The Festival Internationale Neue Dramatik (FIND) just closed in Shaubuhne Theater in Berlin. From March 30 to April 9, 16 productions from all over the world were seen, which in their own way deal with the Festival theme “Democracy and Tragedy.”

European and Western democracies find themselves in a severe process of radical change: national bankruptcies, an evergrowing influence of economic interests and lobbying on political decision-making, the increasing gulf between the rich and the poor, unemployment, terrorism, scarcity of resources and the reversion to nationalism and right-wing populism threaten social harmony, solidarity and open borders.

Against the backdrop of this gloomy panorama, the 2017 Festival of International New Drama was drawing together productions from internationally renowned theatre-makers under the collective title of “Democracy and Tragedy,” two concepts which have been closely linked since Ancient Greece. For Attic democracy was predicated upon the experience of tragedy as political consciousness and a delineation of existence. The depiction of all the emotions and culpable entanglements which were repressed in political reality was intended to purge the gathered public, via pity and fear, of those very emotions and entanglements.

Following these origins of the theatre, the works presented in FIND 2017 address the current state of democracy, its imperilment, repressed guilt and contradictions. They interrogate social and family inheritances and our concept of community, as well as the individual’s place within it and, use the stage to contemplate how we can live together in the future.

The festival opened with a play by the Spanish director and performer Angélica Liddell, who is working with a German ensemble for the first time, staging her play Dead Dog at the Dry Cleaner’s: the Strong. It is about Europe in a dystopian future: the government has called the “security” phase. All migrants are deported, any crime eliminated. “When I wrote the play ten years ago, the US marched into Iraq after the assassination attempt on the World Trade Center. But in the end it became a prophecy of what would become of Europe,” says Angélica Liddell.

Dry-cleaner Octavio fornicates with his customers’ washing and clings onto, in both senses of the word, his sister, the prostitute Getsemani. Taking refuge with them is museum guard Lazar who has quit his job because being responsible for the security of works of art causes him to have panic attacks. Lazar lusts after the teacher Hadewijch who lost her last job because she had sex with a 12-year-old boy. She comes to the dry cleaners searching for her lost dog Rameau – not realising he has been slain by Octavio in a fit of paranoia. The dead dog is nevertheless given striking voice in a colourful stream of abuse – he is played by an actor whose performance fee is cheaper than that of a real dog. Via the mysterious Combeferre, puppet-master of this painful experimental set-up, Liddell interweaves the plot with the writings of Rousseau and Diderot and, in doing so, creates the nightmare scenario of a degenerate society which, through the promise of absolute security, has lost its freedom: the borders are closed but the people still live in a constant state of fear and paranoia.

The Spanish writer, director and performer Angélica Liddell is one of the most prominent figures in the international theatre scene. With her texts, she eloquently rails against violence, chauvinism and vulgarity and, in doing so, always discovers the most yawning abysses and largest contradictions to be in herself. Dead Dog at Dry Cleaners: the Strong is the first text she is staging with a German ensemble.

March to November 2016. The kitchen in the Gabriel family home in South Street, Rhinebeck, a small town 100 miles north of New York. In these three plays, real-time snapshots allow us to follow not only the American presidential election but also a year in the life of a middle-class family and the private hopes and fears of its members. In his new trilogy The Gabriels: Election Year in the Life of one Family. Part I: Hungry, Richard Nelson interweaves big national events with small occurrences in private lives and presents us with a portrait of a world in which the personal, social, cultural and political are all inseparably connected. The three parts of The Gabriels premiered on the days in the election year on which they are set – when neither the writer, actors nor characters in the cycle knew the results of the votes.

Friday, 4 March 2016, 6pm–8pm. It is the Friday after Super Tuesday, the day when the primaries take place in many states. Thomas Gabriel, a relatively successful dramatist, passed away a few months ago. Now his next of kin, Thomas’ widow Mary, his ex-wife Karin, his brother George and wife Hannah, his sister Joyce and mother Patricia, have gathered to remember him at the family home. While they prepare ratatouille and apple crumble together, they talk: about their small town in which the newly- arrived wealthy are making life increasingly difficult for the long-established residents and about Hillary Clinton who is the same generation as them and who they regard with a mixture of scepticism and hope.

The Gabriels: Election Year in the Life of one Family. Part 1: Hungry by Richard Nelson

Direction: Richard Nelson (New York). Photo: Joan Marcus, 2017

From the perspective of today’s (post)democracy Romeo Castellucci (Cesena) identifies Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America from 1835 as the turning point in European thought about the state per se. Castellucci’s production associatively follows the story of this young Frenchman who contemplates American democracy with both wonder and fear.

Democracy in America by Romeo Castellucci (Cesena) freely inspired by the book by Alexis de Tocqueville. Photo: Luca Del Pia 2017

“This performance is not political. This performance is not so much a reflection on politics, as – if anything – on its end. In 1835, for the fi rst time, a European turns his eyes away from Athens. Alexis de Tocqueville witnesses the birth of the United States of America at the time when a new Democracy was being created from the seeds of the principles of Puritanism and a true equality among individuals. This implies the decline of Tragedy, understood politically as an awareness and comprehension of being. The great artificial laboratory of the negligence of being – tragedy – has thus been dismissed, forever. The vital and antibiotic experiment inherent in Athenian democracy has been relegated to the archive, along with the attempt – for the brief duration of a performance at the Theatre of Dionysus – to situate oneself beyond the limits of democracy itself, so as to listen, time and time again, to the dysfunction of existence, the lament of the expiatory victim, whom no politics is able – even today – to save. No more sacrifice, but still no politics. No more Gods, but still no city of man. The Scapegoat has been driven out, the knife has fallen out of our hands, and the sky is empty, new, blue and cold. All that remains is the empty ceremony that celebrates the grandeur of this loss.” – Romeo Castellucci

In Democracy in America, one of the fundamental texts underpinning the contemporary Western world’s political vision, Tocqueville described a new model of representative democracy, even while pointing out its dangers, such as the tyranny of the majority, a weakening of intellectual freedom when faced with populist rhetoric, and the ambiguous relation between collective interests and individual ambitions. Romeo Castellucci (born in Cesena in 1960) follows his example and positions himself at a time, which precedes politics.

Tristesses by Anne-Cécile Vandalem (Brussels/Liège) is set in a contemporary Europe where right-wing populists are gaining a growing influence, including Martha Heiger’s North European ‘Party of National Awakening.’ On the fictional Danish island of Tristesses, the body of Martha’s mother is discovered. She has hanged herself and is wrapped in a Danish flag. Martha attends her funeral. Party leader Martha Heiger, who is just about to be elected Prime Minister, has a strong interest in hushing up the affair. Her arrival is announced on the island for the funeral. Two young women whose future has been threatened by the politician plot to kill her. But on the day of the burial itself, the situation is turned on its head … In Tristesses, Anne-Cécile Vandalem, who herself plays Martha Heiger, explores the relationship between power and emotionalization. The tone of the production constantly fluctuates between criminal investigation and political comedy. With a large ensemble cast, live video and music especially composed for the piece, along with a rich vein of dark humour, Anne-Cécile Vandalem lays bare how contemporary politics is rendered hysterical, emotionalised and manipulated as well as revealing the questionable role the media plays in political discourse. Using black humour, Vandalem lays bare how contemporary politics is rendered hysterical.

Tristesses. Concept, Text and Direction: Anne-Cécile Vandalem (Brussels/Liège). Photo Phile Deprez, 2017

Hamnet by Irish theatre collective Dead Centre (Dublin/London) is devoted to Shakespeare’s only son who died at the age of eleven. Hamnet is too young to understand Shakespeare. We are too old to understand Hamnet. The boy’s father, the famous poet who had abandoned his family and was pursuing his theatre career far away from his family, was unable to get back to Stratford-upon-Avon in time to see his child one last time before he died.

In 1599 Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. A single letter separates Hamnet from the philosophical heights of Hamlet. Unlike the Prince, he cannot ask “to be or not to be.” Condemned not to be, he now seeks to understand the world from which he has been wrested. While waiting for a visit from his father – a visit that may never happen – all he has are the plays to act as a surrogate parent. But what is Shakespeare telling us? How to be? Or how not to be? Youth reaching forward to a life it will never know, an audience reaching back to a life it has forgotten. Two generations, asking each other what they want to pass on and receive. In 2016 the Irish theatre group Dead Centre featured in FIND for the first time with Chekhov’s First Play and LIPPY and were an exciting new discovery for Berlin. In their work, Moukarzel and Kidd combine Anglo-Saxon narrative theatre with continental European director’s theatre, play with theatrical conventions whilst also creating a commentary on their own work and on the possibility of art. A thinking space develops between two generations who ask themselves which legacies they wish respectively to pass on and receive.

Dead Centre has been founded 2012 in Dublin by Bush Moukarzel and Ben Kidd. They developed their first project Souvenir for the 2012 Dublin Fringe and it then appeared in London and New York. Their second project (S)quark! was performed in Dublin and then travelled to Russia (2013). LIPPY celebrated its premiere in Dublin ( 2013) and has already gone on to appear in New York, London, Germany and Edinburgh. In 2015, Chekhov’s First Play premiered in Dublin and it has played across the world, including Holland, Estonia, Berlin, Bordeaux and Brisbane.

The Colombian collective Mapa Teatro (Bogotá) is showing LOS INCONTADOS – Anatomía de la Violencia en Colombia: un triptico, a panorama of the wave of violence which has defined the country for over half a century. Part 1 turns an Afro-Colombian ritual into a delirious performance: masked men dressed as women trek through the streets whipping everyone who is not masked and a transvestite. Part 2 presents the ghost of a murdered drug mafia overlord who, in the company of his bride, must look the ghosts of his own past in the eye. In Part 3 a family wait in front of the radio for news of a revolution that will never come to pass.

Three microcosms located between fantasy and reality, three set designs nestling one behind another: combining extraordinary narrative and visual montage methods, in THE UNACCOUNTED, the Mapo Teatro transdisciplinary collective from Bogotá chart an “Anatomy of violence in Columbia,” which has defined the country for well over half a century and notably led to the bloody guerrilla war whose end has been under negotiation for many years. Each part depicts a single side in this long war and shows the narrow edge which separates celebration from an outbreak of violence. Together the three parts form a grand vision – constructed from cultish and surreal elements – of Latin American democracies since the end of the Second World War.

The Columbian Mapa Teatro collective has been one of the most renowned theatre companies in Latin America for over 30 years. Founded in 1984 in Paris by the siblings Rolf, Heidi and Elizabeth Abderhalden, it has been based in Bogotá since 1986. Mapo Teatro created an extremely individual universe dismantling and combining various genres and art forms in which myths, history and the present, private and public spaces, opera, theatre, cabaret, radio and video all flow into one another.

LOS INCONTADOS – Anatomía de la violencia en Colombia: un tríptico by Mapa Teatro (Bogotá). Concept, Dramaturgy and Direction: Heidi and Rolf Abderhalden. Photo: Filipe Camacho, 2017

In Verein zur Aufhebung des Notwendigen Christophe Meierhans (Brussels) throws a dinner party about democracy. Following recipes from a cookery book written by Meierhans, the audience prepares a two-course menu complete with appetisers and drinks. The kitchen becomes a theatre of generally binding decisions made collectively or individually. The food will taste exactly like the sum of these decisions – an experiment with an open ending.

A dinner party brings people together; it should be jovial, comfortable and sociable. However, food is always a topic that is loaded with very intimate beliefs: existential, ethical, aesthetic, economic, social, ritual or religious. In other words, a dinner party offers the perfect setting for a political showdown. For the duration of the performance, the audience becomes a community, the Verein zur Aufhebung des Notwendigen in which each individual brings their personal preferences, values and convictions to a collective decision-making and creative process. Following a recipe book created by Christophe Meierhans, the spectators jointly prepare a two-course meal, including an appetiser and drinks. They set the table as well as the tone of the evening and eat together. The kitchen becomes the stage for collectively or individually made binding decisions. Each spectator carries the responsibility for making the evening a success but this is not about reaching a consensus: objections, arguments and refutations are all permitted. The finished meal will taste of the sum of all the decisions made by the audience – an open-ended experiment.!

Acceso is the first theatrical work by multi-award-winning Chilean film director (Neruda, Jackie, El Club) Pablo Larraín (Santiago de Chile). Actor Roberto Farías plays Sandokan, an outsider who flogs cheap goods to passengers on the Transantiago bus. Bit by bit, he tells stories from his past which was shaped by poverty, violence and sexual abuse and creates a savage indictment against a deeply corrupt system. Sandokan is someone with nothing left to lose. He volubly flogs cheap tat to people on the Transantiago bus in the hope of finally gaining “acceso” – entry into a better position in society. Whilst he bluntly advertises his hair and footcare articles, his tatty advice booklets, children’s bibles and even the country’s constitution, he forces his stories upon the people and tells them bit by bit about his past shaped by poverty, drugs and violence. We learn that he was abused as a child by priests and other »uncles« who hailed from a better class of society. He bellows out all the brutal, monstrous details, pillories the state authorities who sedate children with psychotropic drugs and send them back to the disastrous circumstances from which they have sought to escape. He attacks the homes whose gruesome practices are even worse than these young people’s everyday lives of abuse and exploitation. Ultimately, he even craves a return to the so-called “love” of which the priests gave him a taste. Working with actor Roberto Farías, who already played the pariah Sandokan in Larraín’s award-winning film El Club, the director has developed a ruthlessly candid monologue. Whereas the film centres around the perpetrators, this play focusses on the victims of sexual abuse and delivers an unflinching indictment of a deeply corrupt system.

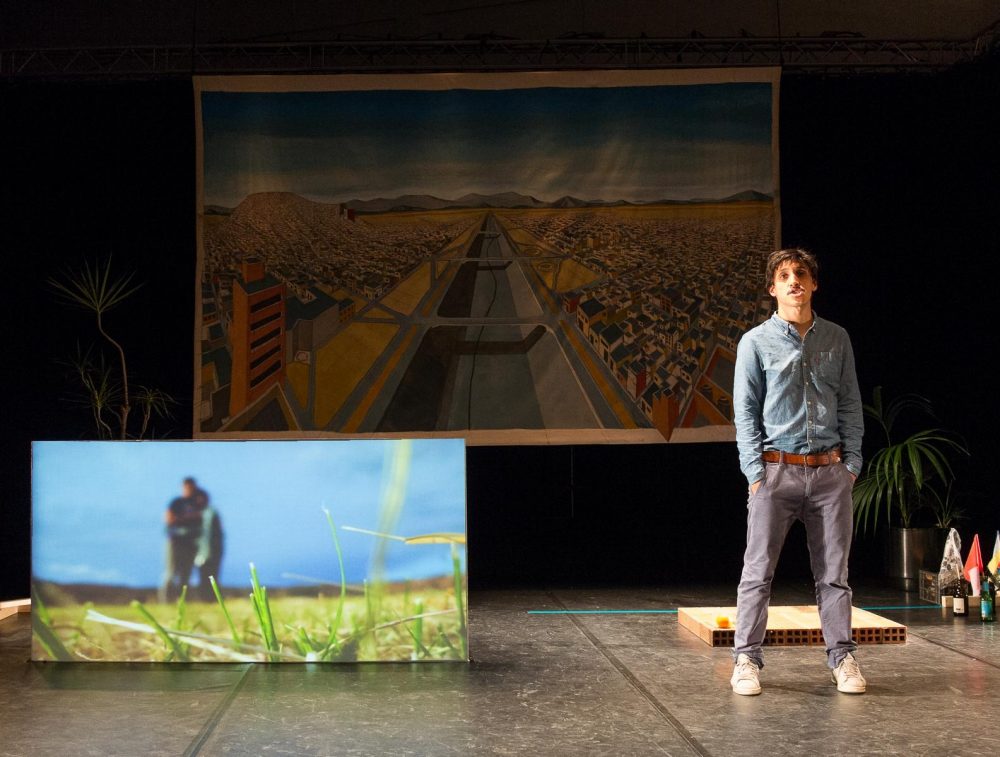

Tijuana by young Mexican theatre collective Lagartijas tiradas al sol (Mexico City) is part of a triptych entitled Democracy in Mexico and it is the result of a real self-experiment made by Gabino Rodríguez, founder and artistic director of the Lagartijastiradas al sol theatre collective, together with Luisa Pardo. The show is based on an actual personal experiment: for six months writer and performer Gabino Rodríguez worked for minimum wage under an assumed identity on a factory assembly line in the border city of Tijuana. Whilst there he was not only confronted with inhuman methods of exploitation and vigilantism amongst the workers as a result of a failing system of law and order but also with his own contradictions and social prejudices as a middle-class artist.

Inspired by the methods of Günter Wallraff and Andrés Solano, for six months Rodríguez abandoned his life in Mexico City as a writer, director and sought-after theatre and film actor to work on an assembly line in a Tijuana factory on the US border. He passed under the false identity of ‘Santiago Ramírez,’ wore a fake moustache, had no contact with friends, family or colleagues and earned the legal minimum wage which, according to the Mexican constitution, “should cover the normal material, cultural and social needs of the head of a family and facilitate the compulsory education of his children.” That, at least, is the claim made by the legislators. In reality, it means: 73 pesos per day, which is less than 3.50 Euro, a sum almost impossible to scrape by on for a single, malnourished sleepwalker like ‘Santiago Ramírez.’ It is a role which Rodríguez, as a talented actor, initially slips into without raising any suspicions and for which, like several million Maquiladora workers, the merciless exploitation of his physical strength and vitality is the price exacted for free trade and company profits in the Mexican border region. Soon, however, he becomes plagued by ethical considerations for his co-workers and the family of his landlord, all of whom trust the worker ‘Santiago Ramírez’ although they are actually being used by a middle-class artist as research subjects for his theatre play.

Tijuana is the prelude to a large-scale political and social panorama entitled Democracy in Mexico (1965–2015) which is designed to be told in 32 parts – one for every Mexican state. It is the latest project of the Lagartijas tiradas al sol collective which, since being founded in 2003, has explored the borders between documentary and fiction in various theatrical forms to reveal the contradictions in Mexico, thus aiming to use the theatre as a means of political mobilisation. To date, four parts of this project have been realised. Lagartijas were most recently at FIND in 2014 with a documentary project about the PRI State party: Isle Melt the Snow of a Volcano with a Match.

Tijuana by Mexican theatre collective Lagartijas tiradas al sol (Mexico City). Photo:: Escenas de cambios, 2017

Pendiente de voto lets the audience decide on questions of the commonwealth in an electoral experiment. Equipped with voting devices, the spectators become a model society. Individually, in pairs or in groups, they must defend their positions, convince others and make decisions. With Pendiente de voto, Catalan director and performance artist Roger Bernat is embarking upon an experiment: the Globe Theatre space at the Schaubühne will become a parliament for the duration and the audience will create the model of a community which takes its fate into its own hands. Equipped with an electronic voting system, a computer – ‘the system’ – will take spectators through a three-phase decision- making process. They must express their points of view, devise solutions together and vote on them in a very direct and transparent way. They are expected to take a position on questions of social interaction and personal preferences as well as on national security, health, gender politics, justice, freedom of religion and immigration. The everyday is juxtaposed with the emotionally charged, absurdities with the highly political and socially relevant. Initially, the spectators will vote entirely individually, then in pairs and finally in the form of party factions. The exercise will constantly demand group discussions as people have to convince others of their own views and bring about decisions by votes that will determine the future. More and more, however, the system will begin to manipulate the initially transparent and direct path of democracy and influence things in its own favour …”In ›Pendiente de voto‹ I am testing parliament as a form of theatre” – explains Roger Bernat. – “To me, it’s not about reconstructing a fictional parliamentary debate; instead, my goal is a politics of fiction. Just as politicians today play at theatre, I want to make politics in the theatre together with the audience.”

Iphigenia in Splott by Gary Owen (Cardiff) tells the story of an impossible love between a young Welsh working class woman called Effie and a disabled ex-soldier. Splott, a working-class district of Cardiff in Wales. Effie is young, unemployed and furious at the world. The only brief respite from this miserable existence is to get drunk and high. Every night is taken up with boozing, arguing, fucking and sometimes even fighting; every morning begins with a hangover and a beer to ease the headache. Then, next evening, it starts all over again. But one night Effie meets ex-soldier Lee who had part of his leg blown off in action. Effie and Lee are immediately attracted to one another and, for the first time since the explosion, Lee reveals his body to a woman. Effie knows how important this moment is for Lee and takes the responsibility very seriously; their vodka soaked night together is unforgettable. Next morning Effie feels something totally new and wonderful: she is no longer alone. Effie and Lee swap phone numbers and arrange to meet the same evening. But Lee fails to turn up and, when Effie tries to phone him, his number doesn’t work. »Iphigenia in Splott« is inspired by the story of Iphigenia who, in Greek mythology, was sacrificed by her father to gain good winds for the voyage to Troy. But this play tells a contemporary tale against the backdrop of a crumbling welfare state and asks the question: who today is being sacrificed for motives of profit and self-interest?

Gary Owen, is the winner of the Best New Play at the UK Theatre Awards 2015 and the James Tait Black Drama Prize for Iphigenia in Splott, as well as the George Devine, Meyer Whitworth, and PearsonBest Play Awards. His other plays include Violence and Son, Crazy Gary’s Mobile Disco, The Shadow of a Boy, The Drowned World, Mrs Reynolds and the Ruffian, and Love Steals Us From Loneliness.

Sei, wer du nicht bist (Be the one who you’re not) by Saman Arastou (Tehran) talks about the situation of transgender people in Iran, drawing on the personal experiences of the author, director and leading actor of the play. Director, writer and actor Saman Arastou addresses the situation of transsexuals in Iran. Using his own biography as a starting point he deploys the simplest of theatrical techniques to make intensely tangible the violence which society visits upon people who feel they are of a different gender to the one they were born with. Saman Arastou was born a woman but decided in 2008 to undergo a sex change operation, something which is actually legal in Iran. Since a fatwa by the country’s founder Ayatollah Khomeini, transsexuality has been considered a curable disease. Whoever feels trapped in the wrong body may have an operation. But, although the surgical intervention may be compatible with contemporary Islam in Iran, every day life for transsexuals in this strongly Shiite theocracy is characterised by stigmatisation and intolerance. And homosexuality is still punishable in Iran. For many homo sexuals, the operation is the only way to escape this punishment. In Be the one who you’re not, the power of the theocracy even makes itself felt in the protecting atmosphere of the family: Arastou is pushed back into the role of a woman by his siblings and brutally forced into a wedding dress to marry a man. A silent, powerful evening about a person who does not want to be forced to be either a man or a woman.

In Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, US playwright Kevin Armento tells the story of a schoolboy having an affair with his maths teacher – from the perspective of his mobile phone. Christoph Buchegger will present the play for the first time in Germany in a workshop production with members of the ensemble of the Schaubühne. Red McCray is a typical high school student in a Californian nowheresville. Lone wolf, class clown and child of divorced parents with only a single friend: his mobile phone. When one day this is confiscated in a maths lesson, a more intimate bond suddenly develops between Red and his teacher. After inadvertently pocketing the phone, she trawls through his photo album and, once she has returned it, begins to send him messages. With each photo and text, she causes the teenager’s facade to crumble a little more, initiating a relationship which poses an unsolvable equation for the two. The narrator and witness of this doomed affair is Red’s mobile which allows us to share in the personal texts as well as the fluctuating emotions of the characters and the tragedy that is inexorably unfolding. At a rapid pace, American writer Kevin Armento tells of the illusory nature of electronic connections and the dangers of isolation in the time of digital love.

In From here I will build everything the Belgian actor CédricEeckhout, who at FIND 16 acted in Sanja Mitrović’s production Do You Still Love Me?, conflates his personal crisis with the European crisis in a short stand-up monologue: “My mother is Wallonian and my father is Flemish. They divorced in 1982. Ich bin en Europäisch produit. And I am in crisis. Just like Europe.” Actor Cédric Eeckhout detects in his first self-created performance with his mother and his tomcat Jesus political and private crisis scenarios between his own life and developments in the European Community – beginning with the shared initials CE, Cédric Eeckhout and Communauté Européenne, and ending with painful separations in his personal life and, sandwiched between debt crises and Brexit, the gradually disintegrating EU. He embarks on the search for a relationship which will last.

The festival also included various post-show talks, a panel discussion on ‘Democracy and Tragedy‘ as well an edition of our political debate series Streitraum on the subject of “The Limits of Respect – the Radicalised Society.”

For the seventh time now, the festival was accompanied by FIND plus, the workshop programme for international theatre students, supported by the Allianz Kulturstiftung and the Deutsch-Französische Jugendwerk (DFJW).

Reposted from press releases of https://www.schaubuehne.de

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by The Theatre Times.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.