Three red chairs on a stage, at the upstairs bar, overlooking the Food Court at Freedom Park. Enter Makinde Adeniran and Najite Dede, performing the geriatric characters in Sefi Atta’s A Wake, at the service-of-songs for the late Chief Oni, a Godot who never appears but whose wake is the theatrical setting for Lagos gossips, uninvited Mogbo-moyas (I-heard-So-I-Came) and the social awakening of a sleeping spouse.

Sefi Atta, the playwright, is a scion, wife and mother from some of the first Nigerian political and intellectual families. A Wake opens the door into the idiosyncrasies of our old moneyed class, Yoruba families with British chequebooks from legitimate earnings; church-going and grey-haired couples who understand the complexities of billion-naira investments, trophy wives and chauvinistic husbands from good homes. However, in the role of the Gossip, played by the sensational Omoye Uzamere, we observe the self-made, unstoppable Lagos social climber who dishes the dirt on great men, munching appetisers hustled from servers and singing hymns off-key, loud and uncontrollable like a Nigerian problem. Yet her mouth is the bell, the resolution of the show, and a wake-up call for sleeping housewives.

On that cold Sunday evening in April, it’s a double bill at DePark Theatre; immediately after A Wake is a performance of Angst, the play by Austin Awolonu, an industry veteran and Ikorodu community benefactor. Two ladies in black leather are flogging theatre directors, like Toyin Oshinaike, who directed the show, for the terrible state of Nigerian theatre. It’s an energetic, sarcastic and sadistic exhibition of the horrors facing theatre practitioners in the country: flogged by the state of the country, humbled by poverty, unappreciated by the public and unfairly criticised based on Western standards that don’t fit the Nigerian narrative. Why is our writing ungrammatical and different from that of Western English speakers? Why are Nigerian stage performances criticised as though we actually have an industry of practitioners, when we are just hungry citizens competing for toilet space, for a chance to excrete art and express our muse in a third-world country?

No, the Western standards of criticism do not apply here. We are orphans acting plays on empty stomachs before an improvised audience in a country in recession. We are angry. The theatre is hungry. So watch us perform our hunger, keep your well-fed opinions to yourself and wonder how the show continues to go on.

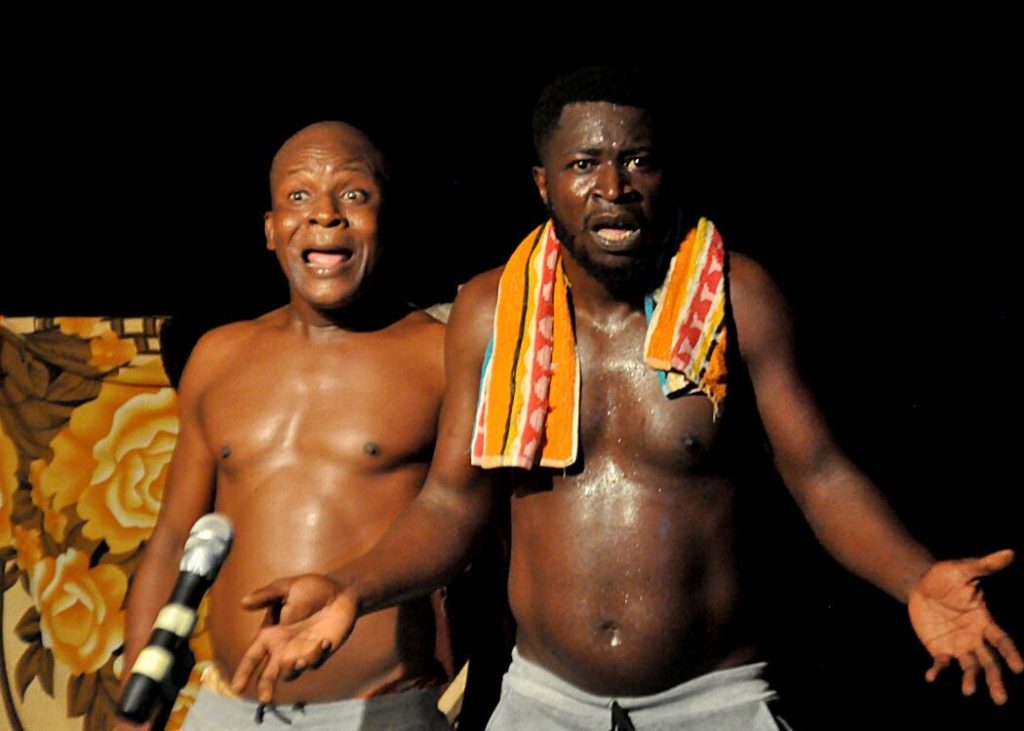

Toju Ejoh and Toyin Oshinaike are some of the most underappreciated, unrewarded and prolific practitioners in Nigerian theatre at this moment. Mr Ejoh directed Sefi Atta’s A Wake and performed multiple characters alongside Mr Oshinaike at the Majmua Theatre Easter presentation of Wat’s Dis All About, the Nigerian street version of Woza Albert!, the South African play by Barney Simon, Mbongeni Ngema and Percy Mtwa.

Wat’s Dis All About explores the arrival of the Nigerian messiah, our saviour from bad governments, foreign exploitation and national ignorance. The two-man cast showcases comic characters, their expectations, and the anticipation, arrival, reception, death and resurrection of the Nigerian messiah. The show is a vignette of colourful characters and settings, from the police station to the prison cells to the bus stops of Lagos; from the Hausa-accented general coming from the frame of a television set to an interview of a reincarnated Fatai Rolling Dollar, the legendary Nigerian musician. At one point the actors are costumed as children selling on the street, with lots of famous name-dropping; references from Nigerian disasters like MMM, the Russian Ponzi scheme that wrecked millions of Nigerian investments; and cameo representations of internet celebrities like Jumoke-the-bread-seller-turned-fashion-model. The changes of settings and characters are well-timed, fast-paced and sequential, with lighting directed by Biodun Kassim, the rising-star actor and co-founder of Majmua Theatre.

The theatrical collaboration of Toju Ejoh and Toyin Oshinaike is a worthy academic thesis. Moreover, the origin of the most famous collaboration in Nigerian theatre remains a story yet untold.

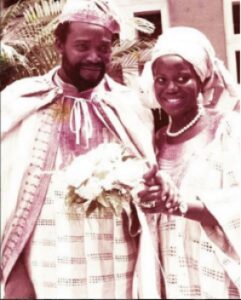

Olu Jacobs and Joke Silva circa ’82

Olu Jacobs and Joke Silva are the oldest, most popular and most celebrated partnership in Nigerian theatre. Jacobs is our London-trained thespian, born in 1942 yet dashing with his wise-white hair, voice of the gods and personality of the quintessential gentleman. The joke is the Nigerian screen and theatre deity without peer, evergreen like Meryl Streep, revered and respected beyond her fifty-five years on earth.

On the anniversary of Nigeria’s twenty-fifth independence celebration, Joke met Olu at the National Theatre, in 1981, and married him in ’82, when they also began working together as the Lufodo Group, a business and artistic enterprise comprising the Lufodu Academy of Performing Arts, the most prestigious training institute in the country, and other profitable initiatives.

Nonetheless, their foreign contemporaries who attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and the Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art in London have enjoyed better opportunities abroad. Jacobs starred in several British television shows and theatre in the 1970s before returning to Nigeria with the hopes of developing our industry. Here is a man who was directed by John Irvin in The Dogs of War and Roman Polanski in Pirates. Here is a woman who starred in a major role alongside Colin Firth and Nia Long in The Secret Laughter of Women. These are Oscar and Tony Award materials demystified by the Nigerian condition and shortchanged by a lack of opportunities, yet Olu and Joke created breathing room for the next generation of Nigerian collaborators, such as Toritseju Akiya Ejoh and Zara Udofia-Ejoh.

Toju and Zara. Photo courtesy the couple

Toju and Zara met on set, rising stars in their own right, without need for the other except to succeed together and navigate the minefield called Nigeria. Toju had the name, Oxygen, but Zara had the paying commission, took the initiative and together they established Oxzygen Koncepts and Productions Limited. Their business resumes consist of world-class productions; they require no advertisement, only that their personal lives, the ingredients for a successful partnership, be told.

They were colleagues and accidental acquaintances living in the same neighbourhood, Festac Town, the Lagos suburb developed by the Olusegun Obasanjo military administration in celebration and to host the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture in 1977. The National Theatre was built for the same purpose. The Festac neighbours would meet and fall in love, but their vibrant town was no longer a hub of creative talents. It had become a mini city that choked their dreams, localised their existences and didn’t allow them the freedom to grow, to metamorphose and to see beyond their immediate environment.

Zara recognised that she needed to break out of the beloved circles that stifled their ambitions. Toju was too much of a man to recognise the obvious. How then do you convince a man you love to leave his home, the community where he’s known and respected, for a whole new environment where you guys could plan without distractions, excel without pressure and create new adventures on your own? Toju’s mother supported Zara, and the newly married thespian packed her things and left. Via luck, wise counsel and the guidance of his parents, Toju chose to remain married over the company of his childhood friends and supporters.

Nowadays, in their quiet Surulere neighbourhood, Zara hosts her husband and his midnight friends whenever they bounce in after productions, theatre performances and creative chats where ideas are born and executed. She also produces the shows she likes, performs on screen and stage, and manages Oxzgen Koncepts as the CEO. It takes two or more to survive Nigeria, to be a theatre practitioner and to live one’s dreams.

It takes a critic, behind the curtains, to understand why the show works and how it can improve. Nigeria has also become a place where theatre critics are PR executives masquerading as journalists, collecting bribes to publish reviews and to feed their families. How can the industry grow without the proper funding to remain honest, ethical and operate on a par with international standards? The city, theatre and critics must find legitimate ways to work together.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Amatesiro Dore.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.