Although they are unlikely to be exhibited in India, auteur Sankar Venkateswaran’s recent exploits on the German stage present an intriguing extension to his impressive oeuvre, almost a decade after his breakout works — Quick Death and The Elephant Project — established him as the voice of his generation. On May 26, he opened his latest opus, Indika, at the Munich Volkstheater, his second outing at that venue in as many years, after last year’s Tage der Dunkelheit (Days of Darkness), based on the final moments of the battle of Kurukshetra. Both plays feature German actors enacting episodes from India’s classical era.

In Indika, Venkateswaran, in collusion with the Volkstheater’s resident dramaturge, Nikolai Ulbricht, takes up a particularly fraught chapter in India’s history — the expansion of the Maurya empire under Chandragupta. By 320 BCE, vast tracts of the Indian subcontinent came under the ambit of a centralized state, on which was unleashed the realpolitik of statecraft by Machiavellian royal advisor Kautilya, with dehumanizing consequences for humankind. “Chandragupta’s political system did not work,” said Venkateswaran in the German newspaper, Abendzeitung, “He left everything behind, his palace, his city, and went on a 3000-mile-long hike to the south, eventually starving to death.” Although he has extracted just a lyrical sliver of material from the epoch at his disposal, there is no denying the deep-seated political undertones that carry resonances to this day, and remind us of the ideological conflicts that we are all jousting with in these uncertain times.

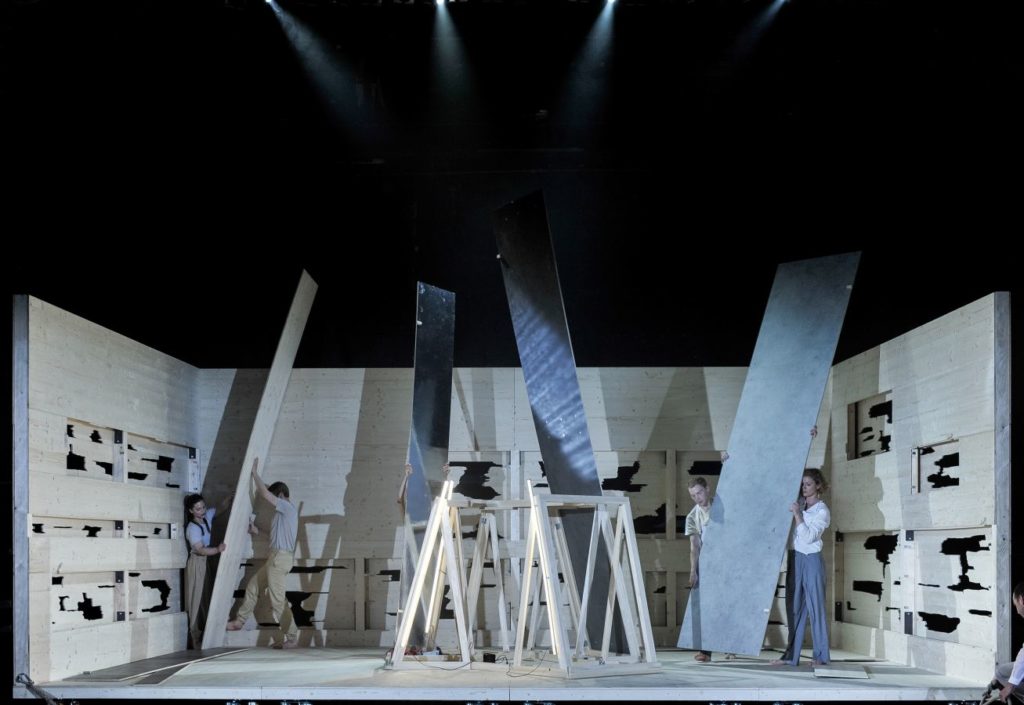

Luise Deborah Daberkow, Silas Breiding, Jakob Immervoll, Magdalena Wiedenhofer in Indika. Photo: Arno Declair

Bare Basics

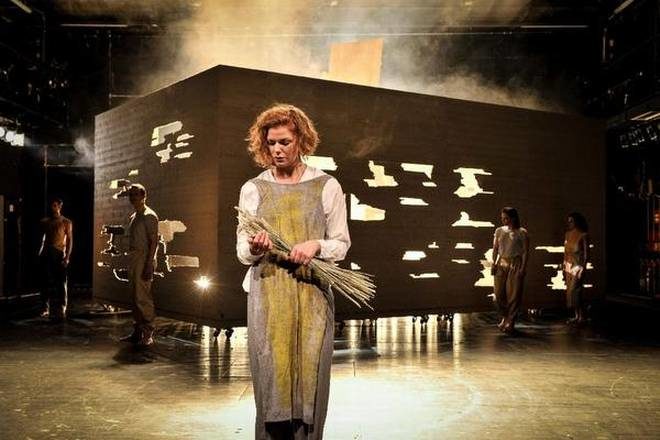

Characteristically, the director has worked with just seven actors, and very sparse text, with extended non-verbal sequences that powerfully make use of measured movement and an unsettling silence. This is a hallmark of Venkateswaran’s works, as he explains, in various interviews, “It is about poetry and clarity, without being textual: fewer words, more bodies. Slowing down allows us to view things clearly so that you can rebel against the flow and pace of the present.” Pascal Fligg, the 34-year-old who plays Kautilya, is the only one assigned a singular part, with the others flitting in and out of characters. Apart from Fligg, who played Duryodhana in Tage der Dunkelheit, Venkateswaran has been reunited with other collaborators from his previous work — actors Mehmet Sözer and Magdalena Wiedenhofer, and stage designer, Ran Chai Bar-zvi, a graduate of the Berlin Weissensee School of Art, who was born and raised in Jerusalem.

The Abendzeitung correspondent, Michael Stadler, provides an interesting account of Bar-zvi’s and Venkateswaran’s collaboration, “From the walls of a large open box, Sözer (as Chandragupta) hacks out individual wood panels, plonking them on the deck, loudly, as if a battle were raging. Other actors pile the pieces into a kind of sculpture that represents a new state structure. On ropes, a profusely perspiring Sözer hauls the contraption forward, like the full-bodied leader he is.” This pièce de résistance set-piece symbolizes the brawn of political enterprise as embodied by the sun-kissed Chandragupta, the brain being, of course, Kautilya’s. For theatre aficionados, especially those stationed at a remote vantage like us, Bar-zvi has posted clips of his avant-garde assemblage on Instagram. Another multicultural influence on the play is the award-winning Chinese composer, Lin Wang, whose operas and chamber pieces have frequently been performed in Germany.

Magdalena Wiedenhofer, Luise Deborah Daberkow, Jakob Immervoll, Mehmet Sözer in Indika. Photo: Arno Declair

Wielding Outcomes

The reviews in the German press have talked about the play being warmly received by the first audience the production had. In the regional daily, Donaukurier, Hannes Macher writes glowingly of Venkateswaran’s visual aesthetic which, “strikingly sets the stage to showcase the power of despots across continents and centuries. The actors emerge from an amorphous mass in slow synchronous movements, gradually picking up the pace, to ultimately erupt into a convulsive ecstasy.” Christoph Leibold from Deutschlandfunk Kultur, a culture-oriented radio station, is less generous, “One wonders if an Indian has really staged this cliché-ridden evening with its pantomime imprints, stylized gestures and best-of-Asia sound. Perhaps it is because of the mostly white local actors who, in their bright linen costumes, look more like the awkward participants of a Yoga video.” Alexander Altmann in the Münchner Merkur sums the play up as such, “With this contemporary dance-like staging, the director succeeds in creating a perhaps too catchy, but wonderfully imaginative, stage parabola about the mechanisms of power and the damage inflicted on rulers as well as the ruled.” Finally, stage critic Wolf Banitzki writes, “It was a terrific evening of theatre, in which an eternal dilemma of humanity unfolded on the basis of a simple historical episode without being didactic. In a time when ‘simple answers’ are deemed suspicious, because they are so often employed by populists, the theatre provides such simple answers, which are very true, nevertheless.”

There are four more shows scheduled for Indika in June and July at the Volkstheater. They should provide the turf for Venkateswaran to more expansively realize the full potential of this cross-cultural artistic experiment.

Quotes have been paraphrased from German.

This article was originally published on The Hindu.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.