Given the year’s unsettling mixed-bag of a global pandemic, racial reckoning, political strife, and various man-made and natural crises (murder hornets, anyone?), the chaos of 2020 has become both a running joke and a deeper object lesson in navigating uncertainty. Moreover, as we address our individual and collective roles in the seemingly-random events before us, many have found ourselves pondering age-old questions of fate and free will, and the extent to which either governs our lives. This is Not A Theatre Company’s Readymade Cabaret 2.0, an online iteration of its 2015 piece on chance, randomness, and creativity, playfully greets these queries, its new digital components adding further depth and humor to the concepts it depicts.

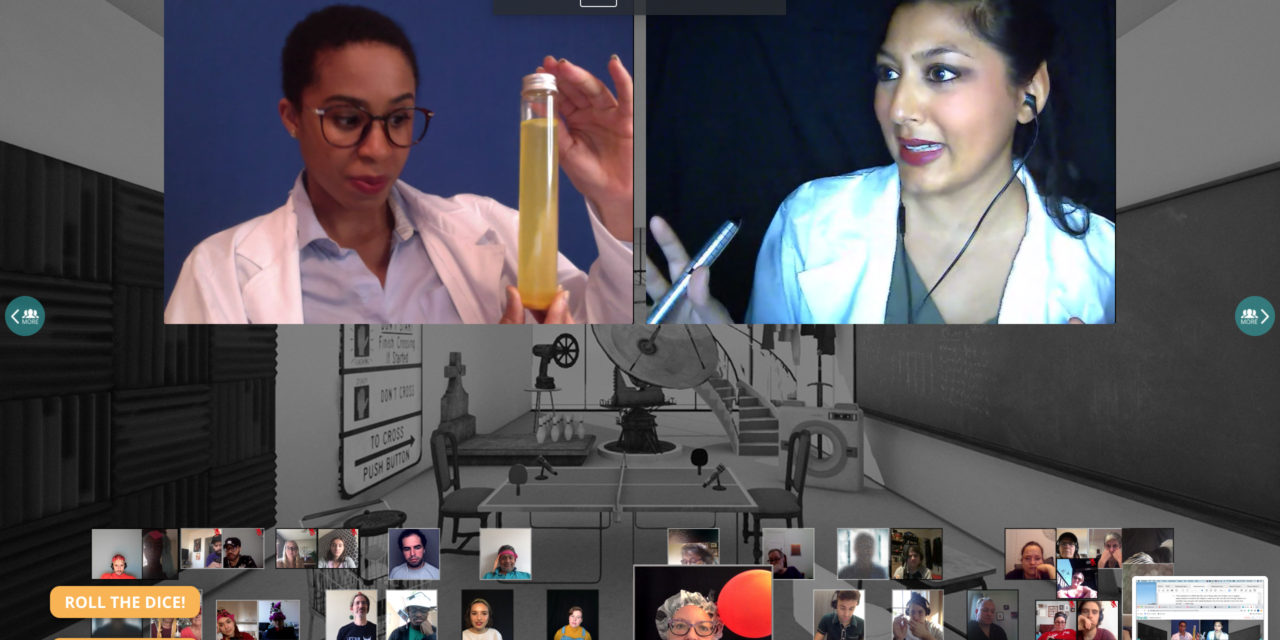

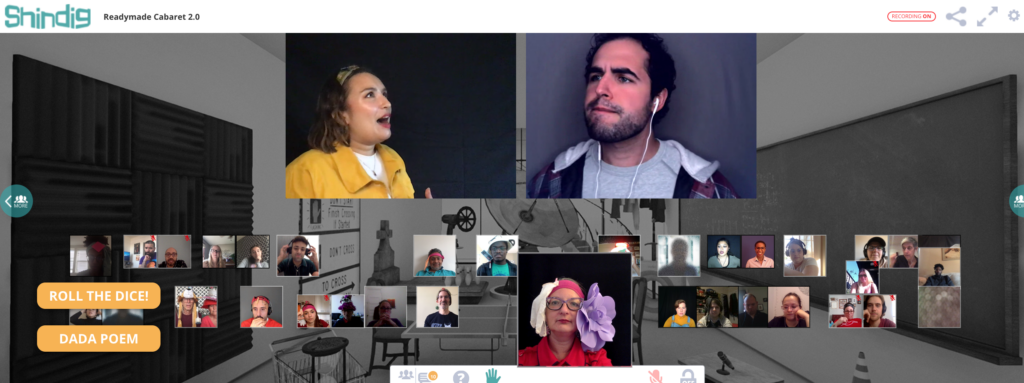

Readymade 2.0 takes place via Shindig, an interactive event platform. More evocative of a lively real-world conference than a video call, Shindig’s setup lends itself to the participatory elements on which the piece relies. The site’s “podium” function lets the host spotlight performers or bring audience participants onscreen, and attendees may enter one-on-one video chats or hop into six-person breakout rooms to watch the performance as a group. Viewers may also converse through a type-in chat, click buttons to generate found-text poems, or roll virtual dice to determine scene order and layout. As audience members may be more accustomed to such hosting sites Zoom or Google Hangouts, Shindig’s shifting video squares, piped-in pre-show chatter, and various interactive features can initially overwhelm those new to the platform, but the ensuing settling-in, and director Erin Mee’s guidance, reveals this format to be more user-friendly than expected.

Sporting an array of clever hats, Mee familiarizes us with the show’s conceptual framework: after the First World War and its resulting social chaos, percolating fascism, and economic upheaval (sound familiar?), the artistic movement known as Dadaism posed an outright rejection of conventional logic and structure. As such, Dadaist art favors chance and subjectivity in both its creative process and interpretative style, often actively spoofing the norms of its predecessors. In this vein, Readymade 2.0 takes randomness as its guiding principle: audience volunteers roll virtual dice to determine the order in which any of the show’s 28 scripted scenes or interactive sequences appear within its 50-to-75-minute run time.

Marisa LaRuffa (L) as Amy and Christopher Morriss (R) as Peter.

Performed by TiNATC’s ensemble (Kara Green, Marisa LaRuffa, Beatrice Antonie Martino, Jonathan Matthews, Chris Morriss, and Lipica Shah), Readymade’s scenes vary at any given performance, ruling out much chance of a linear narrative, but many of the same characters and themes emerge throughout. A couple’s first-date discussions of lab rats and iTunes’ shuffle feature lead to musings on fairness, memory, and regret as the pair considers whether to nurture or abandon the relationship. A medical researcher spars with her colleague over drinking an experimental substance, while the aforementioned lab rats face similar distress over whether their chemically-laced “yum drinks” may be poisoning them. In one scene, a scholar posits whether the Ancient Greeks were happier for their staunch belief in Fate; in another, an omniscient judge metes out punishment or salvation for a young woman based on her acceptance of this doctrine. Shorter sequences discussing whether an absent “Hannah’s” illness is or isn’t her fault, strike chords against the current health crisis and the spectrum of individual responsibility in preventing or spreading disease.

Dancer-performers Jonathan Matthews and Beatrice Antonie Martino supplement the action with live and pre-recorded music and movement. Straddling experimental film and dance video, the recordings blend multiple dance clips within one backdrop, or combine Martino’s compositions with overlays of natural phenomena. For the live versions, Mee instructs us to direct “chance dances” by typing body parts, adjectives, numbers, and mechanical actions into Shindig’s chat box; onscreen, the hyper-expressive Matthews and Martino turn these orders into short-form choreographies of quizzical eyebrow bounces, ominous elbow rotations, and joyous butt-wiggles. Using a technique known as aleatory composition, Matthews also creates music from our prompts, making gleeful cacophony with bells, cheese graters, kitchen timers, and other household items. It’s terrific fun to co-direct these elements, see the performers respond in real-time, and revel in the absurdity we create. The experience recalls countless quarantine DIY projects–which, however wonderful or terrible the results, still make for interesting at-home entertainment.

Surprisingly fit to present circumstances, Readymade 2.0 speaks to our endless search for meaning, and to the folly of taking this search, or ourselves, too seriously. Even as the events of 2020 have spawned untold ingenuity, resilience, and collective action, they have also humbled us, revealing the limits of our strongest wills and best-laid plans. As such, Readymade 2.0 affirms the power of chaos as a creative force, our embrace of it breeding meaningful tension, deep insight, and–in true TiNATC and Dada fashion–quite a bit of fun.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emily Cordes.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.