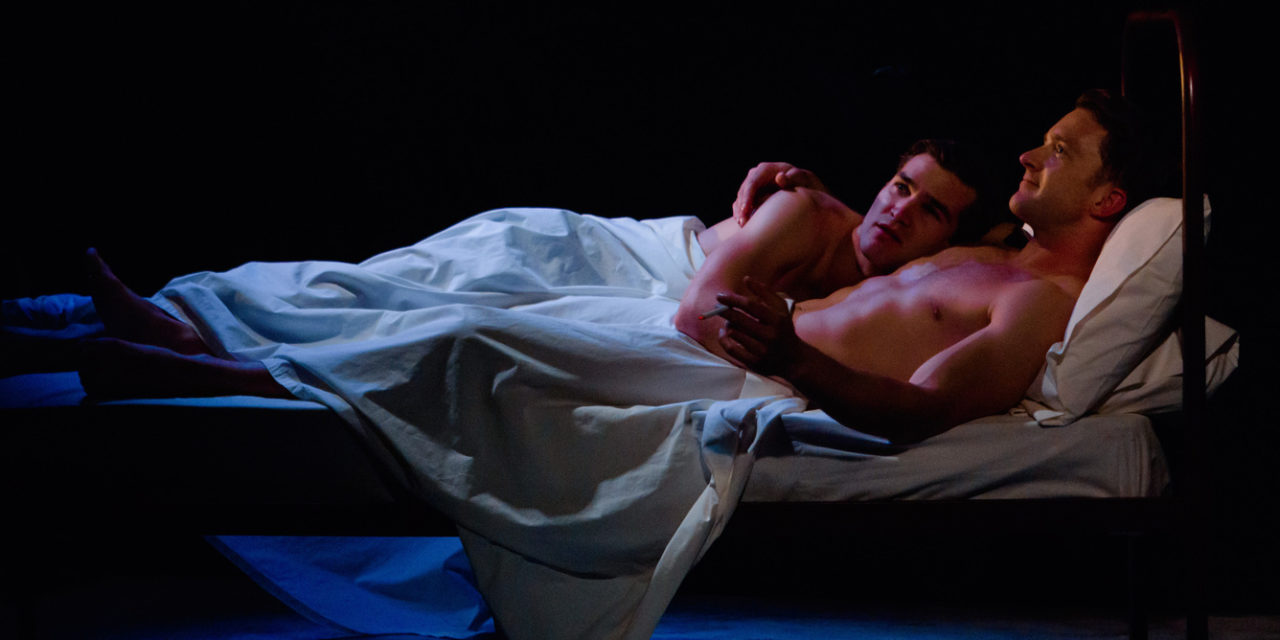

Only Heaven Knows, a musical about a young Melbourne man who discovers the queer delights of homosexual desire, unexpected intimacies and gender transgressions in Sydney’s Kings Cross in the 1940s, has been revived in its thirtieth anniversary year at the Hayes Theatre in Elizabeth Bay. The director Shaun Rennie had reservations about staging a late 1980s musical about the 1940s, wondering if it would be a “museum piece.”

It’s not, and it remains highly relevant today. It’s also a great night at the theatre, full of belly laughs and show-stealing numbers that pack some emotional punch. There were quite a few audience members wiping away tears after a gut-wrenching second act. Indeed, rendering the past visible is rarely a simple trip down memory lane.

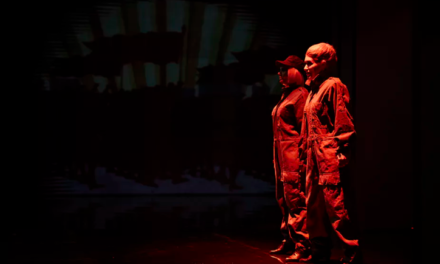

The musical opens with a thumping number from the ghost of a cross-dressing performer who seems to meld together the historical experiences of Harry Foy and Lea Sonia. Both were killed in the 1940s, Sonia by a tram on Oxford Street, and Foy in an act of gender violence after a show.

She evokes a lost queer world and introduces us to Tim, a doe-eyed 17-year old, who leaves an unsupportive family in Melbourne to arrive in Kings Cross in 1944. In bohemian Kings Cross, Tim forges a queer family and discovers the world in which gender and sexuality have been thrown upside down. Same-sex desire, cross-dressing and other forms of queer delight, while still policed and prohibited, thrive.

Queer in the Cross

During the 1920s, the Cross became the centre of bohemian life in Sydney. The construction of smaller and cheaper dwellings from the 1920s meant that Kings Cross and Potts Point became one of the most densely populated regions in Sydney. In 1939, The Sydney Morning Herald noted,

The Bohemians and the underworld emerge from their lairs at about eight o’clock when the blanket of the dark encourages them to take the air. Certain cafés are recognised as virtually clubs for different grades of moon-worshippers.

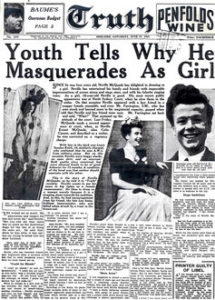

World War II only exacerbated these transformations. Brown-outs in Sydney and Melbourne, in which street lighting was dimmed in order to prevent Japanese bombing, became powerful metaphors for uncertain and murky urban environments in which desires might find an unexpected object.Queer life was a visible part of this unruly world. Sydney historian Garry Wotherspoon suggests that the 1940s represented something of an apogee in the loosening of ideas about gender and sexuality. A rich camp underworld took shape. Parties like the Artists and Models Ball made cross-dressing and same-sex desires a normal part of this world. Tabloids like The Truth reported on these queer desires and practices with surprising regularity.

It was only a short walk for American and other military men from the Garden Island naval base in Woolloomooloo to the Cross during WWII. In the queer world of Kings Cross, slang like TBH and TBHID (“to be had” and “to be had in drink”) described the ways in which these worlds could erotically intersect.

The 1950s: the darkest decade

Only Heaven Knows draws much of its material from the world described in Jon Rose’s autobiographical novel, At the Cross, first published in London in 1961. Like many homosexual men who could afford to do so, Rose left Sydney for London in the 1950s as the queer world of Sydney seemed to fracture.

The second half of the musical moves into the mid-1950s as these queer ties strain under the cold-war intolerance of Robert Menzies’ government. These tender ties threaten to unravel as Tim looks to London to escape. His romance descends into conflict and the friendships that flourished in the 1940s come under the pressure of increasing homophobia and gender discrimination.

The vulnerability of queer lives in this decade is powerfully evoked on stage when Alan, a serviceman thrown out of the army for committing gross indecency, decides to undertake aversion therapy. This nearly kills him, both psychologically and literally. In a confronting scene, we watch this young man submit his body to electric shocks under the control of a doctor. Only Heaven Knows does a superb job of making us understand why so many men sought out this treatment in the later 1950s and 1960s. This was a climate that suggested they “were fooling themselves” if they thought that queer kinship could last.The hostile and homophobic reception of Rose’s novel in Australia showed the increasingly persecutory atmosphere in the 1950s. A reviewer in the Canberra Times argued that it is “obvious that Rose and his associates were only fooling themselves that they were really living.”

The 1980s: another rupture

Staging this production at the Hayes Theatre is doubly resonant. The musical was first staged nearby in 1987, as the gay community in Sydney was reeling from the impact of HIV/AIDs.

Public health campaigns used the grim reaper. Some politicians suggested that gay men be quarantined. Sex between men, it seemed, represented some kind of infectious threat to the nation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U219eUIZ7Qo?wmode=transparent&start=0

So the show was widely lauded in its first production for providing a story of love and friendship at a time when these queer ties were essential for survival. In the first act, the flamboyant Lana, who Tim encounters, recounts fooling a crematorium into believing he is a family member in order to take possession of the ashes of a loved one. It’s a powerful evocation of the ways in which gay lovers struggled to have their kinship acknowledged in hospitals in the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The future

Rennie suggests that Only Heaven Knows should be viewed as a reminder that “we are but the custodians of this long march towards equality … it is always two steps forwards, one step back.” And this sentiment is echoed in the staging of the final scene.

But the story being told at the Hayes Theatre this month and the context of its first production have something more complex to tell us; not least that history doesn’t move in straight lines and the past can’t be measured on a tidy progressive scale with repression at one end and liberation and equality at the other.

Only Heaven Knows evokes two of the most potent ruptures for queer life amongst men in the post-war years: the clamping down on same-sex desire in the 1950s and the trauma of HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s. Queer lives were reassembled and reforged in the midst and wake of these experiences, but they had been forever changed in unpredictable ways. Futures once-imagined became impossible, whether these futures were with departed loved ones or in social spaces that had since disappeared.

![]() As we tell heartening stories about a linear march towards equality, the lost queer world of 1940s Sydney reminds us that history is full of strange turns, detours, redirections and ruptures. We do an injustice to past queer lives if we use their experiences to tell politically tidy stories about the destination of historical progress.

As we tell heartening stories about a linear march towards equality, the lost queer world of 1940s Sydney reminds us that history is full of strange turns, detours, redirections and ruptures. We do an injustice to past queer lives if we use their experiences to tell politically tidy stories about the destination of historical progress.

Leigh Boucher is Senior Lecturer in Modern History at Macquarie University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leigh Boucher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.