Veridiana Zurita pleads for more reciprocity between artists and curators.

The relationship between artist and curator has never been entirely without friction. In times where neoliberal working conditions put both sides under pressure, it can even go completely wrong. Based on her experience with Kunstencentrum Vooruit, Veridiana Zurita advocates in this opinion for a collaboration in which reciprocity and conversation play a central role. She puts the psychiatric clinic La Borde forward as a good practice.

This text was supposed to start with “Once upon a time.” It was supposed to turn a contemporary case into a short story from long ago, like a fairy tale almost, with its archetypal relations, monsters, creatures, and heroes. In it, an artist and two curators would become the folk characters of the art world. The artist would wake up one morning and, as she checked her emails before doing anything else, she would be swept aside by curators. A personal case would be generalized as the cliché of a power dynamic between curators and artists where the former pick and the latter are picked, invested in, discharged and replaced.

By calling out names I aim to look at this personal–and yet quite common–case outside of the realm of gossip. I hope this story can lead to a broader reflection on the often troubling collaborations between institutions, curators, and artists. It might wake the different parties from their naturalized hierarchies and stimulate the imagination of more horizontal alliances.

A Story

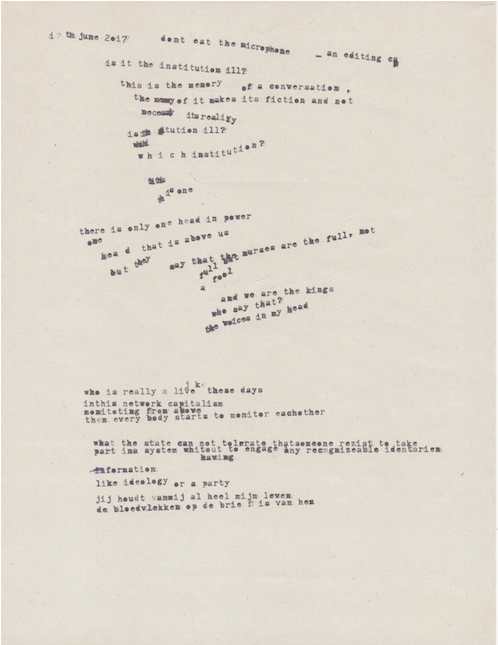

In 2015 Matthieu Goeury introduced me to Maarten Soete, the main curator at the time of the STADSRESIDENTEN in the Vooruit Arts Centre in Ghent. The project Don’t Eat The Microphone (DETM), which I initiated in 2014 with psychoanalyst Petra Van Dyck, was to continue in collaboration with the Ghent Arts Centre. At the time, this institution was going through a major crisis that shook the ground of those working for it. People were fired, others left frustrated, and some were replaced. Our residency happened during the 2015/2016 season, which was when Matthieu and Maarten left the Vooruit. Marieke de Munck was tasked with curating and coordinating the residency and with it, inherited a programme she had not entirely chosen and under precarious financial circumstances. The season passed, the residency happened and Marieke invited us to continue the project during the next season. A series of meetings were set up to put things into perspective. We all seemed to be on the same track.

On 29 January 2017, I got a casual email from Marieke abruptly ending the residency of DETM. In few words and an uncompromising tone, she swept aside a project as if there was no shared history. Her move exposed a fragile ground where artists, curators, and institutions don’t seem to nourish a “shared endeavor.” In dialogue with Matthieu, who had returned to the Vooruit at some point in 2016, they decided that the project could no longer be continued under their care.

Different reasons were subsequently given for the sudden break.

“We have less budget than we thought,” Marieke claimed.

“We are making radical changes to the program,” Matthieu continued, “and want to bring in new artists.”

We were put before an absolute and unilateral decision in which we had no say:

“Unfortunately we have decided that the residency could not be continued,” to which was added the rather wry message, “Hopefully we can collaborate soon.”

Such a one-sided decision-making process is a symptom not only of how dischargeable and replaceable artistic practices seem to be but also and especially of the discrepancy between institutional discourse and practice. Vooruit promotes itself as a progressive organization, capitalizing concepts like Horizontality, Durability, Participation, Research, Social Engagement, and Responsibility to describe the STADSRESIDENTEN residency we were taking part in, a residency that aimed to support artists working in the city with its inhabitants and at specific locations.

Management and Resistance

DETM is an artistic project that takes place in the garden of the Psychiatric Centre Dr. Guislain in Ghent. From the beginning, it was never supposed to be a show and as yet it’s not a project that is easy to programme. During our residency at Vooruit, it was clear that there was nothing to watch but rather a situation to take part in. The publicity surrounding the project was rather muted since the scale of participation could compromise the intensity of the work. No tickets could be sold but scheduled visits could be made for those interested in engaging. These could be the real reasons why the project lost its support.

Vooruit’s recently revised institutional status could mean a greater commitment to the continuity of artistic projects, especially those showing responsibility towards specific social contexts. The Ghent Arts Centre was officially recognized as a Flemish Art Institute (Vlaamse Kunstinstelling), which means that it has a bigger budget to spend, that the continuity of its institutional existence is ensured, and last but not least, that it is expected to carry out all of the institutional functions listed in the Arts Decree, namely Production, Presentation, Reflection, Participation, and Development.

“The pressure to develop an entrepreneurial self who has to transform and adapt continuously, to run an impossibly busy agenda and to engage, often only superficially, with a variety of arts practices, is a common ground between curators and artists.”

It is highly likely that curators of big institutions are drawn into structures that are far more complex than artists could ever understand. However, in the wider arts field, the pressure to develop an entrepreneurial self who has to transform and adapt continuously, to run an impossibly busy agenda and to engage, often only superficially, with a variety of arts practices, is a common ground between curators and artists. Within the institution, both artists and curators have to find their way in the organizational complexity of that machine of cultural production. It’s a shared battle.

Yet, what became clear to me is that very little effort was made to resist the alienated working conditions and production values both artists and curators are subjected to in times of neo-liberal precarization. When curators are the ones entitled to end a collaboration and artists are left out of such decision-making, an opaque hierarchy overshadows negotiation, dialogue, and mutual agency. Self-management then remains the only survival weapon. Artists are expected to swiftly find support elsewhere while these dominant protocols of cultural production exclude these kinds of artistic work, these work methods, and subjectivities that fail to meet its criteria.

Don’t Eat The Microphone © Veridiana Zurita

The Institution is Ill

One afternoon, while we were setting up DETM in the garden of the Psychiatric Centre Dr. Guislain, a patient arrived. There were microphones, wires, coffee, birds, vinyls, cigarettes, keyboards, a dog, patients, trees, texts, artists, therapists, a rusty guitar, psychotics, neurotics, plastic, stones and a few typewriters. He had a restless face, as if he had woken up from a bad dream. That morning, he told us, he got the uncanny news that his cure now had a deadline. Back then, psychiatric hospitals had started to implement an agenda by which cure has to be sped up in order to guarantee a more rotational routine of admissions and discharges of patients in the institution. One might receive this news as positive since no one wants to be locked up.

However, when the acceleration of cure is measured by what psychiatric hospitals have started to call “empty beds,” such news might not be as positive as may seem. Since neo-liberal policies were being sharpened everywhere in the Belgian social system, “empty beds” started to appear as an expression used alongside the mantra “measuring is knowing” (meten is weten) echoing in the corridors of psychiatric institutions. “Empty beds” would guarantee efficiency in the turnover inside psychiatric hospitals by speeding up the curing process. Beds had to be emptied in order to be occupied as soon as possible. In order for such a machine to work, systems of measuring cure had to become more efficient, according to the economic criteria of the healthcare system.

“Curating and curing can both become instruments of measurement instead of practices of relation. The notion of cure as the unilateral care of the other (whether the patient or the artist) needs to be reimagined.”

The patient, troubled by the hospital’s new agenda, joined the DETM session and was asked, “Is the institution ill?” He grabbed a mic and gave us the following diagnosis: “There is a big, omnipotent head. It works from the top down. No matter how those below it engage with the process inside the institution, its decision is absolute. It has the power to deal with money but no time to engage with the place where the money is invested. It is the boss. It doesn’t matter if doctors or nurses try to inform him about the process of the patients, his decision-making won’t change with regard to such processes. Everyone is isolated from one another: the boss from the staff, the staff from the patients, the patients from other patients. We lock ourselves inside the room. Isolated and individualized. Everyone surveils one another. Everyone denounces what’s deviant in order to please power. The boss surveils the doctors, the doctors surveil the therapists, the therapists surveil the nurses, the nurses surveil the patients, the patients surveil one another. Everybody is gossiping. I feel hollow, I can’t feel the other, and when I want to hug the other I fear vulnerability.”

The narrative given by the patient seemed to diagnose the illness of institutions co-opted by neo-liberal discourses. When economic efficiency becomes the ultimate goal, care is subjected to a certain regime of measurement where the managerial segmentation of individual skills within an institutional framework leads to social alienation. In periods of instability, the other becomes a threat. The fear of the other, the fear of vulnerability is the trigger for institutions to invest in measures that guarantee surveillance, protection, and isolation.

What is programmable in the cultural institution can become the equivalent measure of what’s curable in the psychiatric one. Curating and curing can both become instruments of measurement instead of practices of relation. The notion of cure as the unilateral care of the other (whether the patient or the artist) needs to be reimagined.

What Institutions Could Learn From La Borde

Institutional Psychotherapy (IP) has been a significant practice challenging the hierarchies and social segmentation within psychiatric institutions. One cannot reimagine an institution without knowing what IP has been experimenting with since the 1950s. IP was a psychiatric reform that began in a small town in central France called Saint-Alban. By experimenting with forms of conviviality in the psychiatric hospital, François Tosquelles resisted the tendencies of that time when homogenization and segregation characterized the treatment of the mentally ill. In 1953 Jean Oury (who was one of the first residents at Saint-Alban) founded the Clinic of La Borde in Cour-Cheverny where IP was fervently practiced.

From the start of DETM, IP, and La Borde have been key references for Petra Van Dyck and myself in the implementation of the project. One of the main structural changes initiated by Oury at La Borde was that it welcomed philosophers, artists, writers, and film-makers alongside medical personnel. The hospital was no longer an institution of social segregation where authoritarian, oppressive and stagnant structures prevailed, but rather a place to “imagine a philosophy, a social theory, and a practice of everyday life” (Robcis 2017). [1] Responsibilities were shared and social structures constantly rethought, reworked and remapped by doctors, nurses, and patients. Cooking, cleaning, answering the phone or organizing medication were practices that involved a common effort. According to Oury, the hospital with its accumulations of regulations was ill. It had to be treated in order to treat. La Borde thus became a place of an invention for a new, horizontal institutional politics.

Despite the fact that La Borde itself wasn’t immune to the effects of neo-liberal policies and was fundamentally changed in recent years by the French healthcare system, it still challenges the common notion that institutions can’t be thought of outside of centralized power, stagnant hierarchies, and social segmentation. The (differing) efforts of Tosquelles and Oury keep on opening up a whole understanding of how people can do politics through the practices of everyday life. Healthy institutions are eternal works in progress, which need the participation, agency, and responsibility of all those involved.

“Healthy institutions are eternal works in progress, which need the participation, agency and responsibility of all those involved.”

Politics as a practice of daily life is continuously threatened by the co-optation of economic efficiency. According to philosopher and activist Felix Guattari, who was deeply involved in La Borde, “we are all always more or less co-opted. Ultimately, it’s about politics and micropolitics, not purity.” [2] Following his words, there is probably no such a thing as “liberation” from a system of co-optation but rather zones of action where communication among social roles can happen. It’s as if one could make holes in the materiality of social segmentation, join with and resist the hegemonic discourses, production of values, subjectivities and ways of relating.

Alienated from each other’s processes, socially isolated by the systems of artistic production, made anxious by the fear of losing their job, and under the threat of institutional measurability, curators and artists seem to neglect practices of conversation, immersing themselves in the inertia of self-sufficiency while becoming islands of productivity. In order to de-alienate such a work system, curators and artists should join forces to think about and make a joint project. A project which can overcome the paradigms of selection and production (illness and cure). For that sort of alliance to happen, a practice of mutual care, in which the curator curates the artist’s project as much as the artist curates the curator’s reading of the project, is needed.

REACTION VOORUIT

Vooruit acknowledges the feelings and feedback of Veridiana Zurita. The article was discussed by the different teams involved as we consider artist feedback on the working of Vooruit of the utmost importance. We look forward to discussing the situation further with Veridiana Zurita during our next collaboration with Michiel Vandevelde and his project Precarious Pavillions, of which she is part of with the project DETM.

1 Institutional Psychotherapy in France: An Interview with Camille Robcis (2017), www.bbk.ac.uk/hiddenpersuaders/blog/robcis-interview

2 Guattari, Felix en Sylvère Lotringer (ed.), Soft Subversions. Texts and Interviews 1977–1985, The MIT Press, Boston, 1996

This article first appeared on Etcetera on June 18, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

Author: Veridiana Zurita

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Veridiana Zurita.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.