A well-known poet and journalist, Saviana Stănescu left Romania for the US thanks to a Fulbright scholarship, and she arrived in New York just before the 9/11 attacks, which still play a role in her imaginary, alongside the Romanian revolution in 1989 and the ghosts of the past. Below is my conversation with Stănescu as a preview to a future joint endeavor to take place this fall in Bucharest, Romania – The Revolution Project.

C. Modreanu: What are the most difficult aspects of writing for theatre in a language other than the maternal one?

S. Stănescu: To be honest, I am writing mostly in English now. I am a Romanian-American immigrant playwright, working in the US, constantly living on the bridge of in-betweenness: negotiating between two cultures, two continents, two cities (NYC and Ithaca, where I teach), between the West and the East, between being an artist and being a teacher, etc.

I am now used to hyphenated identities, and I learned to enjoy writing in a second language because it feeds my persistent curiosity and joy of learning/discovery.

To give you a little history of my artistic career, for the record: I started as a poet, writing in Romanian, publishing three books of poetry. In the late ’90s, a Romanian critic labeled me “the tough poetess-playwright at the border between millennia.” Another hyphen that defines me. When my dramatic poem Outcast was performed in Paris at Théâtre Gérard-Philipe in 1998, I was considering myself a poet, but the French colleagues called me a playwright. So I started to believe it. J

I went to Germany to study playwriting in English with David Harrower and Phyllis Nagy, at the Summer International Theatre Academy. Then I went back to Romania and won the UNITER (Romanian Theatre Guild) Best Play of the Year Award for my new play The Inflatable Apocalypse. I officially became a playwright.

Of course, it is a different “animal” to write in English for U.S. audiences. My playwriting has changed. In Romania, I used to write absurdist plays with feminist, sexual, revolutionary, and anti-consumerism undertones. In the US, I am more concerned with identity issues, immigration, and the reality of being a global foreigner, an “alien”, who works hard to feel that she belongs, that she found her home . . .

I wrote Aliens with Extraordinary Skills in English as a writer-in-residence for Women’s Project in 2008. “Alien” is a word impossible to translate into other languages while maintaining all its meanings: foreigner, extraterrestrial, immigrant . . . When the play got produced in Mexico City at Teatro La Capilla (after successful runs off-Broadway at Women’s Project, and regionally), in Spanish, under the title Inmigrantes con Habilidades Extraordinarias, I noticed different things that were relevant and impactful for Mexican audiences. When the play was produced at the Odeon Theatre in Bucharest, in Romanian, under the title Clown Visa, other aspects of the characters and storyline resonated with the Romanian audiences. While there is always a core of the play that stays the same for spectators everywhere, the nuances of the reception are different in the US, Mexico, Romania, or France, as people resonate to their own historical, social, political, and personal references.

I love to engage with various global issues and to understand different cultures – if I had more than one life, I would start to write in Spanish now, in French in 10 years, in Arabic in 20, and in Chinese in 30 . . .

CM: What did it mean for you to adapt to a foreign theatre production system? How is success defined in the U.S. theater scene, and how can a playwright coming from another culture have success here? Which are the advantages and the disadvantages of the immigrant playwright in the U.S.?

SS: “Success” is defined by everyone in a different way – I learned that in the MFA program in Dramatic Writing at NYU. For me, “success” means any production of one of my plays, and having the time and energy to write new plays on relevant topics I care about.

I think that the role of the playwright in contemporary society is to respond to the spirit and the issues of our time, to question the unquestionable, to address the difficult topics, to challenge the taboos, to subvert the mainstream power, and to never provide easy answers to stereotypical questions. That’s a success!

So I guess there are also advantages of being an immigrant playwright because you can draw from two (or more) cultures when you write a play. Plus, there is always something adventurous, outside-the-box, and envelope-pushing in the creativity of an immigrant playwright. We are restless, even when we’re not so young anymore.

In most of my plays I explore the ways in which the American Dream can turn into a nightmare at any given moment, but also strategies for survival through love, friendship, and human connection. George Bernard Shaw is credited with saying “if you tell people the truth, you better make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you”. I am trying to do that – spice things up with humor and playfulness, employ a theatricality that comes from the Romanian folkloric wisdom: one eye laughs and one eye cries.

I founded Immigrants Artists and Scholars in New York (IASNY), and we have an annual event, NEW YORK WITH AN ACCENT, at the Nuyorican Poets Café and other venues, showcasing immigrant artists: poets, playwrights, musicians, dancers, filmmakers, interdisciplinary/performance artists, etc. Unfortunately, I haven’t had time to do much for IASNY lately, as I have been extremely busy teaching full time at Ithaca College, as an associate professor of Playwriting and Contemporary Theatre, and mentoring/supporting our students. Passing my knowledge to young generations is important for me too.

I got my MA in Performance Studies and MFA in Dramatic Writing from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, and I enjoyed being a student again, after having an artistic career and professional recognition as a writer in Romania. I rarely say no to a good challenge and new beginnings . . .

However, I still like the rigor of developing a play in a process that makes it stronger and stronger; I love to work with US actors and a director towards the production of a play. There is such specificity/attention to details in terms of character, language, dramatic structure/arc/journey . . . This process is very helpful and rewarding for a playwright like me, who moved into the English language in her early 30s . . . I care about the patterns of speech for each character, I love every little word that I add in a monologue or a line, and it must be absolutely right for the character and the dramatic situation.

I am grateful to organizations like The Lark, New York Theatre Workshop, The New Group, EST, Women’s Project, La MaMa, East Coast Artists, The Cherry, Civic Ensemble, that helped me develop my craft and my vision in the last 17 and a half years, since I arrived in New York.

One could say that I am a 17-year-old American playwright now.

I will turn 18 this summer and hopefully become major.

CM: Are you writing what is expected of you, or do you take total freedom in choosing your themes? Is being commissioned to write a play a big part of your work?

SS: A commission doesn’t mean that a producer or a theatre is imposing a theme on your play. It just means that they are interested in you as a playwright, and are invested in supporting your new play. The commission also means that the new play development process will be structured, you will get useful feedback, and you will have the opportunity to workshop the play with professional actors and do rewrites that will make it better. Sometimes, the theatre chooses or commits to also produce your play. Those are happy times, of course.

I would love to have more and better-paid commissions to write my plays – who wouldn’t? I generally need to work with actors, a director and get meaningful feedback as I develop a new play.

Gone are the days when a playwright completes a play in her “ivory attic” and sends it to theatres, waiting to be picked. I would say that workshopping a new play is an integral part of the process that leads to production.

CM: How much are the themes you choose to write about connected to the multicultural aspects of your life?

SS: I am a playwright with multiple Balkan roots and a US-born grandmother, Olimpia Vanghele (Dima), who was an American citizen living in Romania. I was raised in a multicultural family. So, yes, my themes are rooted in the multicultural aspects of my life, and generally in theatrical hybridity that might be connected to the immigrant experience too.

In many of my American plays, I have scenes or choruses that take place in chatrooms, on Craigslist, Facebook, etc. I sometimes use spoken emojis and they are lots of fun for audiences and actors. In all my devised theatre pieces there is some internet forum or cyber-chorus of text messages and emails: E-dating; Riots; Back to Ithaca: A Contemporary Odyssey (based on interviews with Ithaca veterans); The Others (about microaggressions on college campuses), etc.

In my 2000 Romanian play, The Inflatable Apocalypse, I had “commercial breaks” and a postmodern nonlinear structure that intersected different narratives.

Maybe because I was in the streets, as an idealist college student, during the Romanian revolution in December 1989, and then I worked as a journalist in the newly created free press, I still believe in the revolutionary writer – the writer who’s always on the barricades, fighting for the underdogs, pushing the borders of human knowledge and the understanding of The Others.

My first assignment as a journalist in the early ’90s, in Bucharest, was to write about the pulling down of Lenin’s statue from its pedestal. Then I had to interview the first woman prime minister of Turkey. Those experiences informed my playwriting much later.

In 2006, in NYC, I wrote Lenin’s Shoe, a play about the trauma of the Past “pulling you down” from the reality of the Present. It seems that I needed time and distance (personal, geographical, cultural) to better understand my own past and HERSTORY, and to explore them in my writing.

In Waxing West, which won the 2007 New York Innovative Theatre Award for Outstanding Play, I was finally able to have a character, Daniela, who deals with the memories of the 1989 revolution, as she is trying to make a life for herself in NYC. I dramatized Daniela’s inner conflict: she is haunted by dictator Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena, who appear to her as vaudevillian vampires.

In Aliens with Extraordinary Skills, Nadia, the protagonist from Moldova, is harassed by imaginary immigration officers, symbolizing her fears due to her undocumented status.

I always try to find a theatrical way to explore concepts that go beyond psychological realism. I guess this is happening not only because of my Eastern European / Balkan heritage but also because, as a writer-in-residence for Richard Schechner (YokastaS Redux; Timbuktu) in my first years in the US, I learned to write in English with an enhanced sense of the performative possibilities of a theatre piece.

Even my recent play, What Happens Next, a futuristic “Waiting for Godette”, with two mysterious women in a dystopian white room (commissioned and produced by The Cherry Arts), engages with multimedia performativity and innovative playwriting techniques that might remind people of the Netflix series Black Mirror.

Saviana Stănescu. Photo by Jody Cristopherson

CM: Into how many languages have your plays have been translated, and which are these? What is your approach when it comes to the translation of your plays: how closely do you supervise this process (or not?)

SS: Hmmm, I haven’t really counted them, I don’t know; I am not involved in the process of translation, generally. I only hear about a production abroad from one of the members of the creative team, from my agent, from Samuel French – my publisher and licensing agent for some of the plays – or just randomly, from the internet, or a Google alert.

I know that there was a recent production of Aliens with Extraordinary Skills in Turkey, for instance, but I didn’t see it.

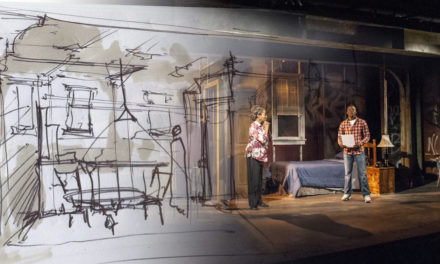

However, when Aliens with Extraordinary Skills was produced in Mexico City, I participated actively in the process of translating the play, because the Mexican team got a grant to invite me for 10 days to develop the Mexican version of the play with the director and the actors. After that, I went back to Mexico after a few months to see the production at Teatro la Capilla. Another great experience was when the Odeon Theatre in Bucharest invited me for the whole rehearsal process for the production of Aliens with Extraordinary Skills (Viza de Clown), and it was really wonderful to work with the director, the actors, the designer, while honing the script for the Romanian production (trying to find better references and phrases, the specific humor in Romanian, etc.). I would love to be more present for rehearsals/development abroad.

CM: How would you define a favorable context for playwriting to thrive? Where in the world did you find the most favorable of such contexts, and which aspects of it were more important for you? What do you think the Romanian theatre system lacks in this sense (if anything)?

SS: As I said, I think that a playwright needs to respond to the hot issues of the society she lives in, to have an impactful voice, and to play an active role in triggering social change. When I left Romania in 2001, writers were still public intellectuals; their opinions mattered on a political and cultural level. We were interviewed by TV channels and asked for our perspectives on various matters, we wrote columns in the main newspapers. We had a voice as individuals and citizen-artists. To a certain extent, that is still the case in Eastern Europe, although I think that the role of the writer in the society has diminished compared with the ’80s and the ’90s when intellectuals were stars, celebrities.

US theatre is focused on the playwright and the new play development/production, but the playwrights here don’t seem to have a strong voice in society as public intellectuals. Celebrities are Hollywood actors, politicians, TV talk-show hosts . . .

Many US playwrights struggle to make ends meet; they have to teach or write for TV in order to pay the bills. And those are the good options – others just have frustrating 9–5-day jobs. It’s hard to have any public clout in those circumstances. Your focus is on survival as an artist; you still need to write what you have to write and tell the stories you need to tell. Luckily there are a few significant grants, awards, and fellowships that help some playwrights continue doing their work, so for folks who got enough mainstream recognition, life gets a little easier materially.

But I do like the fact that American theatre is more playwright-oriented than the Eastern European theatre, which is still director-centered. Many European directors look at a play as a blueprint for a production, so they tend to make cuts and edits and apply a directorial concept to the play. The result can nevertheless be a beautiful show.

So, I guess, at this point I try to adjust my expectations to the team I’m working with, knowing that in Romania and continental Europe, my play might suffer or benefit from the directorial vision. J The directors I enjoy working with are artists who are doing justice to my writing, respect the playwright’s vision while finding an innovative way to stage my play. And many good directors tend to do that.

I am also happy that I have been able to open US doors for other Romanian playwrights. As a TCG fellow, Director of International Exchange, and Director of Eastern European Exchange for The Lark Play Development Center in New York (2005–2010), I co-created the American-Romanian Theatre Exchange (ARTE) with the Odeon Theatre in Bucharest and the Transylvania Playwriting Camp with the University of Arts in Târgu Mureș.

Together with significant American playwrights (Doug Wright, Rajiv Joseph, Tanya Barfield, Michael Bradford, Ken Urban, Kelly Stuart, Brian Dykstra, etc.), we traveled to Romania, conducted playwriting workshops, and had the opportunity to see a new generation of Romanian playwrights grow and gain visibility. I still think that the best strategy to thrive for us, artists/playwrights – in the US, Romania, everywhere – is to support each other and raise our voices through our work. To be more revolutionary than ever.

Actually – as you know, Cristina – I plan to spend my sabbatical semester (Fall 2019) in Romania, developing a play rooted in the December 1989 events: The Revolution Project. It’s time for the “prodigal daughter” to go back and look at what happened 30 years ago, during the fall of the Iron Curtain and Ceaușescu’s regime. To summon a fresh perspective with her young and old Romanian-American eyes.

Let’s do it. Let’s open that curtain!

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Cristina Modreanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.