While at his family estate in Melikhovo in the early 1890s, Anton Chekhov dreamt of a monk floating across the fields. When he awoke, he decided to write a story. The result was The Black Monk, first published in 1894 in the journal Artist. It describes the mental breakdown of Andrei Kovrin, a talented scholar who retreats to the country estate of his former guardian, Yegor Pesotsky, to recuperate from overwork. Pesotsky, entirely devoted to his extravagant, ornamental gardens, worries over his legacy and encourages a relationship between Kovrin and his daughter Tanya. As Kovrin grows closer to Tanya, he begins to see visions of a black monk who convinces him that he is a genius, chosen by God to save mankind from suffering. Kovrin’s initial ecstasy turns to horror as both he and Tanya, whom he marries, question his sanity. He “recovers” under Tanya’s care, but ultimately abandons her and their settled, seemingly mundane life. Suffering from tuberculosis, he is visited once more by the black monk who confirms his genius just before his death.

Chekhov’s story immediately inspired confusion and even fear in its readers. Friends worried about Chekhov’s own health—was he suffering from depression? Chekhov responded that he simply wrote a “medical story,” a history of a patient’s madness, in a mood of “cold reflection.” The Black Monk, however, continues to puzzle readers to this day. Is the monk an evil genius or a benevolent one? Are we supposed to be content with a quiet life or to strive for something greater?

These questions attracted the celebrated director Kama Ginkas to Chekhov’s story and inspired his staging of The Black Monk at the Moscow Theater of the Young Spectator (MTYuZ) where it premiered in 1998 and remains in repertory. A beautifully filmed performance is now available in select American and British cinemas as part of Stage Russia’s wonderful series of contemporary Russian theatrical productions.

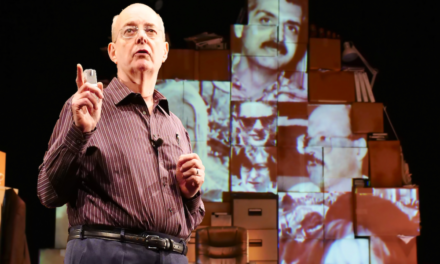

Born in 1941, Ginkas survived his early childhood in a Jewish ghetto in Lithuania and moved to Leningrad to study directing in 1962. His independent, innovative style made finding work difficult, and he nearly gave up on the theater in the 1970s. With a move to Moscow and the new openness of perestroika in the 1980s, however, Ginkas found his place at MTYuZ where his wife, Henrietta Yanovskaya, was named artistic director. He has been directing groundbreaking productions there ever since.

Ginkas rarely stages traditional plays; instead, he creates his own shows based on literary texts, primarily prose. Ginkas is extremely faithful to the language of these texts; in The Black Monk the actors give voice to virtually every word of the story, even in the form of spoken stage remarks such as “he said” and “she said.” The third-person narration is divided between the characters who sometimes fight over lines and often employ exaggerated tones of voice. Characters frequently take control of lines associated with each other, and they often contradict their words by means of their actions. This interplay of distinct voices is amplified by the inclusion of a quartet from Verdi’s Rigoletto which is heard repeatedly throughout the performance. Initially, the characters sing the quartet in Russian in playful counterpoint, but, as Kovrin’s illness takes over, their voices collide more than blend. Kovrin’s visions of the monk are accompanied by an Italian recording of the quartet which only Kovrin can hear. The music separates him from the other characters and from the physical world around him.

The sense of separation is evident in the set as well. Designed by Sergei Barkhin, Ginkas’s longtime, highly decorated collaborator, the performance is centered on a small stage which contains a simple wooden gazebo and pair of chairs surrounded by a field of bright peacock feathers—a fanciful representation of the Pesotsky garden gorgeously rendered in the Stage Russia HD production. Like the music, the garden’s lush beauty deteriorates over time as Pesotsky and Kovrin tear up the feathers in their increasing dismay. At the end of the performance, the claustrophobic, barren nature of the set is emphasized when the gazebo is bordered up in a futile attempt to contain the monk.

Not only can the monk escape this enclosure, he can also easily transcend the boundaries of the garden. The performance is held not on the main stage of the MTYuZ, but on the balcony of the theater. The audience sits around three sides of the stage, no seat more than a few rows away. The “back” of the stage is in fact, empty space—a full story drop between the balcony and the main floor. Kovrin repeatedly tests this boundary, swinging on the garden gate over the abyss, while the monk magically emerges from and descends into its depths. His actions are at once magical and unnerving; accustomed to the tight space of the garden, the viewers are disrupted by reminders of the expanse beyond the Pesotskys’ world. This aspect of the performance is perhaps the most difficult to capture on film; the sense of suspension is much stronger for theatergoers seated on the balcony itself. Nonetheless, the tension between the “reality” of the garden and the “otherworldliness” of the monk carries over to the cinema audience.

The filmed performance excels at conveying the powerful work of the actors, a remarkable ensemble featuring Sergey Makovetskiy as Kovrin; Igor Yasulovich as the black monk; Valery Barinov as Pesotsky; and Julia Svezhakova as Tanya. The thoughtful framing of the characters and the frequent medium shots and closeups highlight the emotional depth of their performances.

Ginkas has staged two Chekhov stories in addition to The Black Monk: Lady with the Lapdog (2001 premiere at MTYuZ) and Rothschild’s Fiddle (2004). Together they form a trilogy which he has informally titled Life is Beautiful. Ginkas sees man’s desire and failure to live life fully as the central narrative thrust of all three shows, and of Chekhov’s work in general. He highlights the Chekhovian tension between the beauty of life and the tragedy of how it is lived. All three of these shows have reached audiences in the United States: Lady at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, MA (2003); Fiddle at the Yale Repertory Theater (2004); and now The Black Monk in theaters across the country and in the UK. It would be wonderful to see Stage Russia capture all three of these performances for audiences—both present and future—around the world.

Sarah Clovis Bishop is Associate Professor of Russian, Willamette University

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sarah Clovis Bishop.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.