There is no shortage of plays on the subject of mid-life crisis, from Alan Charles’ Midlife Crisis to Tracy Letts’ Linda Vista. Writer-director Pablo Remón has added to the mix with his tale of forty-something Toni (Remón regular Francesco Carril) and Olivia (Natalia Hernández) who are finding parenting two small children while keeping their dreams alive not so easy. Toni is a one-time writer now teaching at a private university, Olivia is a journalist. Their boisterous children, Amaya and Adrián, are humorously played by Marina Sales and Raúl Prieto interchangeably. Adrián has a Spiderman cape and matching eyewear while Amaya sports butterfly wings. There is a fair bit of bickering and chaos in the morning as the children are readied for school. Toni is trying to work out how he lost control of his life, confiding in his brother and his psychologist (both played by Prieto) while losing a grip on his domestic life and work.

With references to Hegel, Derrida — who is playing on the house television in an early scene — and other giants of political theory and deconstruction, this is a piece that is overtly literary in its game play, asking a series of questions about the ways in which fiction is created and how the self is constituted. It plays with time across a prologue and four episodes as the action weaves in past and reported action. Toni’s frustration as a writer with one published collection of stories and a novel that he is never completed is in many ways the pulse of the play; it contaminates his relationship with his brother and traps Toni in a past where, despite his best intentions, he finds himself turning into a version of his father that he doesn’t like. The play’s title comes from the fact that both Toni and Olivia have lost their enthusiasm for each other and for life – an enthusiasm that their rowdy children are full of.

Monica Boromello designs a plywood box of sorts for the action with platforms for wheeling props on and off stage from the wings. As the action progresses and Toni’s existentialist crisis spirals out of control, the family’s living room becomes ever more cluttered: a metaphor of sorts for Toni’s overactive mind. Bauhaus and David Bowie posters point to the couple’s artistic tastes. Ana López Cobos’s costumes are a mixture of warm ochre and forest green – the soothing colours only work on a skin-deep level, however, with seething emotions threatening to rise from above the surface and rupture the artfully designed home.

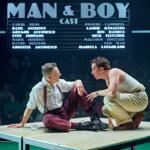

Marina Salas recounts her first crush as the teenage boy (Raúl Prieto) plays tennis in the distance. Photo: Geraldine Leloutre

The play’s wonderful prologue has Salas as a fourteen-year-old with a crush on the new boy in town (Prieto) whose tennis moves are expertly choreographed as a repetitive dance while Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream” plays in the distance. It’s the town’s summer celebrations and young love blossoms – only the enthusiasms of first love are shown to be all too brief as the prologue is followed by Toni and Olivia’s routine-led existence with stressful mornings trying to get the children to school and more antics in the car as Toni navigates the rowdy siblings and inner-city rush hour traffic.

At one point, on leaving her unwell husband in hospital. Olivia’s mother (played by Sales) comments to her daughter that “I needed to escape from my life”. Only Toni doesn’t find it so easy to run away from his. He is seeking help from his psychologist and his brother but neither are helping him make progress; his sometime lover (played by Salas) can’t provide fulfilment. When he reflects on marriage that “it’s about marrying into a lineage”, there’s a sense that he can’t quite find the means to escape from his life because he isn’t sure he wants to. In many ways the play is a reflection on how far any of us are authors of our own lives.

Remón directs the action at a brisk and breezy pace. His writing is engaging and lithe. And while I found my attention wavering in the play’s final third, there is no doubt this is a play that spoke to the packed young audience at Madrid’s Teatro María Guerrero, who responded with laughter and loud applause. The cast are uniformly excellent; Salas and Prieto move effortlessly across a range of characters. Carril — a regular in Jonás Trueba’s wry comedies, including most recently Volveréis/The Other Way Around (2024) and Tenéis que venir la verla/You Have To Come and See It (2022) — has real chemistry with Hernández; the banter has something of the lively chemistry of Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby (1938) with elements of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. Men here are navigating a world where they may not want to be questioned and where life doesn’t quite deliver on what it promised.

El entusiasmo captures something of the zeitgeist of the times: as white males try and make sense of a world that may not have delivered quite what they expected. Realised with droll humour, it’s an entertaining, reflective piece that confirms Remón’s reputation as a writer-director exploring the faultlines of masculinity in crisis and the effects of this unravelling on the wider domestic environment.

El entusiasmo (The Enthusiasm) was presented by the Centro Dramático Nacional in association with Teatro Kamikaze and plays at the Teatro María Guerrero from 7 November to 28 December.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.