As part of the Asian Theatremakers series

Liu Xiaoyi and I are arranging for a time and date to meet for this interview. He texts me the options:

7th morning 11am

8th morning 1030am

8th late afternoon 448pm

Liu Xiaoyi

His latest work for the 2019 Huayi – Chinese Festival of Arts is inspired by the late British playwright Sarah Kane’s final play, 4.48 Psychosis. I’m almost tempted to run with the wry dig–the founder and artistic director of experimental theatre group Emergency Stairs has a gleeful penchant for puns, wordplay and inside jokes. But I’m on a tight deadline and I pick the morning of the 7th.

“Careful!” he gestures to a line of string running across the entrance of his company’s 62sqm space in the Soon Wing Industrial Building along Macpherson Road. It’s about the size of a three-room HDB flat. One of the walls is lined with dark, jagged, almost abstract expressionist charcoal sketches. He’s written cryptic poetry on the windows that open out to the rest of the industrial estate. There’s string twined round the one table and two chairs in the center of the boxy space, physical echoes of Emergency Stairs’ annual intercultural festival, Southernmost: One Table Two Chairs Project. [1]

He surveys the room, “For the past two weeks I’ve been spending 448 minutes here, alone, every day.”

Charcoal sketches on the walls of the space that Emergency Stairs occupies.

Xiaoyi has just emerged from an intense two-week workshop phase for FOUR FOUR EIGHT. Sound designer Darren Ng and lighting designer Lim Woan Wen, who are working with him on the show, have been giving him daily tasks to complete within those 448 minutes (about 7½ hours).

He gestures to the drawing, “They asked me to draw my fears, my secrets, my beauty, my soul, my ugliness…Sometimes they would send me music to listen to, in the darkness.”

Another task involved walking from Emergency Stairs back to his home over the course of three hours in the blazing heat.

“And my house is not that far from here,” he says, “so I had to walk veeerrry slowly.”

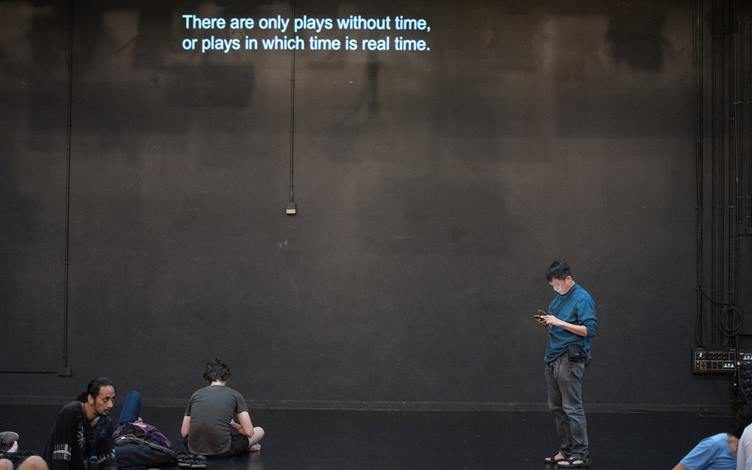

Time

Time stretches and collapses in Xiaoyi’s work. It demands that audience members walk their own paths in the thick, dense labyrinths of performance. FOUR FOUR EIGHT will last 5½ hours (audience members are free to come and go as they please); his previous two pieces at Huayi, Offending The Audience (2017) and Einstein In The Carpark (2018) ran for 1½ hours each but felt substantially longer, largely because of how the audience experience is scaffolded.

His productions are equal parts frustrating and fascinating. The audience often has to make their own map of the work from a handful of opaque and oblique clues–perhaps a tongue-in-cheek director’s message in the program booklet arranged as a series of questions or a glossary, or a glimpse of the work’s direction in an open rehearsal.

Xiaoyi tends to use a performance score instead of a script, timing every emerging and fading image and interaction down to the minute, and sometimes to the second.

Within these strict rhythmic structures is also room for the performer to improvise and respond to their environment and spectators. He revels in slow, careful movement and almost cinematic freeze frames, arranging and sculpting the performers both on stage and off stage.

During rehearsals for the 2018 Southernmost festival, he told the featured artists that he preferred slow movements to a rapid, virtuosic display of the performer’s abilities,

“You need to leave space for an active audience. If you pause and slow down, if you stop, they see you, and not just your technique.”

Each of the productions in the Huayi trilogy has taken a significant post-dramatic work from the 1960s to 1990s as a leaping off point, and while they are strange new creatures in their own right, it’s often tempting to call Xiaoyi’s pieces radical reworkings, reinterpretations or responses to Peter Handke’s Offending The Audience (1966), Robert Wilson and Philip Glass’ Einstein On The Beach (1976), and Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis (1999-2000).

Xiaoyi’s fascination with post-dramatic theatre has also seen him toying with when a piece begins and ends, and what constitutes engagement with a work such that it doesn’t only occupy a specific moment in time or history:

“When the audience members are watching a show, they are actually experiencing a process. I just think if we can take a step backwards (or forwards), inviting the audience to observe the rehearsals is just an extension of a process. If we see the performance of Southernmost as the curtain call of the bigger/longer performance, then it makes a lot of sense for the audience to watch the performance before the curtain call. So they might understand and appreciate the curtain call in a different way.” [2]

Theorist Sarah Bay-Cheng argues that performance is a mode rather than a discrete event; a performance may begin from the moment you search for it on the internet, or one might be “haunted by the memories, recycling, and ghosting of performances past.” [3]

As part of FOUR FOUR EIGHT, for instance, the audience is invited to correspond with Xiaoyi over email in the weeks before the physical performance.

One might see Emergency Stairs itself as a durational performance.

“The plan for the next few years is to search for an alternative way to…” Xiaoyi pauses, “uh… should I say ‘survive’? ‘Survive’ is so passive. I see Emergency Stairs as a project, as an experiment. If the theatre company is also one of my projects, then how am I going to deal with it not just within Singapore’s linear model? Are there any other ways to do it?”

The heart of Emergency Stairs isn’t just the performances and projects it creates, but how the company interacts with its environment: partners, patrons, audience members, policymakers, government.

At the 2018 Southernmost festival, its cornerstone production Journey To Nowhere responded to and critiqued the SG Arts Plan 2018-2022 unveiled by the National Arts Council. Xiaoyi said of this,

“I guess this is the script that has been given to me. And this script has a duration of five years. How can I respond to this script? How can I negotiate with it and challenge it? […] Who takes initiative? How can we empower ourselves? I think that’s why I see One Table Two Chairs as a project, not just a production. I’m looking for any alternative ways of art-making. Right now, I’m following the script. But can I write the script in another language, on another piece of paper?” [4]

LANGUAGE AND VOCABULARY

Xiaoyi arrived in Singapore from his hometown of Jieyang in the 1990s as a teenager. He first attended Anglican High School, then studied electronic engineering at a local polytechnic, then majored in Chinese Studies at university. During a speech at the Intercultural Theatre Institute in 2018, he spoke about the perpetual dialogue between the various languages that inhabit his body: Teochew (his mother tongue), Mandarin Chinese, Hokkien, Cantonese, and English:

“When I was 16, I moved to Singapore by myself. The irony was, the first language I had to learn after arriving in Singapore was not English, but Chinese Mandarin. I still remember, when I first came to Singapore and joined a storytelling competition in my secondary school. My teacher commented, ‘What’s the matter with your Chinese? It’s even worse than Singaporeans.’ To this day, I have stayed in Singapore for almost 20 years. Now I am proficient in both Chinese Mandarin and Singlish. I can understand Hokkien and Cantonese well. And although it’s difficult for me, in this moment, I’m trying my best to deliver this speech in English.” [5]

He also enjoyed picking up various programming languages when he worked in an IT company, but soon grew bored of having conversations with machines. In 2001, at the age of 19, he began performing with The Theatre Practice after an audition notice in the newspaper caught his eye.

These days, he often refers to various motifs and items in his productions as “vocabulary”, and talks about “adding” vocabulary to his work. This vocabulary could be a prop (a piece of paper, or a blindfold), a sound (a performer counting out loud, or the ripple of a drum), or a gesture repeated throughout the piece. This isn’t a secret language by any means, but it’s often invisible to the public who come to see the “final product,” and the company has been looking at ways to make the processual part of their work more accessible to their audience.

Each of Xiaoyi’s productions may have its own language and vocabulary, but he also frames his projects as conversations between bodies and art forms and systems. He counts as two of his major artistic influences Danny Yung, the co-artistic director of Zuni Icosahedron (Hong Kong) and Makoto Sato, the artistic director of Za-Koenji Public Theatre (Tokyo), both of whom were instrumental in shaping his performance-making ethos, and his ongoing relationship with traditional forms and innovative structures.

The Southernmost festival is one of his main platforms for dialogue, where he invites artists from what we often refer to as “traditional” art forms across Asia (e.g. Kun opera, Noh theatre, lakhaon khaol, Chinese dance, Malay dance, etc.) to rehearse, perform and connect with each other across cultures and languages.

SPACES, BOUNDARIES, AND BORDERS

Xiaoyi also has a deep affection for long conversations with unexpected spaces. During his time with The Theatre Practice, where he helmed the company’s experimental arm The Practice Lab, he staged 11 • Kuo Pao Kun Devised (2012), an homage to the late dramatist Kuo that framed beautiful and fleeting images in and around the Stamford Arts Centre, the company’s former premises. Audience members might be positioned on the roof to watch a small moment unfurl on the ground below. In Uproot (2016), Xiaoyi’s final production with The Theatre Practice, he had the audience sit in darkness, watching vehicle headlights approach and vanish through the windows.

The interrogation of these spaces and boundaries comes from Xiaoyi’s own journey from performer to director to founder of a company:

“I started off as an actor, and as an actor, you’re very sensitive to the boundaries of your body. You know the boundaries of the stage–where the backstage is, what the audience sees of you. When I became a director, I stepped off the stage. I started to get to know the bigger picture. You see the four walls of the theatre space, the exits and entry points. I also started to meet other boundaries, like what the budget is, and what my resources are. And then when I started Emergency Stairs–it’s an even bigger picture. My boundaries are so different now. I know more about the NAC (National Arts Council), the IMDA (Info-communications Media Development Authority; also a regulatory board), about arts housing, about cultural policy… And I thought, how can deal with all of this creatively?” [6]

His conversation with space also extends to the institutions and systems behind a space. He sees his Huayi trilogy (2017-2019), for instance, as a conversation with Esplanade–Theatres on the Bay as an institution and what he can provoke and prod within it. He explains that Offending The Audience was about opening up the theatre space,

“The audience has the freedom to walk around the space, to go out and come back, to lie down on the floor, to do whatever they want in the space–that’s the first step.”

Offending the Audience

The following year, for Einstein In The Carpark, “I opened up the structure of time. The audience has to deal with their own time. It’s like backpacking on your own versus following a tour guide.”

This year, FOUR FOUR EIGHT will be staged in a whiskey bar at Esplanade Mall. The amount of freedom bestowed on the audience is simultaneously liberating and alienating. Halfway through my experience of Einstein In The Carpark, I observed that half the audience was attempting to follow the performers around the vast subterranean space, and the other half was sitting in the air-conditioned lift lobby, fanning themselves and looking at their phones. [7]

“Some people say that Emergency Stairs is not radical enough in the [Singapore theatre] scene. And I would say yes. We are not enough,” he says, “I think in order to challenge the structure or push the boundaries, we have to understand where the boundaries are and the structure is before we try to push. I think in Singapore the structure is so stable and so hard to push. I need to keep negotiating with the presenter, and also the audience.”

- Einstein In The Carpark featured Kun Opera performer Zhang Jun and musical actor George Chan at Huayi 2018.

- The production encouraged audiences to roam freely in Esplanade’s B2 carpark.

RETREAT / ENTREAT

In the late 2000s, Xiaoyi and his wife took a holiday to Yunnan, where they visited the city of Dali. They fell in love with the city, ringed by mountains and sky, and set themselves a deadline–they would relocate to the city and stay there for a year or two. They had no idea what they would do or how they would make a living, but they knew,

“we die die have to leave Singapore and go to Dali… We sold everything, or gave things to friends, or threw them away, and we went with two big backpacks.”

Eventually, they rented a two-story house and turned it into a cozy bed and breakfast. They named the place 退避一舍 (tui bi yi she), a pun on the Chinese idiom 退避三舍 (tui bi san she), which literally means to retreat three day’s march, i.e. to make a strategic retreat in the face of superior strength.

He says, “It was so fruitful. Because you open your house and you let people come in. They stay in your house, and then they share their stories with you. Sometimes they’d cook, or I would cook for them. It’s like I provided a platform for people to exchange.”

This invitation to share time and space beyond the event of a performance, to invite audience members to make their own abode in a work, no matter how challenging or strange, is one of the productive tensions of Xiaoyi’s work. He invites the spectator to be both nomadic and communal, to be a sort of co-collaborator with him in the process of decoding a work. The same goes for the performers he invites to work with him.

He grins, “I always told the cast of 11 • Kuo Pao Kun Devised, I am not the director. I am more like the editor of a magazine. I open my book and invite you to write something down.”

As critic-in-residence at the 2018 Southernmost festival, I observed how hospitable he was with his collaborators, inviting everyone to share meals, to learn each other’s languages.

He could move between unobtrusive, fly-on-the-wall invisibility and quiet, precise direction in an instant, absorbing every improvisation and interaction and filing it away in the larger roadmap of his mind.

Emergency Stairs has turned out to be a kind of retreat for both performance-makers and theatre-goers. Its name evokes escape, safety, movement, functionality, and urgency; it is a retreat as much as it is also an entreaty to audiences and artists to both establish and demolish notions of time and space in “the theatre,” to interrogate what a performance actually means to them.

Xiaoyi is wearing one of his signature black T-shirts today–this one has a small white question mark across his chest. His theatrical conscience perhaps, the small voice in the back of his mind always asking questions, never satisfied with easy answers.

[2] Gwen Pew. (2018). “Interview with Liu Xiaoyi” for Centre 42. Retrieved from http://centre42.sg/interview-with-liu-xiaoyi/

[3] Sarah Bay-Cheng. (2012). “Theater is Media: Some Principles for a Digital Historiography of Performance” in Theater, 42:2, p. 33. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274350846_Theater_Is_Media_Some_Principles_for_a_Digital_Historiography_of_Performance

[4] Corrie Tan. (2018). “Day 3 (Nov 6) – conversations; coming together” for Southernmost 2018. Retrieved from https://southernmost2018.wordpress.com/2018/11/08/day-3-conversations-coming-together/

[5] Liu Xiaoyi. (2018). “From Individual Reflection to Intercultural Dialogue” presented at the 2018 ITI Theatre Forum.

[6] Corrie Tan. (2018). “Day 3 (Nov 6) – conversations; coming together” for Southernmost 2018. Retrieved from https://southernmost2018.wordpress.com/2018/11/08/day-3-conversations-coming-together/

[7] Corrie Tan. (2018). “Life isn’t a beach in Einstein in the Carpark”, Arts Equator. Retrieved from https://artsequator.com/einstein-in-the-carpark-review/

This article originally published by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay, Singapore on January 22, 2019, at www.esplanade.com/learn. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Corrie Tan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.