The civil war in Syria spawns image after image of hell on earth. Staging the stories of that conflict presents a challenge to playwrights: how do you write about horror in a way that is both accurate and entertaining? Goats, by Syrian playwright and documentary film-maker Liwaa Yazji, translated by Katharine Halls, is part of the Royal Court’s international project with writers from Syria and Lebanon and takes up this challenge. Her angle is to look at propaganda and to show how truth is the first casualty of war. She also examines what happens when that propaganda is questioned.

Set in a nameless village, one presumably loyal to the Assad regime, the story begins with a mass funeral of the young men who have signed up as soldiers. Lots of coffins, lots of families affected by the loss. While Abu al-Tayyib, the local party leader, leads the eulogies—stressing how the men died as martyrs for a just cause—one of the fathers, Abu Firas, the local school teacher, objects to the fact that the coffins are sealed and he hasn’t been able to see his young son. He won’t allow his unseen son to be buried.

From this initial conflict, the tensions of village society at a time of civil war are explored: the mothers struck dumb with grief, the young teenagers whose experience of war is confined to video games but will soon be called up or volunteer, the returning veterans of the conflict and the young opportunists. The ghastly injuries; the privations. But if the main clash is between a cynical state propaganda of martyrdom and terrorist enemies and the more questioning criticism of Abu Firas, a strong story struggles to emerge from the mass of detail.

What apparently has been happening is that the young village soldiers are captured by the enemy, who force them to phone home and tell their nearest and dearest that it is they who have captured the enemy, and then ask: what shall I do with these prisoners? Their captors then turn the suggestions of their relatives onto their prisoners—with gruesome results. As the death toll rises, Abu al-Tayyib has a good idea: he will present a goat to each family who has lost a son. It’s a practical form of compensation and welfare.

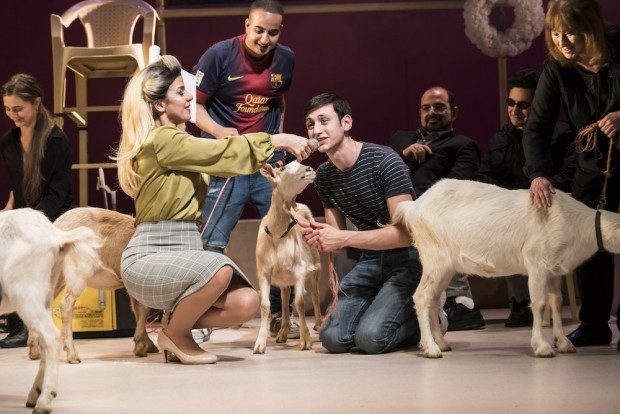

Enter the goats. And, boy, are they scene-stealers. The minute they arrive, they fascinate the audience. The goats are great. They are white, brown, golden, and dappled. They have been washed and groomed. They look brilliant. Their hair shines in the light. Glow-goats. At first, they look nervous, then they settle down. They twitch their ears. They scratch themselves. Then they relax into their roles. They say “Ba,” sit down and seem to fall asleep (or maybe they’re only acting). Then they start to misbehave (a bit). They eat the prop flowers, they lick the floor. They kiss. They jump up. At all times, they are photogenic and fascinating.

If Yazji’s play has a lot of problems—its storytelling is flabby, most of its dialogue is crude and documentary, and it is repetitive—the goats emerge as the real stars. When they are off-stage, the piece’s interest slackens and the rambling, baggy nature of the play is exposed. At its best, it has a couple of scenes of chilling ferocity, with the return of a “hero” the high point, and there is an Orwellian understanding of propaganda and lies, but for the most part, it is more documentary than drama. Even if the macabre absurdity of hoping to substitute goats for lost children is a strong indictment of government policy, Goats is slack, humorless, and boring.

While the play certainly has its head screwed on right—after all, it is hard to defend flagrant propaganda about martyrs and terrorists (which is also a tactic beloved of our own dear militaristic state)—there is not enough content here to make up for the weakness of the writing. I did like the cynical and manipulative Abu al-Tayyib’s conclusion that “people always choose the lies they know, the lies they were bought up on,” and his fast-thinking reinterpretations of the final tragedy are impressive, but most of the rest felt a bit too generalized and abstract.

And, despite the live goats, Hamish Pirie’s production doesn’t help. It is messy and unfocused. Designed by Rosie Elnile, the stage is a cluttered pile of coffins, fridges, and high seats, none of which look very pretty or evocative. The use of live video and microphones is distracting, and so the actors are upstaged by both technology and stage animals. Carlos Chahine (Abu Firas) and Amer Hlehel (Abu al-Tayyib) only occasionally generate some dramatic energy, and Amir El-Masry is powerfully convincing as the angry returning hero. The rest include Sirine Saba, Souad Faress, Ethan Kai and Isabella Nefar. But there’s something very wrong with a show where, at the end, the animals get more applause than the cast.

Goats is at the Royal Court until December 30.

This article originally appeared on Aleks Sierz on December 1, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.