire and London playhouses alike, brings out some good performances: Madeleine Mantock’s Agnes and Tom Varey’s are especially good in the early scenes, although her journey from confident self-possession to grief-stricken motherhood is more convincing that his from callow youth to successful playwright. Cabey and Alex Jarrett give Hamnet and Judith an energetic stage presence, while Sarah Belcher’s Joan and Gabriel Akuwudike as Agnes’s brother lend solid support. What is disappointing, however, is that this stage version has not found a voice of its very own.

Hamnet is at the Garrick Theatre until 17 February 2024.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.