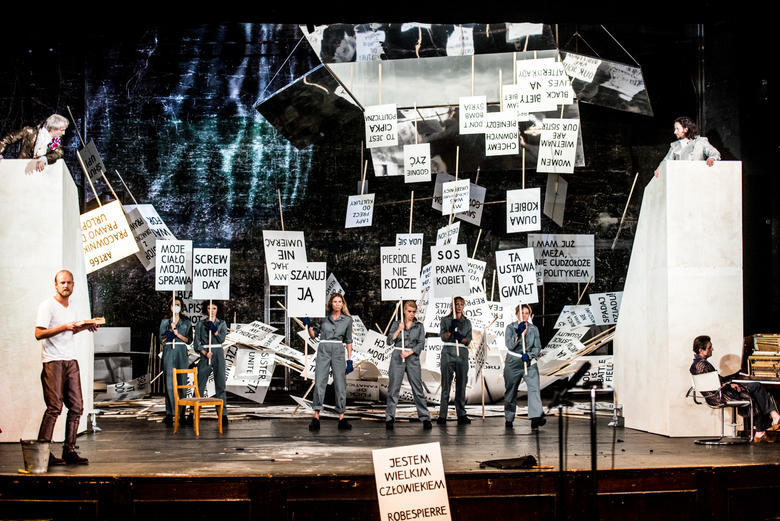

“Auto-theatre” that I have described recently and that remains at the core of new political theatre (including the newest productions that appeared in the field, i.e. Stateswomen, Sluts of Revolution, or the Learned Ladies by Jolanta Janiczak and Wiktor Rubin, that premiered in October at Teatr Polski in Bydgoszcz or last edition of the Microtheatre at Komuna Warszawa, created in November) is interestingly situated within the context of questions posed by contemporary performing artists in Europe. Investigation of methods, principle, and mechanisms of theatre production, as well as questions about the relationship with the audience, have all been in the center of attention of such artists as Xavier Le Roy, Jérôme Bel, Eszter Salamon, Ana Vujanović, Ivana Müller, Everybody’s Collective, Mårten Spångberg and much more. Their choreographic and theatrical practices are conspicuously political, but, in contrast to Polish examples, they are predominantly realized outside the repertory theatre.

At the same time, “auto-theatre” in Poland functions alongside the debate on the working conditions of artists and art producers that have been going on for years now in Polish visual arts. Alongside numerous texts and artistic interventions, projects distinctively thematising the institution (such as, for example, Winter Holiday Camp at Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw or Towards a Critical Institution at Arsenal Gallery in Poznań) and the question of politically of art (e.g. the cycle Effectiveness of Art at the Museum of Art in Łódź), publications exploring the mechanisms of production in art as well as working conditions of artists and art workers have also appeared (among others, The Black Book of Polish Artists, The ABC of Projectariat). It is discussed by Agnieszka Jakimiak in her text Nothing to be Ashamed of at „Dwutygodnik”; in the festival catalogue, we also publish an excerpt from The Art Factory report, drawn by Michał Kozłowski, Jan Sowa, and Kuba Szreder, analyzing the socioeconomic status of contemporary artists and producers in the visual arts.

Meanwhile, current political scene, radically crosscut by divisions which seem increasingly less likely to be overcome, considerably hinders the debate around theatre. Joanna Krakowska claims that “auto-theatre” is also an attempt at “renewal of communication that has been disrupted in theatre due to too hermetic artistic quests, and in public life – due to radical political divisions and ideological polarity, precluding any discussion.”

This seems even more important in a situation when raising controversial subjects that might turn out to be a bone of contention in theatrical milieu and lead to new divisions is highly unwelcome. It concerns, inter alia, the question of payroll, internal relations within the company, subjectivity of creators and co-creators of spectacles – putting them forward them places one at risk of community ostracism, contempt, ridicule. Because it is so auto-thematic and dull, because why get involved. Because suddenly the space for opposition ceases to be obvious, the adversary clearly defined and, with relief, placed at the opposite end of the political scene. Because why talk about it, there are other and more important problems. Meanwhile, there are no questions that are more crucial. And the new Polish theatre puts them forward, for instance by directing the debate around theatre towards the most basic topic regarding working conditions. I am convinced that nowadays one cannot practice political or critical theatre without discussing the methods and modes of production and the subsequent consequences for workers – always with reference to the context of late capitalism and its mechanisms, within which we operate. Otherwise, democratic slogans, most aptly theorized and thematised, will remain painfully empty.

This post originally appeared on the East European Performing Arts Platform on May 24th 2017 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marta Keil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.