Anton Chekhov: Life is life, that’s all there is to it

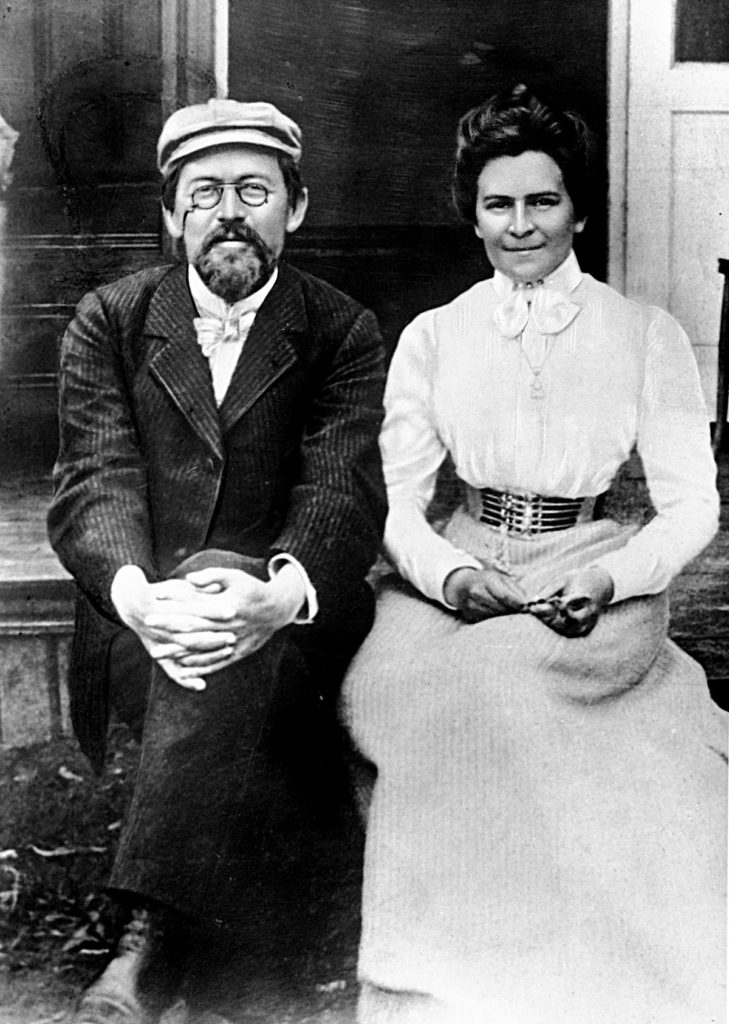

Russian writer Anton Chekhov and his wife, actress Olga Knipper-Chekhova

Sputnik

Shortly before he died, Chekhov wrote to his wife Olga Knipper: “You ask what life is. It’s like asking what a carrot is. A carrot is a carrot, that’s all there is to it.”

He stated that life is essentially what the individual perceives it to be, inviting the question: What if there is no higher idea justifying human existence?

Chekhov believed that “if there is meaning and purpose in life, then this meaning and purpose is not to be found in our happiness, but in something greater and more rational.”

The writer asserted that happy people are blissfully ignorant of other people’s woes. He opined that “at the door of every happy man someone should stand with a little hammer, constantly tapping, to remind him that unhappy people exist.” This “constant tapping at the door” sounds eerily like Facebook (although whether it opens people’s eyes to the misfortunate of others is debatable).

Fyodor Dostoevsky: People are not always what they say aloud

Nikolai Stavrogin. A screenshot from Vladimir Khotinenko’s series Demons. Vladimir Khotinenko/Non-Stop Production, 2014/Sputnik

The modern person gets bombarded with information online, which they often spice up before sharing. But that doesn’t mean that the sharers agree with it. Creating an effect is more important.

The protagonist of Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov says:

“Man is broad, too broad, I’d have him narrower.”

He is amazed at how conflicting thoughts can coexist inside one person.

An example of such a contradiction is found in the novel Demons. Stavrogin, in dialogue with Shatov, admits to being an atheist. Shatov tries to expose his adversary as untruthful. He recalls Stavrogin’s phrases two years previously that the Russians are a “God-bearing people” and that “an atheist immediately ceases to be Russian.”

“Didn’t you tell me,” shouts Shatov at Stavrogin, “that if it were proved to you mathematically that the truth lies outside of Christ, you would prefer to remain with Christ rather than the truth?”

Incidentally, this phrase about Christ is contained in the letters of Dostoevsky himself.

Leo Tolstoy: Everything is in vain, happiness is in simplicity

Bolkonsky (in the foreground) and Napoleon after the Austerlitz battle. A screenshot from Sergei Bondarchuk’s film War And Peace

Sputnik

In his novels, Tolstoy intentionally departs from the here and now—all that is momentary is mortal and worthless.

At the heart of his worldview are morality and virtue, and any civilizational development, in Tolstoy’s mind’s eye, only degrades humanity: people have sex not only to reproduce, they don’t wear clothes merely to keep warm. The writer wanted to remove his characters from the usual circle and return them to a natural, simple state.

Andrei Bolkonsky in War and Peace is wounded in battle and finds himself in the (for him) unusual position of lying on the ground face up. He gazes at the sky, amazed that he has never before noticed this blue vastness. And he is happy to have done so at last. He starts to wonder why they are fighting the French, why all the charging and screaming, what’s it all for?!

“Everything is empty, everything is deceit, except this endless sky.”

In Anna Karenina, the wife of the brother of the title character accuses her husband of infidelity and shows him a note as proof. But the philandering husband is tormented not by what has happened, but by his reaction to it.

“There happened to him at that instant what happens to people when they are unexpectedly caught in something very disgraceful. He did not succeed in adapting his face to the position in which he was placed towards his wife by the discovery of his fault. Instead of being hurt, denying, defending himself, begging forgiveness, instead of remaining indifferent even—anything would have been better than what he did do—his face utterly involuntarily assumed its habitual, good-humored, and therefore idiotic smile.”

Among all the conventions of society, among all the innovations and constant changes, Tolstoy seems to ask us: where, oh where is the real person?

Russia Beyond is grateful to Dmitry Bak and the Live Talk project for their assistance in preparing this material.

This article originally appeared in Russia Beyond on October 7, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexandra Guzeva - Russia Beyond the Headlines.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.