Jane Eyre is one of those mythical stories that make their home in your imagination. Where they can chat, sing and dance through your unconscious for years and years and years. First published in 1847 by Charlotte Brontë, it has been adapted countless times, in a large number of different formats and styles. This superb version, devised with the original company by director Sally Cookson, has had, like its eponymous heroine, an epic journey: first staged as a two-part show at the Bristol Old Vic in 2014, it was at the National Theatre in 2015 as a newly reworked single, 200-minute drama, and this year a recast version of Jane Eyre is on a nationwide tour.

The Bildungsroman story is familiar, but here it appears completely fresh. It begins with a baby’s cry as Jane (Nadia Clifford) voices her own birth. As her parents, then her kindly uncle, depart this life, the orphaned Jane is left in the care, or rather the couldn’t-care-less, of her Aunt Reed and the sanctimonious Mr. Brocklehurst, head of Lowood school. At first, the tale is one of brutality, and of abuse, and then of loss, as Helen Burns, her childhood friend succumbs to consumption. In this part of the story, the emotional fuel is provided by a profoundly moving sense of justice. Jane’s cry of “Unjust! Unjust!” is the keynote moment.

In the next part, the iconic meeting of Jane and Rochester begins with his expletive-enhanced entrance and a great turn by Paul Mundell as his faithful dog, Pilot. Their gradually developing relationship, here given room to grow, is not a cozy romance, but a much more fraught and furious affair, with Bertha, the madwoman in the attic, making her presence felt almost from the start. By casting Melanie Marshall, a singer with an imposing physique, to double as Bertha, Cookson restores a dignity and humanity to this character. With Adele, Rochester’s daughter, also given a full role to play, this section mixes humor, love, and danger.

The final part, when Jane flees and finds temporary comfort in the rather severe St. John Rivers household contrasts well with the more optimistic emotions that precede it. But it also builds up to a climax in which she returns to her past, and finds that it has been devastated. Cookson’s great insight is that Jane is not a rom-com sop, but a fiercely independent woman who not only has a burning sense of justice but who also learns from her experiences: the death of Helen, for example, teaches her forgiveness. In scene after scene, she stands up for herself, even when it gets her into trouble.

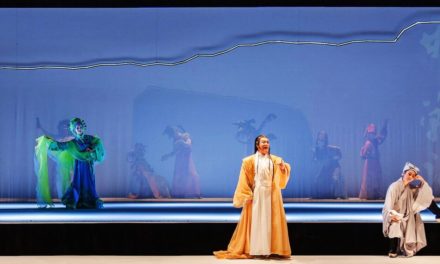

Michael Vale’s impressive set uses a construction of frames, platforms, and ladders to create a versatile environment for the action. With an ensemble of three musicians (playing drums, bass, and piano, but also chimes, guitar, and accordion), this bare setting can become the Reed household by an addition of severe family portraits or Lowood by the display of children’s dresses. Window frames admit light or suggest enclosure. With an exceptionally active and sure-footed cast, the wooden planks are transformed into a chilly classroom or, with the simple addition of hand-held lamps, the empty corridors of Rochester’s Thornfield Hall.

While the music, played by Matthew Churcher, Alex Heane, and David Riley, weaves a spell by using an eclectic combination of hymns, folk songs and classics (at one point, Noël Coward’s “Mad About the Boy” enhances the emotional landscape), Benji Bower’s haunting score and Aideen Malone’s lighting gives the best scenes a satisfyingly gothic feel, and the blaze of red when Jane is thrown into the Red Room is brilliantly done. The main actors and ensemble scramble over the set in Cookson’s fast-moving production, which has set piece coach journeys (running on the spot as the towns whizz by, then stopping for a “piddle break”), passionate encounters and heartfelt declarations. At one point a dress is flown in, at another the set’s Shaker aesthetic chimes perfectly with the religious tone of the story. Real flames consume Rochester’s bedroom, and then the mansion.

With its high emotions and scalding sense of justice, Jane Eyre is melodrama, and then some. Rochester arrives in a blaze of orchestral music while kettle drums pound out his entrance. Cookson emphasizes not only Jane’s life journey but the discipline that religion imposes in Victorian times, while folk songs suggest a wider society. Her transformation scene in which she becomes an adult is beautifully done, and the play’s ending implies a cycle of life and of female experience that is strikingly apt. Using a device pioneered by Shared Experience, Jane’s internal monologues are conveyed by a chorus of actors.

Nadia Clifford’s Jane and Tim Delap’s Rochester offer a study in contrast: he is large and thunderous while she is small and calmly plain-spoken. He has a roughness, an abruptness and an almost boorish indifference which gradually melts into deep feeling, while she discovers love through the agonies of jealousy and rejection with an openness to experience that is a delight to watch. In support, Lynda Rooke does good work as both Mrs. Reed and Mrs. Fairfax, and the rest of the cast — Hannah Bristow, Evelyn Miller, and Mundell — play all the other parts. It’s a long evening, but an exhilarating one: this is a stupendously exciting piece of theatre that is a moving portrait of a plucky character. Reader, I cried my eyes out.

This post originally appeared on Aleks Sierz on September 27, 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.