The acclaimed Franco-Uruguayan playwright Sergio Blanco was in Madrid to stage his play Ostia at the Pavón Kamikaze Theatre while Thebes Land, another of his plays, continues its run, directed by Natalia Menéndez.

My year of theatre ends with Blanco. With Sergio Blanco. Fade to white, like the life of Roland Barthes, who was run over by a laundry van (he had a death worthy of himself, “a semiotic death,” says Sergio). Pasolini also had a death worthy of himself, violent, exaggerated, though lacking in humanity, says Sergio, the humanity that impregnates the entire body of work of the Friulian poet. Pasolini had a Pasolinian death in Ostia, the coastal town 30 kilometers west of Rome that was an essential trade port for the capital of the Roman Empire about 2,000 years ago. Through this same port came malaria, that bad air that flipped the switch on the decline of Rome. Pasolini died in Ostia, then a fascist bastion, and still today a breeding ground for the extreme right. He died for being a mosquito, some would say a fearless fly, but no, a mosquito whose bite is bringing an end to today’s empire. Call it what you may.

When I arrived, in silence, in that room with big, tall windows on the first floor of the Pavón Kamikaze Theatre, Sergio Blanco was speaking with Paloma Cortina of the National Radio of Spain. I caught them struggling with the concept of textcentrism. Sergio is not textcentrist at all, and excuse me, Paloma, for intertwining your interview with mine. He writes plays, and when they move on to a production team, “the author is nothing more than any other crew member, like the lighting designer, the stagehand, in service of the production. If there is any authority there, and I doubt it, it belongs to the director, who can do with my play whatever he wants.” Sergio Blanco talks a lot and well, and he says emphatic things, and he plays at erudition bringing up names and dates, but he’s not solemn, he’s not tiresomely intense. His manner of reasoning is pleasant, but he puts ideas and affirmations out there that could start an Olympics of controversy. Because he says, for example, that he likes borders. Because they separate us as much as they unite us. Because he says that what John Lennon sang was nonsense.

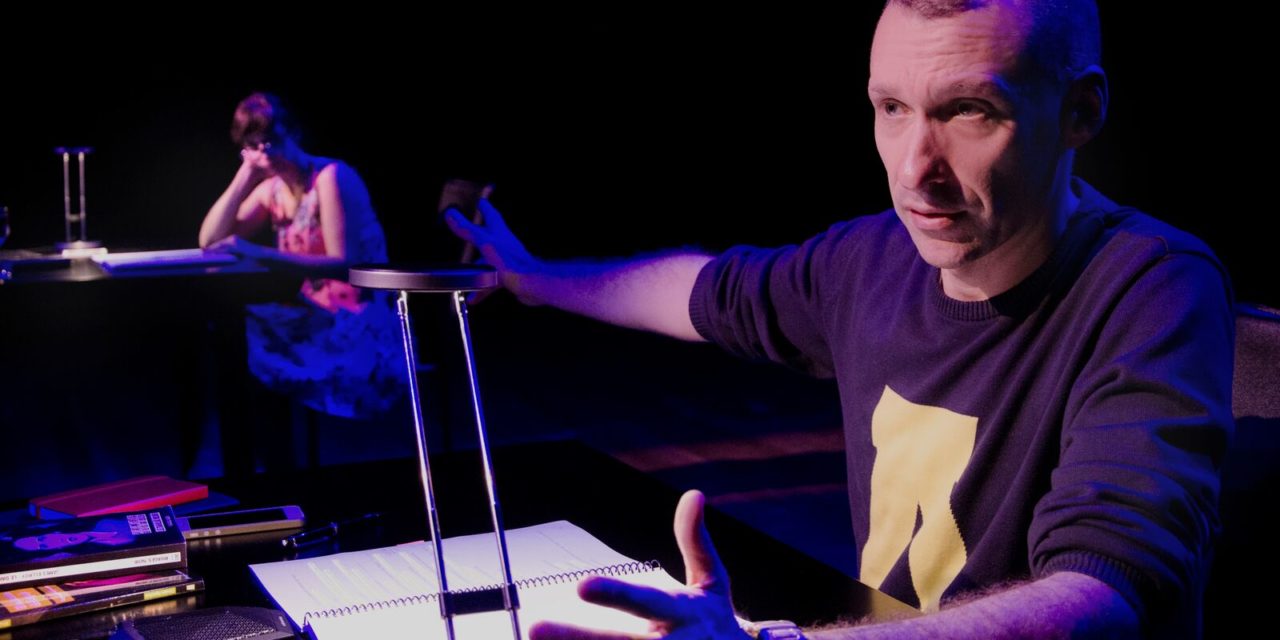

Franco-Uruguayan playwright Sergio Blanco is in Madrid, taking in the production of his play Thebes Land, and staging another of his works, Ostia, at the Kamikaze Theatre. Ostia is a piece of autofiction so full of autofiction that it can only be performed by himself and by his sister, the actress Roxana Blanco. I remember three or four people, in the last two months, urging me: don’t miss out on the opportunity to talk with Sergio Blanco, he’s a guy with an overwhelming, brilliant, amazing way of speaking…and so many other striking qualifiers. This must have been said to at least four other people, my four press colleagues who had interviewed him before I did on the morning of December 28. Innocent. Mine was the last appointment. We talked for thirty minutes at most. Before starting, between the moment Paloma Cortina grabbed her coat and I took mine off, Sergio said to us, “what you do is very difficult. Journalism is awful, at least to me. I did it for a while and always ended up in a heated debate with the person I was interviewing. And no, that’s not journalism.” No. I don’t know. It’s strange. You put yourself in front of a guy you don’t know and you ask him to tell you things about himself, about what he does, about what he thinks. It’s truly strange.

As the conversation goes on, I begin to feel, in a way, united with Sergio Blanco. I feel that Pasolini unites us. The first thing I do is shake off my fear and uncertainty about being in front of him and telling him yes, well, I’m the fifth journalist who has interviewed you today, and I’m sure you’re tired of saying the same thing, and I hope you can forgive me if my questions aren’t original. But I had an ace up my sleeve. Exactly two weeks ago I was in Ostia on a pilgrimage to the place where they killed Pasolini. It was a most unpleasant, grey, windy, and cold morning, one in which the Tyrrhenian Sea was especially vicious and voracious, having dragged away half the beach with its giant waves. Dozens of restless seagulls flew overhead, as we marched on, determined, along the promenade, deserted at noon during winter, with our gaze fixed on our destination: Via dell’Idroscalo.

Ostia Beach. Photo by the author. © LaconT

Why does one write autofiction?

It’s like a need arose in my body at a certain age, a desire that my body be able to contain other bodies, that I can tell my story and end up finding other stories through mine. If there’s one thing that interests me about autofiction, it’s the intersection of the real and the fictional, something that has existed in the history of thought since the very beginning. The first instance of autofiction was Socrates: “know thyself.” After that, you have, Saint Peter, Saint Augustine, Saint Teresa of Ávila, Rousseau, Montaigne… I’m interested in the notion of owning the lie, which is what distinguishes autofiction from autobiography. When you write an autobiography, as Lejeune says, you have to make a pact with the reader that everything you say will be the truth. Autofiction proposes recognizing the lie, and in the theatre, this becomes even more fascinating, because I’m going to lie to you, right here and now, from a foundation of truth. Autofiction gets at the heart of art and creation. It is, and it isn’t. As suggested in Ostia, to be or not to be becomes to be and not to be, because you are at once with yourself and being untrue to yourself.

When I read Thebes Land I wrote down something that Martin says upon discovering the mechanics of a play: “So, nothing is anything?” Something that Roxana also says to Sergio in Ostia.

The world of nothings, as Borges would say, art is the world of nothings, where nothing is anything. Autofiction addresses this theme just as it also addresses another big theme that is the self and the other, the boundary between the self and the other, in talking about you I’m going to talk about me, as Walt Whitman says, “and what I assume you shall assume, for every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

So, on the stage, the territory of fiction, you enter into a pact with another, with the audience, a game of reality and fiction based on a lie. But what happens in life, the territory of reality? Might one also feel tempted to play at blurring the lines between what is and what isn’t?

No, autofiction in art only. The temptation to lie can be so dangerous that I reserve it only for the field of creativity. In the field of academia, for example, I would never allow myself to lie. Yes, it’s true that I’m very hyperbolic in Facebook, for example. I exaggerate, but the limit is clear to me. And because I happen to make autofiction, people think I live in a permanent autofiction. The further autofiction is away from you, the better it is. It’s not the same as biodrama or theatre of the real or documentary theatre, it has nothing to do with them because these genres deal with reality. Autofiction fails when it doesn’t let go of reality. It has to detach from the documentary. The further away it is, the more it fictionalizes, the more it disguises, the more it transfigures, the more it deforms reality, and so the more it triumphs because fiction comes in to broaden one’s little story.

There’s something fascinating about Ostia, in the play, in the way it subverts the logic of time and gives it elasticity, malleability…

I am convinced that time is not what the bourgeoisie created as a form of domesticating and managing human communities. Time is actually a really new idea. Time doesn’t exist, as Borges would say, or Saint Augustine, who says that what we believe to be yesterday, today, and tomorrow, is all just the present moment. The present of the past is a memory, the present of the present is what we see, and the present of the future is that which we hope for. Wonderful. And Borges says that the present moment doesn’t exist because it has already passed, and the past is nothing. These ideas are being confirmed by science as it increasingly moves away from positivism. We are bound by time, but we are capable of building time, of manipulating it as we want. This notion that the past is as open as the future, that the past isn’t a static experience, is awful, but fascinating. It is very interesting to know that the past is as unknowable as the future. Those who have siblings know it well, and that’s why Ostia deals with siblinghood, because you start talking with your brother or your sister about a memory, and everyone tells it differently. Who is telling the truth? It’s like when Proust frees himself in his last volume, In Search Of Lost Time, when he realizes that the past isn’t in the past but in the future. The past is in me, I don’t have to go out looking for it, it’s in the hope for what is to come. This equation that mixes past, present, and future is so very lovely to me. And we have a language with which each person can do with time what he or she wants. It’s very liberating.

Is autofiction the last refuge of the postmodern self?

Possibly. Dubrovsky started to explain autofiction in the 1970s because he was heir to a period that allowed us to return to the self at the end of the Cold War through the fall of the great ideologies, through the emergence of movements that aren’t political but rather social, gay movements, queer movements, the appearance of AIDS, which generates movements that fight big pharma, certainly Foucault’s thought, the return to the self as place, Lipovetsky’s thought, self-centeredness, not as a closing-off but as a way of understanding that battles no longer happen because of political parties or unions, but rather because of demands from groups, may no one speak in my name, let me defend what happens to me…All this helps to create the culture of the self with postmodernity, towards the end of the 20th century. But unfortunately, it falls in the hands of consumer society, of mass media, of the society of the spectacle, and it becomes totally perverted because we end up undoing this culture of the self and turning it into the worship of the person, selfism, narcissism, the selfie. It’s like being in a constant state of a sort of onanism, not that I condemn masturbation, just like I don’t condemn suicide nor celibacy. These seem to me totally admirable ways of managing oneself, but there is something terrible in the closing-off of oneself. It’s not postmodernism’s fault, nor Lipovetsky’s, nor Foucault’s, nor the self’s, which has been changed by consumerism.

Monument to Pasolini in Ostia. Photo by the author. ©LaconT.

In the last years of his life, Pasolini warned, time and time again, he practically yelled it from whatever platform he had available, he said that whatever characteristics were genuine, were authentic, that these would be devoured by consumerism.

Pasolini used to say that capitalism could be more dangerous than fascism because it was odorless and colorless.

To him, capitalism was the perfect evolution of fascism. And lo and behold here we are today, all equalized by our consumerism.

That’s exactly what Salò, Or The 120 Days Of Sodom shows; many people said it denounced fascism. No, it denounced the bourgeoisie, FIAT, Alitalia…and here we are.

I’ve trained as a theatergoer, as a theatre journalist and practically as a man by being stuck in my seat in the stalls over the last fifteen years. One of these decisive impacts came the first time I watched a production by Angélica Liddell. It was at the Sala Cuarta Pared (Fourth Wall Theatre). The play: And The Fish Rise Up To Set War Against Mankind (Y Los Peces Salieron A Combatir Contra Los Hombres). At the end of the show, Angélica lifted her shirt and covered her head with it, like soccer players do when they score a goal, they run around the field showing their enviable six-pack abs or some other shirt with a message hidden up to that moment. Angélica had a photo of Pasolini on her undershirt. How did you get to know Pasolini?

At the age of 14, through a literature teacher, because I would talk with her after school, and one day she told me about Pasolini’s films. I went to see one of them in a film library, unbeknownst to my parents, because I was 14. I go in and see one of his films, and I’m enchanted. I’ve never shared what film of his I saw first, but since then I’ve seen all of them. I start to see this thing that Pasolini has, that’s not monolithic, but irregular, that has many different poetics that form a single poetics. I began with film, but little by little, I started watching his interviews, reading his work. Between 14 and 18 years old…I start to read everything because he is a great writer, a great poet. What Moravia said at his funeral: there aren’t many poets, the centuries give few poets, Pasolini was one of them. He was a great poet. And he’s also a man of impeccable ethical behavior, I’m not very interested in artists’ personalities, but Pasolini’s is fascinating because he was a man of great freedom, detested by all institutions, be they left-wing, right-wing, religious, political, academic…even today academia has condemned Pasolini terribly because he defended dialects, he never defended the left-wing intellectual. He was a guy who hung out in the underworlds, with the ragazzi. He lived his homosexuality in an incredible way. He was ahead of his time in every way, and all this fascinated me at 15, 16, 18 years old, even his death, which was at once totally Pasolinian and not, because it lacked the humanity that Pasolini had. Because deep inside his thought, there is a tribute to humanity, as hadn’t been seen in postwar Europe for a long time.

A death full of symbolism, the death of a free being in the neofascist bastion of Ostia…

Something like Christ sacrificed, quartered, in awful conditions, in that place where Mussolini tested his urban planning. They condemned Pelosi, a kid when you know the system was behind it…it doesn’t matter if it was the Vatican or the Mafia or the State, just suspecting that it could have been them is enough to call them guilty. There is the presumption of innocence, sure, but we know that the Vatican banned all his films, and we know the significant role the Vatican plays in the Italian political collective. It gets presidents and senators elected, ministers ousted…Or the Communist Party, that was awful toward him, who never forgave his true communism, he said.

I had been to Ostia several times because I go to Rome quite often for work and because it’s a city that fascinates me, and I repeatedly visited the ruins. If you love Pasolini, you go to this place as if you were on a pilgrimage, and also because it’s like something out of the movies, those vacant lots, that road…

“The first duty of intellectuals today would be to teach people not to listen to the linguistic monstrosities of the Christian Democrat bosses and to scream with disgust at every word they utter. In other words, the duty of intellectuals would be that of rejecting all the lies which through the press and above all through television inundate and suffocate the admittedly inert body of Italy.

Indeed almost all the intellectuals in the opposition substantially accept what the Christian Democrat bosses accept. They are not at all scandalized at the monstrosity of the language of the Christian Democrat bosses.”

Pasolini, March 1975

Ostia condenses the history of Italy, from Aeneas to Mussolini. The sickness that ended the Roman Empire entered through its port. It was there that this other mosquito died, the one who was trying to bite this other empire, until they squashed him with a swat.

Art doesn’t create a revolution. That is a bourgeois thought that the bourgeoisie invented to get out of it. If you want to start a revolution, you have to look somewhere else to start it. But yes, Pasolini acted as a mosquito that could put an end to an empire. It’s a good thing that empires come to an end.

Do you believe we’re seeing the end of an empire?

When does the Roman Empire start to fall? When one starts to see the size of the emperors. If you look at the American empire, with the size of the latest presidents, it’s pathetic. The last 40 years. What they have now is a caricature, but the whitest black person on earth was also a caricature. Chomsky said something extraordinary: it’s normal for people to celebrate Obama coming into power, it’s not so strange, says Chomsky, don’t be amazed, in American culture, black people–I’m going to use a bad word, but I use it in order to quote Chomsky, I never say bad words–in the United States, black people clean up white people’s shit, and after Bush’s shit, only a black person could clean it up. The Bushes, both pathetic, Clinton, all of them crooks, you start seeing the decline, the paradox, the vulgarity…Kissinger, who sent dictatorships to Latin America and who ordered the killing and torturing of bodies, Nobel Peace Prize, and Obama gets a Nobel Prize, too, when he has 7 open war fronts across the world. These are all symptoms of an empire that is coming to an end. I believe the American empire is ending, I hope for its end, I celebrate it, I do what I can so that it will end, just as in its moment I would have done it with the Roman Empire. They have nothing to do with one another although they are sometimes compared. The Roman Empire was I come, you keep your language, do whatever you want, keep your culture, and from now on you’re Roman citizens. Have you ever seen an American do that to someone from Afghanistan? Rome was an empire that spread, it was obsessed with borders, but it didn’t impose its McDonald’s, its Coca-Cola, it respected the culture of each place. They were so brilliant that when they went to Greece they said: look at this, how interesting, it’s called theatre, let’s leave it, let’s bring it. Yes, I believe we’re living the end of an empire.

What is it like turning your sister into a character that plays herself?

It’s strange. I wrote the play and then gave it to her to read because there are other family members involved, not just her. The first person to do this in the history of art was El Greco, who painted himself in The Burial Of The Count Of Orgaz, and he painted his son. He’s the first in autofiction or self-representation to include a family member. And there’s a detail in it that no one notices, that his son is pointing his finger at the priest who is burying Orgaz, who has Saint Augustine’s features, and who has Saint Paul printed on his robe. El Greco was a brilliant man who had read Saint Augustine and Saint Paul. It’s the birth of a new world in which the creator can begin talking about himself in art, and include his son. I do the same as El Greco in this play. I include my sister, and we talk about very intimate things, and I gave it to her and said, feel free to cut and add whatever you want.

Roxana Blanco in Ostia. Courtesy of Teatro Pavón Kamikaze

Do you feel a certain demiurgic power or extra responsibility?

You have to be careful when you write and involve other people in your texts, careful about what to say, about what not to say, and there is a point in my course on autofiction in which I dedicate about six classes to legality, which is also important. What you can include, what you can’t…I’ve had problems, too…well, I just wrote The Roar Of Düsseldorf, an autofiction that I wrote about a kid who committed suicide in Chile after having seen my play The Ire Of Narcissus, a show of mine. He bought tickets for his parents and when he sent them off to the theatre, he went to Uruguay Park in Santiago, Chile, and he hanged himself from a tree with a bag full of books. This really happened. He saw the play in Montevideo and went to Chile, where his parents live…he wanted to commit suicide while his parents watched the show, but the parents never actually saw the show, because they were notified and they left. This was at the Santiago a Mil International Theatre Festival, two years ago. I remember those two empty seats in the stalls. Six months later a woman writes me and says: I’m the mother of the child who died after seeing your show. At first I think it’s a joke, so I called the Chilean Embassy in Uruguay, and they confirmed the event. So I go to Santiago to meet this woman, who wanted to read the play, because they play hadn’t been published, and she wanted to know if there was any message in the play that had to do with her son.

When I spoke to this woman, the moment I first had contact with her, I started writing a play that tells all of it: The Roar Of Düsseldorf. It’s an autofiction where I go to Düsseldorf, my father has a seizure, it’s the last three days of his life (my father is alive, OK?), and I tell the story of my father’s death as I go in and out of his room in the hospital in Düsseldorf. You never find out why I’m there, if it’s because I’m writing scripts for the porn industry, which is true, I did write scripts for the porn industry, or if I’m writing for a museum about Peter Kürten, who was the first German serial killer of the 20th century, or if I’m going to convert to Judaism and get circumcised. You never find out why I’m there, but in the middle of all this, I remember the suicide episode and the play ends with the character of the mother coming to see me in the clinic.

When I wrote it, I gave it immediately to her, and I told her: I want you to be a character in my play, and later she came to Montevideo for the show’s opening. Now the production will go to Santiago a Mil, and she’s going to come with her whole family. I formed a bond with this woman. It was very hard for me. It paralyzed me for a bit…I get emotional when I talk about it…I knew I would only be able to go on writing if I could write an autofiction on this story because it was very hard for me to know that someone had committed suicide after seeing a play of mine.

Can autofiction also provide healing?

Yes, it helps, of course, writing it, naming it, saying it…it paralyzed me, you know, I was left in great anguish, I halted The Ire Of Narcissus, for a time we didn’t do it because it’s a play that ends in a suicide in a way. It caused me a lot of anguish and meeting this woman did me a lot of good, and for her, too, because she had this ghost with her, this kid was like in love with my play and planned all this…it was very hard for me. Maybe theatre isn’t just capable of doing people good but also of driving someone to kill himself. And writing The Roar Of Düsseldorf allowed me to talk about all of this. It is a truly beautiful show we’ve done and which, by the way, comes to Madrid in November for a season, along with my production that is touring now, after Argentina, the United States, Canada, Finland, and Sweden, it will come to Spain.

You tell me about the plot of this play and I think of Thebes Land or Ostia… this game of layers that is so characteristic of your texts, is it an ethical choice or an aesthetic one?

It’s more of an aesthetic one, it’s a game, it’s more like telling the audience: work with me. To call upon the audience’s intelligence, because I’m not going to give you things in baby bites. The fragmentation of discourse. I’m going to throw you some puzzle pieces, and we’re going to put the puzzle together, and it’s possible that we might never be able to put it together.

I like the mechanism of boxes inside boxes inside boxes, meta-theatricality, the cyclical returning to the same…these are aesthetic choices because they appeal to the audience, they make demands of the audience. To me, the audience isn’t a passive entity that’s just there and that’s it, it’s not I’m smart and I’m going to tell you how to create a revolution and change the world, no. I’m going to pretend I’m someone else, you’re going to pretend I’m someone else. To call for the emancipation of the audience: take this, and build with me.

Just like Buñuel who in his time opened an eye, because he understood that those other crazy guys Picasso and Cézanne had invented Cubism and that something had been broken. I believe that today that eye would be in a blender, it has exploded. All this has a lot to do with teenagers. I don’t use screens, but I do open up a thousand screens in their heads. In today’s world, we’re programmed like this, and I want to work with these elements. I condemn them ethically, it disgusts me that Nike and Adidas use them, but they, young people, are smart, they get it, and they use it. I don’t want my nephews to go to Adidas, I want them to come see Phaedra or The Trickster Of Seville or Macbeth, but to do that I need to use these elements.

I don’t really like Lehmann’s book on post-dramatic theatre because I think it’s a book full of errors, a German invention of some editor who wanted to make money, and I hate the term post-dramatic because it doesn’t mean anything from an epistemological nor a theatrical perspective; but Lehmann says something very interesting. He says that it’s the end of the Gutenberg galaxy. We don’t read the world from left to right anymore, because all these new technologies have changed our way of perceiving things. Nowadays my nephews do seven things at the same time, and they do them all well. To me, it’s essential to translate all of this if we want to grab audiences. We have to take the eye’s temperature, know what’s going on with the eye nowadays. It needs to explode and have twenty thousand windows. And in this way, teenagers become spellbound, because you make them work.

It’s not overstimulation, but rather it’s simply the stimulation they need for the world in which they live.

Exactly, and you can’t just ignore that. Every creator must understand what is happening in his time. You can’t not understand it. You can’t be unaware of it. When electricity came about we had to change the way we lit theatres. And technology is always moving forward, and there’s nothing better than to take hold of it.

Via dell’Idroscalo in Ostia, Italy. Photo by the author. ©LaconT

This interview was originally published in Godot Magazine on December 29th, 2017. Translated by Mary Allison Joseph and published with permission.

Follow Álvaro Vicente on Twitter @AlvaroMajer

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Álvaro Vicente.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.