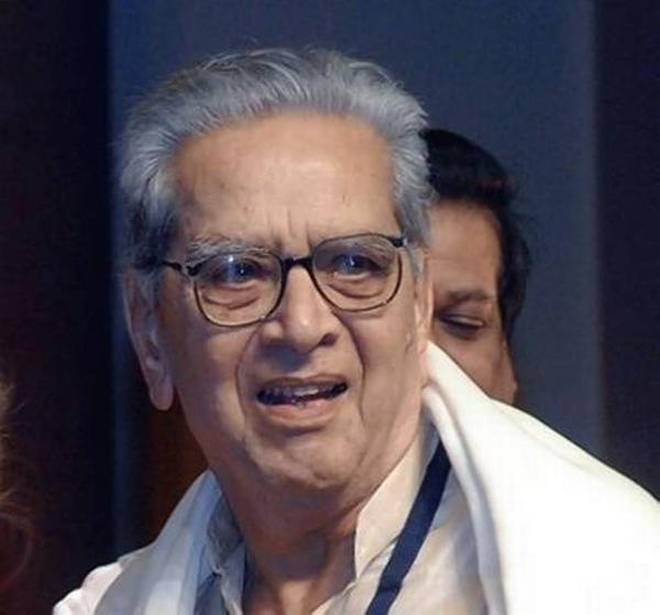

A staged legacy: Doyen of Marathi theatre, Shriram Lagoo gave life to political plays, worked in women’s welfare and left behind a mark few could rival.

Although widely acknowledged as a doyen of the Marathi stage, it was his parts in Hindi cinema that made Dr. Shriram Lagoo a household name across India. Acting was his chosen vocation, even if he never quite discarded his credentials as an ENT surgeon. From 1952 to 1969 he balanced his medical practice with forays into ‘progressive’ amateur theatre, before debuting in 1969 as a professional actor in Vasan Kanetkar’s Ithe Oshalala Mrityu, a historical play on Sambhaji Bhonsle. He was 42, no spring chicken, but a ready fit for the heavy-duty roles that were to come his way and soon become his calling card. One of Lagoo’s greatest parts for the Marathi stage was Natsamrat, the play by Kusumāgraj, which was first staged in 1970, and in which he played Appa Belvalkar, a fictional Shakespearean actor in glorious decline, opposite Shanta Jog. Another notable excursion was Kanetkar’s Himalayachi Savali (1972), in which he played (once again, opposite Jog) an early twentieth-century reformer modeled on Dhondo Keshav Karve, who had worked extensively in the field of women’s welfare. Then in G.P. Deshpande’s sharply political Uddhwasta Dharamshala, of which he directed the opening run in 1974, he played the Marxist professor Shridhar Vishwanath Kulkarni, called to task by a college tribunal for his political affiliations. In an article by Vidyadhar Date, Lagoo described the professor as a drummer who marched to his own beat — “He is a dissenter. Such men may fall by the wayside, but the society benefits from their ideals.” It’s a play that is strikingly relevant in today’s anti-intellectual climate. It must be said that recent commercial revivals of classic Marathi drama, like Kanetkar’s, play out more as signifiers of ‘Marathi pride’ than the political allegories of their time. As a director, Lagoo gave life to political plays like Vijay Tendulkar’s Gidhade, in which he also starred, and Ugo Betti’s Italian play Queen & Rebels, which he adapted into Marathi. Although he was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Acting in 1970 itself, he was conferred the Akademi Ratna for lifetime contribution in 2010.

In memorial

In his memoirs, And Then One Day, Naseeruddin Shah writes of how the effortless demeanor and delivery of stage legends like Paul Scofield or Shreeram Lagoo, convinced him that there was “absolutely no difference between good acting” in cinema or theatre. Shah also laments that the tragedy of great thespians like Lagoo and Nilu Phule was that “they would be remembered only for their performances in films thoroughly unworthy of them”, and known only as “excessive character actors they were compelled to be in popular Hindi cinema.” He goes on to say, “People unfamiliar with the output of these two theatre giants would be unable to imagine what they were capable of.” Of course, within the parameters of mainstream cinema, Lagoo wasn’t typecast in the way other ‘character actors’ like A.K. Hangal or David might have been, playing everything from shipping magnates to lawyers and judges, middle-class patriarchs and cuckolded husbands. Perhaps, one of his most memorable parts was in the forgotten Hrishikesh Mukherjee film, Jurmana, in which he played an upright professor who was gradually losing his eyesight, grappling with contemporary morality. In Marathi cinema, V Shantaram’s Pinjara, set in the riotous world of tamaasha, and Jabbar Patel’s Mukta, in which he played Abasaheb Kanase-Patil, a veteran of Maharashtra’s co-operative movement. In these films, he was a perfect foil to towering female protagonists, a role reversal of the position he enjoyed in his plays for the Marathi stage, in which the women were relatively peripheral.

Another legacy that Lagoo leaves behind is that of a vociferous advocate of freedom of speech, taking up cudgels for banned plays like Kiran Nagarkar’s Bedtime Story, an irreverent take on the Mahabharata that was written during the Emergency, and Pradeep Dalvi’s Me Nathuram Godse Boltoy, albeit a play he did not agree with ideologically.

This article was originally posted at The Hindu and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.