In the Italian region of Siena, perched on top of a hill, sits the sleepy village of Montichiello. The winding roads leading there are lined with Tuscan Cypress trees; the cobbled streets wedged between medieval housing. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this typically exquisite Tuscan village struck a chord with filmmakers Jeff Malmberg and Christine Shellen, who were enjoying their honeymoon in the picturesque corner of Italy.

“The other towns were very touristy, like something out of Under the Tuscan Sun. This town felt like a real town. There weren’t all the little shops. The only thing that was open was an artist studio.”

That artist studio is home to Andrea Cresti, an enigmatic eccentric who runs the village theatre company.

“Around the late 50s and early 60s the government disbanded the farming system. Montechiello was headed the same way and residents were very concerned.” – Christine Shellen

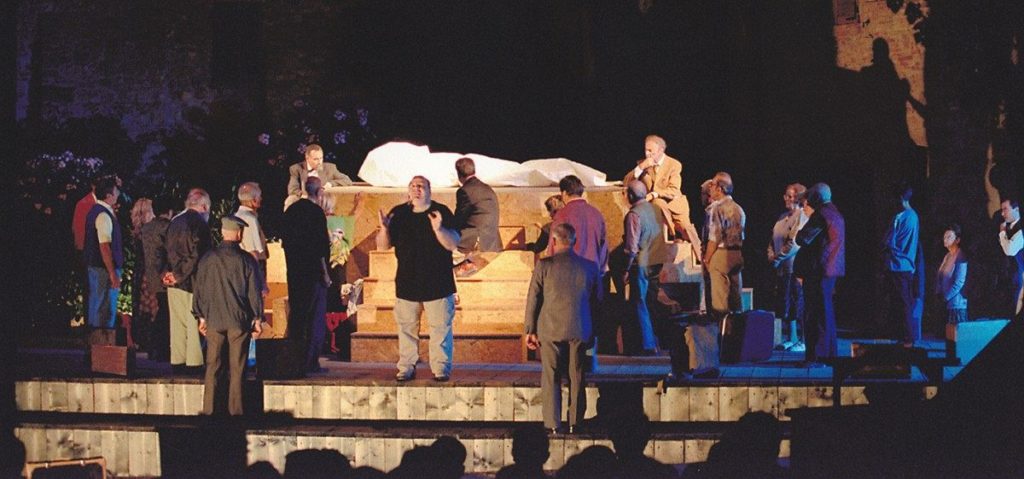

Il Teatro Povero, translating as the poor theatre, turned 50 last year. And it holds a very unique tradition. Nearly every resident of Montichiello is a member, and once a year they all perform as themselves in a play. Malmberg and Shellen were so captivated by the unique village they stayed for six months. Only to find its tradition threatened by the global financial crisis.

Formed out of protest

Before the formation of the village’s theatre company, Montechiello was a forgotten slice of Tuscany. The village’s biggest claim to fame was an uprising against Nazi invaders – a feat that elder residents frequently bring up in Spettacolo, Malmberg and Shellen’s new documentary about the town. However, Il Teatro Povero is now the village’s main attraction. The theatre was formed in the 1960s as a reaction to the destruction of Montichiello’s agricultural way of life.

“1950s Tuscany… was just like a medieval farming culture,” explains Shellen. “Around the late 50s and early 60s that all changed and the government disbanded the farming system there. Montechiello was headed the same way and residents were very concerned. “They felt that the government didn’t care about the small towns, so they wanted to send a message. They decided to create this theatre and tell their story.”

For half a century villagers have gathered in the piazza to discuss, debate and argue. Malmberg notes how the theatre group has become important to the life of the village. “I think it’s proven to be essential to them, and one of the things I was always interested in was what happens when you make art the centre of your life as a group. “I think you see it in the way that they talk and the way they argue with each other. It’s very advanced and artistic.”

‘They all participate in their own way’

Ranging from six to 90 in age, nearly all residents of Montichiello take part in the annual production. “Some may not take part in coming to the meetings and performing on stage,” says Malmberg. “[But] people who can’t participate due to work constraints or illness will purchase tickets, they all participate in their own way.”

Not every resident is so enthusiastic about the theatre company being at the heart of goings-on in the village, however. “There was a cranky older man in town who got really tired of their theatre at one point because they were practicing right outside his window,” notes Shellen. Once, he threatened them with a gun. “But yeah, pretty much the whole village partakes in some form. Minus one cranky old man.”

A bleak outlook?

In one of Spettacolo’s most significant moments, an announcement is made that funding for the theatre company has been cut – leaving the village’s future in doubt.

Now, globalisation and a bleak financial outlook have contributed to a shift in village attitudes.

“They’re incredibly hardy people. Back in the ’60s and during World War Two they explain how their backs were against the wall, but they survived.” – Jeff Malmberg

“When they first started, theatre was their principal means of entertainment,” explains Malmberg. “They’d meet in the square at 9.30 and argue with one another. “I think it’s a tribute to their theatrical tradition that it is still running, but they now live in an entirely different world due to technology. Funnily enough, the end of the world is their subject when we film them.”

Shellen suggests that Montichiello’s movement from tradition might be reflective of the world as a whole. “The conditions that caused them to start the theatre company in the first place have become worse lately because of the global economic crisis. Small towns all over the world are having trouble continuing. There aren’t any jobs for kids worldwide and the same thing is happening in Montechiello. It’s like a microcosm for the entire world.”

Despite the cuts in funding and the threat to the end of Il Teatro Povero, Malmberg suggests that those at the heart of the company are as resilient as ever. “They’re incredibly hardy people. Back in the ’60s and during World War Two they explain how their backs were against the wall, but they survived. They’re continuing with a play this summer, and hopefully beyond.”

Spettacolo is screening at Sheffield Doc Fest between June 9 and June 13

This article was originally published on iNews.co.uk. Reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Finlay Greig.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.