In Han Tae-sook’s Electra (LG Arts Center, April 26–May 5, 2018), the mourning daughter doesn’t sit around waiting for her brother to take revenge. Wearing short hair, combat boots, and a pistol at her hip, this Electra (Jang Young-nam) leads a rebel army against the usurper Aigistheus (Park Wan-gyu). She holds her mother Clytemnestra (Seo Yi-sook) prisoner in an underground bunker while her soldiers prepare extreme measures—a biochemical bomb strapped to a suicide vest—to win the war at any cost. Like Sophocles’ drama, however, revenge and justice run along parallel tracks, never to converge.

Han’s latest project resembles her most famous work, Lady Macbeth (1998)—another revision of a classical Western tragedy that focuses on the female characters. Han’s performance text for Lady Macbeth is a fragmented, postmodernist take on Shakespeare’s play, meant to accommodate her use of object performance and traditional Korean music. Electra, on the other hand, is adapted by acclaimed playwright Ko Yeon-ok and largely follows the original play’s structure. As such, Ko and Han’s changes to plot, character and setting feel impactful, inviting comparisons to Sophocles’ version of the ancient story.

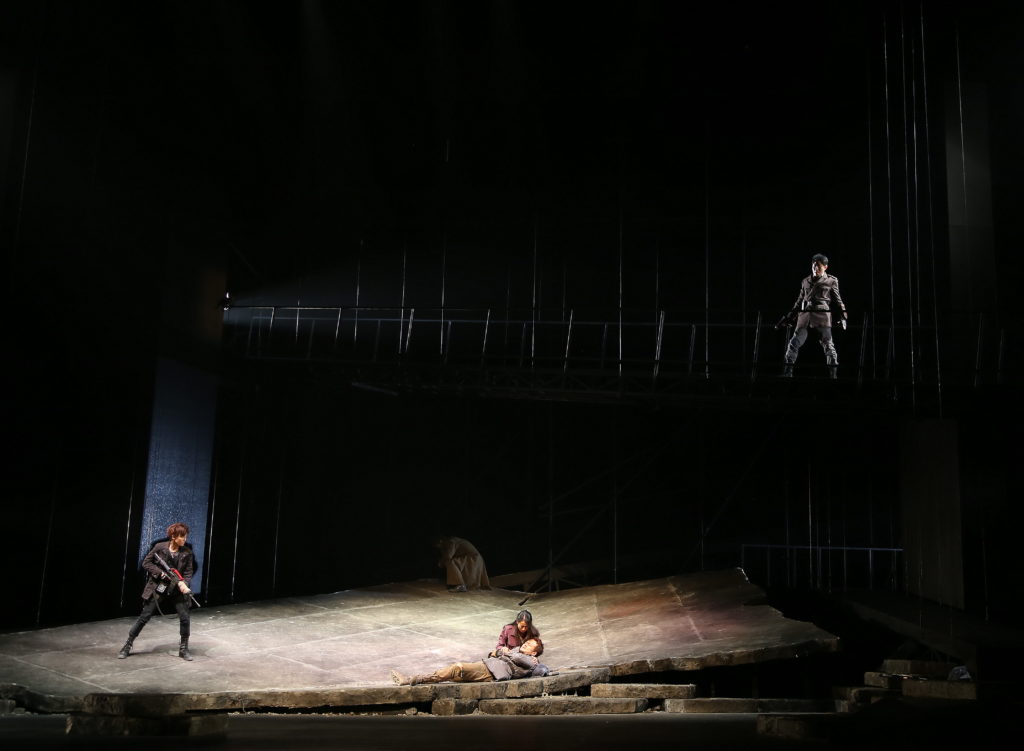

This Electra takes place in a fictional modern country during a civil war. The stage depicts the steel and concrete ruins of a massive temple dedicated to Agamemnon. Electra’s guerilla fighters—the Liberators, as they call themselves—razed the glorified tomb to denounce Aigistheus and Clytemnestra’s murder of the former king. Electra’s sister Chrysothemis (Park Su-jin) joins the rebellion, although she defends their mother’s unfaithfulness, reminding Electra that Clytemnestra isn’t defined solely by her maternal role. Later, we learn that Chrysothemis was sexually abused by Aigistheus after he seized power. She wants to destroy Aigistheus—she insists on calling him “Master” instead of “Father”—as much as she wants to protect Clytemnestra.

By launching the coup well before Orestes enters the scene, this adaptation disrupts the passive femininity ingrained in Sophocles’ classical drama. We learn early on that Electra married a fellow resistance fighter sometime after the uprising. (An interesting choice by Ko, since one interpretation of her name’s etymology is “unmarried.”) When Clytemnestra deridingly asks about their relationship, Electra replies curtly that they are first and foremost comrades. To Electra, marriage isn’t a way for a woman to secure protection in a hostile environment, which, of course, was one of Clytemnestra’s excuses. Later, when Electra and Orestes (Baek Sung-chul) meet, she surprises him with a gut-punch that knocks him to his knees. Even though the soldiers hail Orestes as a hero who will bring them victory, Electra makes sure that everyone knows who is in charge. At times, it seems as if Electra is consciously performing masculinity in order to lead the rebellion for her agenda.

Yet the adaptation fails to explain why the Liberators need Orestes in the first place. The long-awaited hero turns out to be rather unheroic; he hesitates when Electra asks him to fight, not because he has qualms about matricide but because he doesn’t like being used for someone else’s cause. The soldiers constantly chant “Orestes! Orestes!” in his presence, but he feels detached from his princely name, having lived peacefully under an alias for years. When he finally decides to join his sisters, he simply melts into the chorus of soldiers with no impact on the course of the plot. Meanwhile, Electra can train a gun at Clytemnestra’s head without blinking. She has the willpower to violate moral codes and curse the gods, though her thirst for revenge overwhelms her judgment. Chrysothemis also plays a key role, using herself as bait to spring a trap on Aigistheus, leading to his capture.

In addition to giving more agency to the women in the play, the adaptation also reflects on how violence is politically justified. The chorus of soldiers look to Electra for reassurance—that there is purpose in the destruction and blasphemy they commit. The young woman wearing the suicide vest (Min Kyung-eun) repeatedly voices her resolve, as if trying to drown out the doubts echoing in her mind. Also, not all of them are loyalists of the deposed king; some seem to believe that their new order will be vastly different from the previous monarchies.

Electra, directed by Han Tae-sook. Photo courtesy of LG Arts Center.

Unfortunately, Electra is too bent on personal revenge to provide the moral or ideological guidance that this insurrection needs. And so, the movement falls apart. The royal children torture Aigistheus after capturing him, reveling in his pain rather than granting him a dignified trial and execution. There are no grand ideals in this war, only petty vendettas. Perhaps realizing this earlier than the others, the Commander, Electra’s right-hand man, reveals that he is Aigistheus’ spy before unceremoniously gunning Orestes down.

What finally ends the cycle of vengeance isn’t heroism or divine intervention, but rather an unnamed foreign power taking advantage of domestic strife. In an unexpected nod to Euripides, invisible snipers in the wings assassinate the Commander, Aigistheus, and Chrysothemis. None of the characters understand what is happening as they die. Electra frantically yells, “Agamemnon is my father!” as bodies collapse around her. Instead of running, however, Electra drags Clytemnestra out of her cell to force out a confession before they too are killed. Even as her family and country fall, Electra can’t see beyond her rage.

Electra, directed by Han Tae-sook. Photo courtesy of LG Arts Center.

At the end of the play, soldiers in gas masks enter the stage, poking the dead bodies after some kind of gas weapon was discharged. This final image evokes the bleak ending of Hamlet, where struggles over filial obligation, morality, and legitimate rule end up meaning nothing in the face of hard power. But this ending is familiar in other ways as well. Han writes: “The excuses made by superpowers, pitting rebels against the government in failing states and profiting from the suffering of others, perpetuates tragedy in human history. Koreans have suffered in this way as well.” If the ancient Greeks felt powerless before the gods, the modern subjects of this play are powerless before Imperialism.

Electra is undoubtedly a flawed hero in this tragedy. But rather than covet the audience’s sympathy despite her shortcomings, Han and Ko contextualize Electra’s fixation on revenge, setting her as the leader of a coup in a weak nation too mired in internal politics to notice invaders on the border. Even though she ends up destroying herself, this Electra deserves having her name in the play’s title more than her classical counterpart.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.