When we talk to each other, there’s what we say out loud, what we wish we could say, and what we’re saying without saying anything at all.

The words we use and how we use them were continually questioned throughout the new production of Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons at the Harold Pinter Theatre, London. Written by Sam Steiner and directed by Josie Rourke, it explores how a proposed “hush law” would impact a couple as they navigate their relationship through the early stages of romance to the more mundane elements of cohabitation.

The play is made up of a number of short scenes, giving the audience an opportunity to see how the communication between Bernadette (Jenna Coleman) and Oliver (Aidan Turner) evolves. It explores whether they choose to say what they need to, what they want to, what they don’t want to and what they avoid saying to save hurting each other.

When we communicate, we do so using both verbal and nonverbal cues. These can include vocal tone, facial expressions, gestures and changes in body posture. But whether the other person picks up on these cues is another matter. In theatre, gestures, expressions and tone must be considered and used with intention so that they serve the narrative of the play.

Director Josie Rourke and movement director Annie-Lunnette Deakin-Foster would (or should) have approached this play knowing that every movement these actors make, whether by design or by habit, will add to our understanding of not just what they are communicating to each other, but also how they are communicating that to us.

How do Rourke and Deakin-Foster show us the nonverbal in an auditorium while keeping a naturalistic style? By use of physical gestures and posture combined with silence to give meaning to each movement and each moment.

Loaded gestures

A good example of implied meaning in physical gestures that is subtle enough to be natural is when Bernadette frequently puts her hand over her mouth mid-speech. It is as if she is trying to stop herself from saying what she wanted to say or to stop herself from talking over Oliver.

It frequently looks like part of her sentence structure, much like a comma or a full stop, and manifests where we would find a forward slash in the script, splitting many of the interactions.

Bringing our hands to our mouths can imply we don’t want to say what we need to, or we are fearful of the response to it. In Bernadette’s case, it gives the impression she is holding her tongue, that she is reluctant to or is unwilling to speak truthfully to Oliver, or is stopping the compulsion to keep talking over him which she does frequently throughout the play.

Oliver in comparison uses changes in body posture, frequently leaning away from Bernadette, breaking a face-to-face interaction, particularly when being asked a direct question. This is often done with his hands in his pockets.

Again, much can be understood from this perceived hiding of the hands. Joe Navarro, an ex-FBI agent and expert in non-verbal communications, suggests that when people hide their hands, those listening will believe something is wrong, that those speaking are less open, less honest.

In Lemons, this is certainly true. Bernadette asks Oliver about the nature of his relationship with his ex-girlfriend Julie many times. His verbal answers are always evasive, saying they broke up “because it was time”. When he does attempt to admit to wrongdoing, the script is littered with silences and pauses.

What is said in the silence

These silences and pauses also give the audience clear clues about this couple’s ability and inability to communicate honestly. Steiner’s use of the “Pinter Pause,” a theatrical device named due to its prolific use by playwright Harold Pinter to more accurately depict the natural pattern of human speech, helps the audience to understand Bernadette and Oliver’s jumbled and random conversations.

Pinter said his use of pauses and silences were because, “We communicate only too well, in our silence, in what is unsaid, and that what takes place is a continual evasion, desperate rearguard attempts to keep ourselves to ourselves.”

In Lemons, each actor frequently drives forcefully through the text, giving way to emotional dynamics and character intentions, and then suddenly holds the stage in silence, gazing at or away from their partner, hoping that what isn’t being said out loud is somehow heard in the silence.

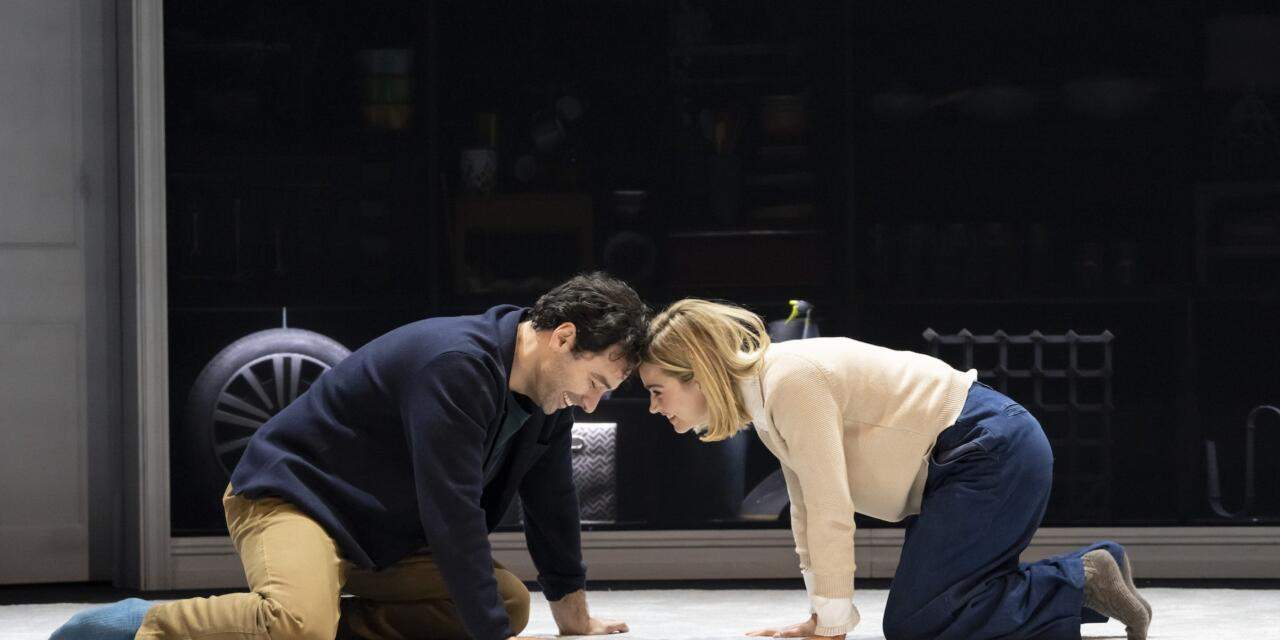

When words fail (or are banned) the characters laden their silences with meaning. PC: Johan Persson.

Censorship of language is explored as we negotiate our way through the actors’ body language. Attempts to guess what they were thinking by looking into each other’s eyes were perhaps the most crucial moments of the characters’ interaction, acknowledging that they, and we, need physical information to fully know what one another is truly saying.

Towards the end of the play, it becomes clear that these two people, who had once shared a close relationship, are no longer able to communicate honestly – verbally or nonverbally. Eventually restricted to just 140 words a day, they both use short-form phrases to get to the point quicker. But even then, they fail. When Bernadette utters, “I saved my words for you, Oliver,” perhaps she really had been saving them all along.

Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons is on now at the Harold Pinter Theatre, London, until March 18; Manchester Opera House March 21 to 25 and Theatre Royal, Brighton March 28 to April 1.

This article was originally posted on theconversation.com on February 21, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anna Tringham.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.