The death of Yury Lyubimov in Moscow on Sunday morning, October 5, 2014, at the age of 97, puts “paid” to an enormous number of accounts in Russian theater history. Forget “theater” history – in Russian history, plain and simple.

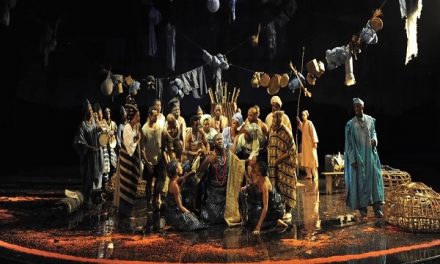

For a man who didn’t really begin his life as a director until he was 46, he had an astonishingly fruitful career. Between 1964, when he founded what would become the world-famous Taganka Theater with Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person of Setzuan, until 2013, when he staged Alexander Borodin’s opera Prince Igor at the Bolshoi Theater, Lyubimov directed 117 shows. Add one more for his first show, staged at the Vakhtangov Theater in 1959, Alexander Galich’s Does a Man Need Much?

Lyubimov was a horn of plenty, overflowing with energy, work, controversy, opinion, intrigue and accomplishments for the better part of a century. We will be making sense of everything he touched, created and influenced for years and decades to come.

Lyubimov was a master director. As I wrote earlier today in a piece for The Moscow Times, two hands aren’t enough on which to count the Lyubimov productions that changed Russian theater history. An abbreviated list begins with The Good Person of Setzuan and continues with John Reed’s Ten Days That Shook the World (1965), Listen! (1967) after the poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky, Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1971), Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (1976), Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1979), Yury Trifonov’s The House on the Embankment (1980), and Alexander Pushkin’s Boris Godunov (1982, revived in 1988).

When Lyubimov was stripped of his Soviet citizenship in 1984, he gained world renown in ways theater directors rarely do. That notoriety was backed by quality work. The Taganka prompted Arthur Miller to say that his faith in theater had been renewed. Even before the enforced break with the Taganka and Russia, Lyubimov staged hugely successful operas at numerous opera houses in Italy, not the least of which was La Scala in Milan. Newspapers the world over responded when Lyubimov returned to Moscow and the Taganka in 1989.

The facts; you can stack them until you’re blue in the face, and you still won’t come close to putting in everything that needs to be there. And what I want to do is to come up with a personal picture of a man that history fated me to live alongside for over a quarter of a century. I’m not after something sentimental with lots of pastels. I want something real that does not avoid the darkness that was an element of every production Lyubimov ever created.

I first met Lyubimov at a touchy moment. It was the spring of 1987 and he was in Cambridge to restage his famous Bulgakov dramatization, The Master and Margarita at the American Repertory Theater. I was, at the time, a grad student at Harvard in the Slavic Department, preparing to write a dissertation about the playwright, Nikolai Erdman. Knowing Lyubimov and Erdman had been close for decades, I arranged, through exiled Soviet novelist Vasily Aksyonov, to meet with Lyubimov to talk about his friend.

What I didn’t know beyond a few vague rumblings is that something had gone haywire at ART. Lyubimov was furious with the theater and Robert Brustein was livid with Lyubimov. I showed up on the doorstep of Lyubimov’s rented apartment in Cambridge just as that meltdown, not quite yet public, was peaking.

Lyubimov, who did not speak English, felt isolated in Cambridge. He had no one to talk to, no press to perform for. And, by now, he had become a past master at playing controversy into extra-curricular theatrics. His battles with the Soviet authorities over two decades, and his handling of the press in 1984 when he was stripped of his citizenship in London, had honed his talent and his appetite for verbal gymnastics.

In short, I walked into a hornet’s nest. Lyubimov began our chat by unloading a barrage at Brustein and the ART. I wasn’t sure what I was hearing at first, but it didn’t take long for me to put two and two together. The Master and Margarita, which I was dying to see as a subscriber to the ART, was not going to happen. And Lyubimov wanted to talk about it. I was too dumbfounded and too fascinated to remind my host that I was there to talk about Nikolai Erdman.

Now it is crucial to this story to point out that Lyubimov and his young Hungarian wife Katalin were as gracious as they could be. I was received in their home with tremendous warmth and kindness. Lyubimov made sure Katalin had a cup of tea and a plate of cookies in front of me almost before I sat down. Lyubimov’s extraordinarily charming, even impish, smile, something that remained with him to the end of his life, shined on me like a sun. I could not pull my eyes off the spectacle of his graceful, gentle hands, which I would see him employ many years later with devastating success when he came out of retirement as an actor and played Joseph Stalin in his own production of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gang of Swindlers at the Taganka in 1998.

I had not yet warmed my seat and I felt as though I had been accepted as an honored guest, if not a family member, into the Lyubimov household. Katalin went off to walk with their toddler son, and I settled in, happily anticipating a wonderful chat about Nikolai Erdman. Then it began – the harrowing story of the break with the ART.

These details are necessary to make the following point: I was initiated into the extremes of the extraordinary world of Yury Lyubimov in a matter of minutes. From kindness to killer instinct in 30 seconds flat. This was an education with a capital E. It’s the kind that comes only when you don’t expect it and you don’t yet know what to do with it. It was my first encounter with an individual who comfortably lived a life that was bigger than life. This was a man for whom history was home. And he was entirely at ease there.

Fate, once again doing what it does, put me in Moscow when Lyubimov returned to the Taganka Theater during the 1988/89 season. Thus I had the opportunity to continue observing him at relatively short distance. I sat in on rehearsals when he restaged his majestic production of Boris Godunov. I sat in on a table reading of Erdman’s The Suicide in the upstairs foyer of the Taganka. This would have been sometime in 1990. It was only nominally a rehearsal, for Lyubimov, who always loved an audience, used it as an opportunity to pontificate on his life, Erdman’s life, Soviet history, the story of the Taganka, his young son’s funny habits, the crimes of the Communist Party, and his own personal beef with certain actors.

He could be quite insulting to actors. I know many of his actors, past and present, who will never forgive him for his harsh tongue. The final conflict between Lyubimov and his troupe in 2011, which ended with the director walking out of the theater he created, was one I had seen coming for twenty years.

I was there to watch the second honeymoon between Lyubimov and his company shatter like glass in 1992. Actors were furious with what they perceived to be their director’s imperious behavior. I interviewed Lyubimov again as, in 1993, he fought his former lead actor Nikolai Gubenko in the continuation of the civil war that finally broke the Taganka into two separate entities. I remember the accusations that Lyubimov had abandoned his theater again in the mid-1990s, while he mounted a whole series of shows in Germany, Greece, and Finland.

I occasionally attended the seemingly unending stream of press conferences that Lyubimov would call in order to make his position known on these and other pressing issues facing the Taganka.

Perhaps more than anything of this sort, I recall attending an anniversary celebration at the Taganka. I believe it was the 40th in 2004. Throughout the evening foreign guests and dignitaries came on stage, gave speeches and delivered gifts and bouquets. It was as though the actors of the Taganka itself – and there were still plenty there who had been with Lyubimov in the 1960s or the 1970s – did not exist. As the celebration reached its culmination Alla Demidova, one of Lyubimov’s leading actresses from 1964 through the early 1990s, took up a modest position at the corner of the stage, virtually unnoticed by anyone, Lyubimov included. Just then someone told Lyubimov that an actress he worked once with in Greece was in the hall. Making much of the news he called the actress on stage, embraced her, forced flowers into her hands, and praised her highly, then pushed her forward to receive the thunderous applause from the packed house.

Demidova, an icon of her era, stood 15 feet away with a carefully controlled, expressionless look on her face. She did not make a move, remaining on stage until everyone left together.

Now, let me point out the following for those who may misunderstand me. I am not casting stones. I am attempting to paint, if not a portrait, then at least a sketch of a complex man who was a great artist. Lyubimov possessed all the human virtues and vices in exaggerated form and amounts. He could spend the last 34 years of his life restating the love and respect he held for his great actor, his great Hamlet, Vladimir Vysotsky. And he could publicly ignore Hamlet’s Gertrude, standing just steps away.

But you’ll remember what I said earlier about epiphanies and educating moments. Demidova, when Lyubimov died on Sunday, provided another of those. Writing on the blog page of the popular Moscow radio station Echo Moskvy, she offered up a few brief sentences steeped with nothing but love, respect and understanding.

“When a genius passes,” Demidova wrote, “it is a great loss for an entire era, not only for family and for those who worked with him. The Taganka, Lyubimov – this page will be studied, dissertations will be written, books will be written, because in the 1960s he turned theater in a completely new theatrical direction. It was a time of dead, academic form. All theaters looked alike. And suddenly there was this festive explosion at the Taganka. There was always something new. There are directors who find themselves. And then they take this discovery, this directorial gesture, and they use it their entire life. Although you can always recognize Lyubimov by any mise en scene in a show, every time was always a discovery. Because for him time was always what was important, and time changes every day. […] The Taganka is now being renovated. I would now name the Taganka not the Taganka, but the Yury Lyubimov Theater. He deserves that.”

Sometimes before premieres at the Taganka I would join a few other invited guests for tea and cookies with Lyubimov in his office. It always reminded me of our very first meeting. Lyubimov would hold court, as he did with me that day in 1987, reviling the gathered masses with barbed stories and great memories.

From the office upstairs we would go down to the foyer where Lyubimov, bestowing his radiant smile on everyone in attendance, welcomed all to his theater as they showered his appearance and his final introductory words with ovations. The doors to the auditorium would swing open, we would fill the hall to the brim, and Lyubimov would take his traditional seat at a desk with a green lamp, a script, and a weak flashlight that he would shake at the actors when he felt the tempo of their performance was flagging.

Yury Lyubimov was so much more than anything I can tell. His world was so big you could only see small parts of it at any one time. This is a man who was born a week before the Russian Revolution took place. He shook Meyerhold’s hand when he was a student at the Shchukin Institute. He claimed he once nearly killed Boris Pasternak, when a piece of the dagger, with which Lyubimov-Romeo killed Tybalt, flew into the hall at the Vakhtangov Theater and embedded itself in the chair by Pasternak’s shoulder. This is a man who stood up to the KGB and the Communist Party when they attacked his art at the Taganka. But he was also a man who maintained a relationship with Yury Andropov, the head of the KGB from 1967 to 1982, and the General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1982 to 1984.

Lyubimov was a man of great contrasts, great instincts, tremendous insight and prodigious talent. He lived for theater. He was a walking theater in and of himself. He turned even the simplest of human exchanges into theatrical performances. He loved a controversy, he never feared a scandal. If it cost him a friend or two along the way, so be it. To him, it was all theater. It was something to be played, something to be given form and enhanced meaning.

Yury Lyubimov had a way of imparting great meaning to everything he said or did. He knew better than anyone how hard it is to make good – no, great – theater. The kind of theater that rewrites history. As Alla Demidova suggested, the history books will have plenty to say about Lyubimov’s art. They will debate it, interpret it, misinterpret it, and came back around to it for another look another time. That process begins today.

What ends today for me is that period in my life when I, an interested, a fascinated, observer, cease to walk alongside Yury Lyubimov. It was a dumb stroke of fate that occasionally put me in that position. And to that dumb stroke of fate, I feel a deep, agitating sense of gratitude.

I learned some valuable lessons from Lyubimov. I learned that an artist is the world unto him or herself, and that you judge them only on their own terms. I learned that theater and fairness have nothing to do with one another. I learned that talk and deed may wound, but art can heal. I learned that beauty is enhanced by clumsiness and flaws.

Yury Lyubimov is gone. Pardon the cliche after all these words, but an era has ended. It’s no less true because people are saying that all over the world today.

P.S. As briefly as possible, one lesson I obviously didn’t learn well enough.

That day in 1987 Lyubimov was so kind and so welcoming that it never occurred to me I might be an imposition. Finally, after more than two hours had passed, he stopped and in his gentle voice said, “Oh, we talk so much. We talk and talk and talk.” There suddenly was a personal sadness and a weight in his words. I was suddenly no longer a welcome guest, I was an intruder. But Lyubimov informed me of that in such a subtle way I didn’t realize it until much later. That is, I did get up almost immediately. I turned off my tape recorder, thanked him for the talk and the tea, and I went home right then. But I did not know why I was doing it. I simply did it instinctively, as an actor might responding to direction from a master director.

Every time I ever spoke to Lyubimov after that I tried to say as little as possible. I’ve used too many words here. But I hope some have meaning. Today, after all, is special. Yury Lyubimov left us today. May he rest in peace. We’ll never again know his likes.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Freedman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.