The University of Western Ontario’s Arts and Humanities Student Council (AHSC) recently staged its latest production The Interrogation of Baruch de Spinoza written by David Ives. The play was performed at TAP Centre for Creativity at London, Ontario, Canada from January 30th to February 2nd and was directed by Julia Sebastien.

The play focuses on one episode in the life of the famous 17th century Dutch Philosopher Baruch de Spinoza. The episode entails the notorious trial he underwent that finally led to his exile from Amsterdam and expulsion from the Jewish community he belonged. The reason for his trial was simple and is even relevant today: he believed in rationality and spoke against the sacred Jewish texts. The central question that the play asks is this—should one choose to belong by giving in to the emotion, or should one choose to be exiled by listening to reason? This question forms the spine of the play, and we see a very vulnerable but equally rational Baruch Spinoza swaying from one end to the other, at times confused and hurt by the acts of his friend, his lover, and his teacher, and at times extremely stubborn in his views on religion, God and Philosophy.

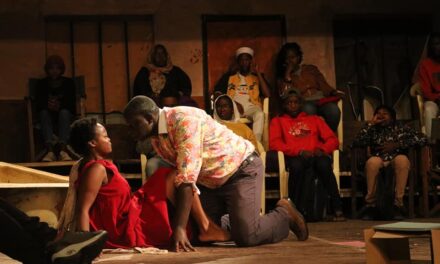

The play uses minimal set, introductory music, and simple light design, and depends heavily on the actors to capture the mood, the setting and the layers of the play. We see a direct address to the audience, we also see an actor speaking from the arena of the audience and going to the arena of the performers. Traditionally critics call it the “breaking of the fourth wall.” However, what the director Julia Sebastien does here is much more complex and nuanced: there is no breaking of any walls. The audience is already a part of the trial right from the word “go.” This strips away the agency from the audience who is forced to get out of its comfort zone to think about the difficult theological and philosophical questions that the play poses.

The play takes time to pick up. The first half almost seems like a preface to the emotionally moving and intellectually challenging moments that are to follow in the second half. The actors have not exactly settled in the skin of the character, the conflict has not reached its pinnacle and the emotional stakes are not as high in the first half. The larger stage presence of Baruch Spinoza’s sister Rebekah and his teacher Rabbi Saul Mortera in the second half brings in the much-needed energy and complexity to the play. Credit should be given to Emily Tennenhouse, for portraying the irritable, whiny character of Rebekah Spinoza so convincingly. However, Rabbi Mortera’s character played by the brilliant Kevin Heslop deserves a special mention. Heslop not only manages to capture all the complex layers of emotions that Rabbi Mortera feels while putting his favorite pupil on trial but also captures the complicated history he shares with Baruch Spinoza. It is in the highly moving moments between Baruch Spinoza and Rabbi Mortera that the play reaches its emotional maturity, and it is Rabbi Mortera’s final “Amen” spoken in a trembling, melancholic voice that echoes in the minds of the audience long after the final candle is blown off.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abhimanyu Acharya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.