While working on her MFA in Writing from the University of San Francisco, playwright Marisela Treviño Orta became the Resident Poet for El Teatro Jornalero! in 2003. During this time, Orta witnessed firsthand the power of the theatre community and subsequently began to write plays. Since then, Orta’s playwriting career has skyrocketed. Notably, her play The River Bride won the 2013 National Latino Playwriting Award and received its world premiere production at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2016. Her other plays include Braided Sorrow, Heart Shaped Nebula, American Triage, and Wolf at the Door.

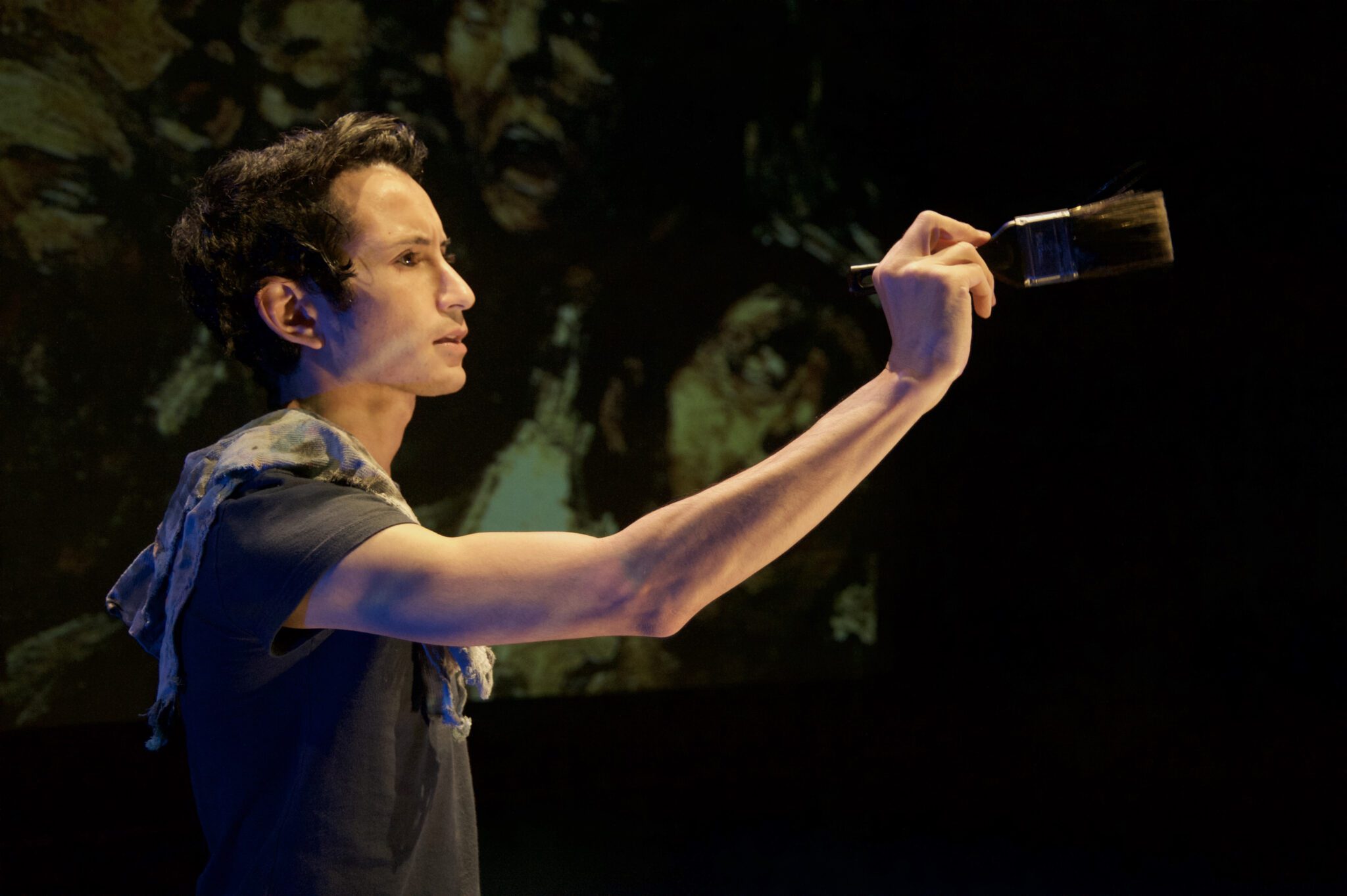

Orta’s latest play, Ghost Limb, headlines Summer of Xicanas: Theater, Film, y Encuentros at Brava! for Women in the Arts. Ghost Limb is part of Brava’s efforts to amplify the voices of professional Latina artists in the Bay Area and beyond. While originally from Lockhart, Texas, Orta found her voice as a playwright and theatre artist in the Bay Area, making this a homecoming of sorts.

In this interview, Orta discusses Ghost Limb, her grim Latino fairy tale cycle, and her time at the Iowa Playwrights Workshop, where she is currently pursuing her MFA in Playwriting.

Trevor Boffone: Your latest play, Ghost Limb, is set during Argentina’s Dirty War (1974-83) and also finds inspiration from the Greek myth of Persephone and Demeter. While Ghost Limb plays with metaphors and visuals to respond to Argentina’s violent recent past, in many ways the play is impressionistic through its use of the Persephone/Demeter myth. Can you tell us more about this?

Marisela Treviño Orta: Ghost Limb is the second play I ever started writing. It’s been on the shelf for about 10 years because I felt I needed more time to develop as a playwright before tackling it.

I was a poet for many years before transitioning to playwriting and I see my poetics heavily influencing Ghost Limb. As a poet, I’m an Imagist—driven by and focusing on visuals. In Ghost Limb the imagery is key to the narrative—there’s even one scene that’s completely without dialogue—just the visuals of the actors on stage and sound. The Greek myth of Persephone and Demeter knits the play’s imagery together—the goddess plunging the world into permanent winter when her child is stolen from her so that we see the emotional world of the play impacting the physical world on stage. The metaphor drives home the unnatural state the world is in—emotionally for the characters and politically as their country is being run by a military dictatorship.

Trevor: You’ve been working on Ghost Limb since 2007. Can you tell us more about the development process for the play?

Marisela: The first draft was finished sometime in 2008, but as I mentioned earlier I put that play on the back burner for a variety of reasons—I had two commissions to write and after writing them felt I needed more time to grow as a playwright before I could effectively work on Ghost Limb.

I didn’t do a rewrite of the play until 2015 when I presented it in a workshop at Iowa. I used the feedback from my playwriting peers and the dramaturgs in the program to fuel the next round of rewrites. By that time, I was in talks with Brava Theater in San Francisco about producing the world premiere so I used the resources at the Iowa Playwrights Workshop to prep the play for production.

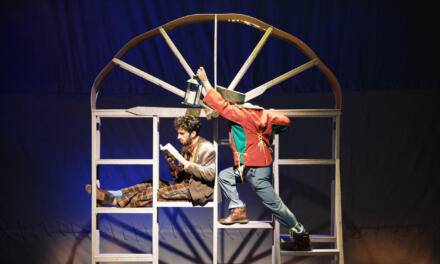

In the spring of 2016, I submitted a gallery production application for Ghost Limb and the play was accepted as part of the Iowa gallery season. Gallery shows get a nominal budget, but we have access to a wealth of resources—props, costumes, designers in the program, and actors. Faculty member John Cameron directed the play and I worked with John on rewrites before our rehearsal process began. As I had to be both playwright and producer, I knew there wouldn’t be much time for rewrites during the rehearsal process.

I used my gallery production as a sort of test kitchen to develop a new draft of the play and try out all sorts of staging choices. I really wanted to see what John and our designers would come up with and I learned a lot about the play through their choices. Doing so allowed me to enter my world premiere process at Brava with more informed ideas and recommendations.

After my gallery production at Iowa, I did two more rounds of rewrites as I worked with Mary Gúzman—the director helming the world premiere. While at times it was challenging to juggle rewrites with my responsibilities as a graduate student, I finished my rehearsal draft of Ghost Limb mid-May and we went into rehearsal June 6th.

Naturally, I’m making small adjustments and edits during our rehearsal process, but no big rewrites. We wanted the actors to come to the first rehearsal off-book to hit the ground running. And we’re running. We’re about to begin the last week of rehearsal before tech!

Trevor: Ghost Limb headlines Brava’s Summer of Xicanas, which, aside from celebrating the work of Xicana artists in the Bay Area, also examines our collective responsibility to the world we live in. What do you see as Ghost Limb’s role in this celebration?

Marisela: I studied Latin American history as an undergrad so I often have to remind myself that not everyone has heard of the Dirty War. Some of the feedback for my presentation at the workshop in Iowa was incredulous in the sense that it was hard for people to grasp that a government would target an artist—that an artist would be arrested for creating a painting. Our society has never experienced a dictatorship on our soil, has never seen civil liberties stripped away. So at times, it can be a challenge for American audiences to imagine how a dictatorship might begin and who would be perceived as a threat to such a regime.

Last year I wondered about the relevance of my play—wondering if a play depicting a historical moment in time in another country would resonate with a larger audience. However, in the past few months, the subject of the play feels relevant in a cautionary tale kind of way.

Not only is Ghost Limb speaking to our current political moment, it’s putting on stage a familiar story from the Latinx community. So many of the countries in Latin America have dealt with military dictatorships—the majority installed with the help of our own government—and dealt with state terror and oppression. And the disappearing continues today. This September will mark the third-year anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students in Iguala, Mexico who were arrested. They are presumed dead.

As a student of history, I know that state oppression in Latin America is directly tied to American intervention. For audiences unfamiliar with this history, I hope Ghost Limb will encourage people to examine not only the US’ role but how those dictatorships took hold. In Argentina when the military took over in the mid-70s, people there said “It can’t happen here.” And it did. Civil liberties were taken away and their country entered a dark time that still impacts their society 40 years later.

Trevor: Your grim Latino fairy tale cycle—The River Bride, Wolf at the Door, and Alcira—has been your most recognizable work. What have you learned about yourself as a playwright through both the creative process as well as the business side of things in terms of getting these plays produced?

Marisela: I learned as a poet that there are two sides to life as a writer: the creative side and the business side. I came to playwriting knowing that not everyone is going to say yes, but it’s a numbers game. The more you put your work out into the world, the better chances you have at finding success.

Like plays, productions don’t spring up overnight. Occasionally there might be a production offer that surprises you, but often for playwrights at the beginning of their career, there is a lot of work that goes into getting a production.

I’ve found that to get a production you need two things: 1) a play people like and; 2) producers who are interested in you and your work. And yes, they have to be interested in you AND your play because if they are going to commit to a production it’s not enough to like the play. I get it—who wants to work with someone for several months if the working relationship is strained or difficult? People want to work with people they like. So a theatre wants to get to know a playwright a bit to ensure that working together will be an amicable process.

The big question is how do you get producers interested in you. Well, just like writing a play is a process that can take time and requires effort, so does building relationships with producers. Those relationships have to be cultivated and genuine, in my opinion. No one likes to be seen merely as a means to an end, so building real relationships with theatre peers is key. This production of Ghost Limb and my Chicago production of The River Bride both came from producers I’ve known for a while. My relationship with Halcyon Theater in Chicago especially is a good example of what I’m talking about because really it’s about my relationship with Tony and Jenn Adams who run Halcyon. I met Tony online via Twitter where we just talked about theatre with other theatre artists. Then came the day he asked to read one my plays. Then about a year later came the 2013 workshop production of that play and just this month Halcyon closed a production of The River Bride.

It’s true what they say. In theatre, it’s who you know. But the upside is you can always increase who you know. Now I’m an introvert which is why I like to use Twitter as a way of expanding my network. But I’ve also learned to make small talk in person—to really get to know the theatre artists in my community. For example, in the Bay Area where I lived for many years, I’ve gotten to know a fair number of directors, actors, and producers by being an active theatergoer and volunteer. You never know who is sharing your work, talking about you, or pitching your plays. So being an active member of your theatre community and being a professional (a.k.a. treating people well) will often result in people reaching out to get to know you and your work.

Lastly, it can take time. Playwright Adam Szymkowicz says it can take 10 years before you see traction in your career. So you aren’t failing at this if you don’t see immediate success. I’ve just past my 10-year mark and I’m seeing all the work I’ve put into that relationship building yielding results with new opportunities and work. So use your 10 years to hone your playwriting and to build a network theatre peers.

Trevor: In 2015 you began your MFA in Playwriting at the Iowa Playwrights Workshop. Can you tell us more about your experiences in the program? How has Iowa changed your work as a playwright? What have been the significant moments during your time in Iowa?

Marisela: Getting my MFA in Playwriting has been my first real opportunity to study theatre. I’ve really enjoyed the time diving deep into theatre history and theory.

I’m not sure that Iowa has changed my work as a playwright. That’s one of the strengths of the program; it doesn’t dictate a specific form that all the playwrights must adhere to (i.e. a strident adherence to the three act structure). That’s why Iowa playwrights each have such unique voices and sound sometimes radically different. What the Iowa Playwright Workshop does is try to help you hone your voice.

What has changed is my understanding of how I write. I’ve realized recently that my work is very centered on characters. Which I kind of knew already, but I have more clarity. You see, I struggle with just writing from a plot point of view if I don’t get to know my characters first. That means I need a clear idea of who they are and what they care about. When I write it’s like the characters are in charge, they write the play themselves and the world unfolds because I’m always exploring it through them. If I don’t know my characters well then they aren’t whispering lines of dialog in my ear and I’ve learned that I really need that or I feel very disconnected to the work.

One of the most significant moments was my second semester in the program. Ironically, I wasn’t on campus for most of this semester. But that was what was so remarkable. The Iowa Playwrights Workshop was very supportive of my desire to be present during the rehearsal process for the world premiere of The River Bride at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2016. The Workshop allowed me to do a residency semester which meant I was still in the program and still getting credit toward my degree, but I was off campus in residency at a theatre.

I felt very supported by the faculty—that they wanted to facilitate an opportunity for me to grow and learn as an artist. That production process was such a learning experience and such a magical time for me as an artist. And, as part of my residency semester, I had to keep a production journal to turn in for credit. I really love that journal and have adopted creating production journals for other world premieres as a way of documenting the process and identifying the key notes to give to directors who want to do subsequent productions.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Trevor Boffone.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.