John Waters called Hairspray “the only radical movie I ever made” (from Dawn Monique Williams’s program note). With all of its catchy songs, cheerful colors, and likable characters, Hairspray was easily billed as a family-friendly comedy musical in 1988. Watching the show today, audiences can experience the story in a way that’s closer to what Waters intended. Our awareness of and ability to recognize how wrong it is to discriminate based on race or body type has evolved since the 1960s, when the story takes place. Today’s audiences also have a keener sense of how important representation of all types of people, especially in art, is. These conversations are only becoming more prevalent in the current political climate. In an attempt to highlight and mitigate this, director Christopher Liam Moore chose to incorporate another type of “otherness” to this story: disability.

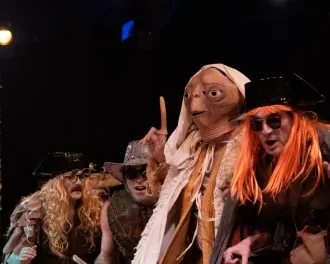

Hairspray—The Broadway Musical(2019): Ensemble. Photo by Jenny Graham, Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

In 1962 Baltimore, Maryland, Tracy Turnblad (played by Katy Geraghty) is a cheery plus- sized high schooler eager to get on to her favorite dance TV show, The Corny Collins Show. The story that follows tackles racism, body shaming, and politics through what is essentially a dance party. Amber Von Tussel (played by Leanne A. Smith) is Tracy’s nemesis and archetype of beauty for the time. Amber is also dating Tracy’s crush and the most popular guy in school, Link Larkin (played by Jonathan Luke Stevens). Throughout the play, Amber exudes white and able-bodied privilege as her mother, Velma (played by Kate Mulligan), gets her the most airtime and accolades. Fighting against social norms and the law of the day, Tracy and her friends take on pressing issues in a way that speaks to the audience without alienating or shaming them. What exemplifies this conflict the most is the interracial relationship between Penny Pingleton (played by Jenna Bainbridge) and Seaweed Stubbs (played by Christian Bufford). The couple acts as a bridge between people and politics. We can’t help but cheer loudly for these two kids and also want to caution them as Motormouth Maybelle (played by Greta Oglesby) does: “I never mind love. It’s a gift from above. But not everyone remembers that. So you two better brace yourselves for a whole lot of ugly comin’ at you from a never-ending parade of stupid.”

Two of the most striking aspects of this production were its use of spectacle and blocking to convey segregation and integration. When the show opens, it’s raining in Baltimore. People are shielding themselves under umbrellas or newspapers and are grouped together by race and ability as they navigate their morning. It’s here, in the first song, where we see the disparities between the white characters and black characters and characters with disabilities, a scene underscored by the lone and unflappably optimistic voice of Tracy.

The detention room serves as another crossroads for inclusion and exclusion. Here, we see how the high school has created “otherness” by putting kids who have broken the rules together into one separate classroom. Here, Tracy and Seaweed meet and change the course of the musical. Because of this moment, Tracy’s interest in integration is backed up by real-world experience, and her drive becomes not just a wish she has, but a cause to stand up for. We get a chance to really get to know Seaweed too, and he can’t be dismissed as a minor character any longer.

The end of the show stands in glittery contrast to its dreary beginning, and perhaps only now do we truly see what Waters meant when he called this show a Trojan horse. The eleven o’clock number, “I Know Where I’ve Been,” is sung by Motormouth Maybelle. She moves us away from some of the sillier or more naive aspects of the musical and reminds us more poignantly of the struggle for equality. She reflects on how the black community has “lost so many along the way” and that “there’s a dream in the future/ there’s a struggle that we have yet to win.”

Hairspray—The Broadway Musical (2019): Ensemble. Photo by Jenny Graham, Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

The closing song, “You Can’t Stop The Beat,” literally shines with flashy late ’60s costumes from designer Susan Tsu. The stage is crowded, and our protagonists are beaming with victory. The Corny Collins show is integrated; Tracy has won Miss Hairspray; the Von Tussels are rejected; and everyone, regardless of who they are, is singing together.

Although in his director’s note Moore describes Hairspray as “a show that foregrounds inclusivity, that acknowledges and celebrates difference, that insists on acceptance and equality, that makes joy – the rarest of qualities in today’s world – the delicious air we breathe,” I found this sentiment to be a bit lacking in the actual production. It seemed to me that very few of the actors with disabilities had speaking roles. This choice in casting defeated the purpose of this modern “integration.” White, able-bodied actors were still centered by the time the curtain closed. It’s a step in the right direction, but it didn’t quite reach the level of equity that was expected or wanted.

Hairspray ultimately reminds us that equality is what we should be striving for and diversity is what we should be celebrating in an accessible way. This is why it is a story worth retelling and re-examining. In a time where we all get burned out by the news and by being active advocates and allies in our own lives, Hairspray remains a joyful rebuttal and rejuvenating form of resistance.

Hairspray is at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival until October 27, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Taylor L. Ciambra.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.