A couple of weeks ago, I moderated an inclusion panel at the Edinburgh Film Festival where I interviewed two disabled filmmakers about their work. During the question and answer session after the talk, one of the filmmakers mentioned how, with regret, he hadn’t been able to caption a short film he’d made, because of budget issues and the fact he’d worn his editor’s patience out.

He was then quite heavily challenged about this by an audience member. Fair enough. I need captioning myself, so I wasn’t going to disagree. However, what occurred to me, and what I said soon after, is that I’ve been in lots of situations where a deaf or disabled person or organization is being challenged about access, but far less often have I been in a situation where a mainstream (or non-deaf or disabled) person or organization has been challenged for the same.

I was at a festival where I could see very little access, in the form of subtitles, on the mainstream films. Nor was there (as far as I could see) any way of finding out which films might be subtitled out of an extensive program. Which was ironic, because access was the reason I was there.

I didn’t want to go all the way up to Scotland and not see anything, so I went to see three films and fell asleep in two of them because I couldn’t understand them. I found myself watching the shooting style but having little idea of the story. Yet it was a disabled filmmaker − and not any of the mainstream organizers or filmmakers − who was the one being challenged in front of an audience for not providing captions.

Which makes me wonder − do deaf and disabled organizations and individuals shoulder a bigger share of the access responsibility than mainstream organizations and people? And if so (and I’m pretty sure it is), is this fair?

In my experience, deaf and disabled individuals and organizations are generally far more aware of access needs and take far more effort − in planning, time, and money − to provide access than mainstream organizations do.

I’ll give a few examples:

- When I worked at the BBC2 Deaf program See Hear, a large part of the production schedule and budget was given to adding in-vision interpreters to the program and getting the program subtitled. This was something other BBC shows didn’t have to give time or budget funds for. Having to teach hearing production staff deaf awareness skills was also another additional aspect of work for the Deaf team members on the show.

- Deaf and disability theatre companies will often provide far more access for deaf audiences (through captions and BSL interpretation) sometimes at every performance. They may employ extra actors on stage to provide voiceover or double up with deaf actors. During rehearsals, they may employ interpreters or other communication support. Some of this may well be budgeted for or paid for through Access to Work, but it’s still extra work for the existing staff to set up.

- Disabled performers are, in my experience, much more likely to schedule a BSL interpreted performance or captioned show, one example of this is Adam Hills, the disabled comedian, who often books an interpreter.

- Deaf and disabled organizations such as charities are far more likely to consider access, for example by making BSL videos with information on their website, or booking communication support at meetings or events.

- Festivals such as Deaffest or DadaFest provide far more access for Deaf people than mainstream festivals. (This might seem obvious given their deaf audiences, but even so, it’s still worth taking into account)

- Several disability podcasts, including BBC Ouch, provide transcripts of what was said in their shows. Very very few mainstream podcasts do.

- Deaf filmmakers will nearly always subtitle their films so that they can be understood by non-signers. This takes extra time and effort and may incur extra costs.

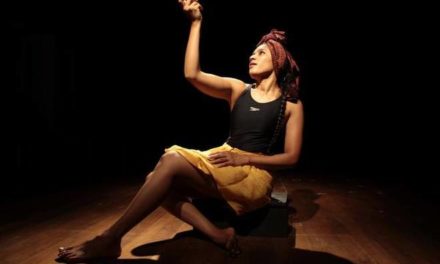

Claire Hill providing live captions of Vital Xposure’s “Let Me Stay” |Photo Credit: Disability Access Online

There are many more examples like the ones above. What strikes me about all of this is that it’s not really recognized or taken into account.

How simple it must be, to be a mainstream individual or organization, not needing to take access into account at all. No extra people to schedule, no extra costs to budget for. You could just think about the content of the TV program you’re making, send out your short film once it’s cut, rehearse with a bunch of actors in one language and send your small cast for a play out on tour.

I’m not looking to give people excuses, I’m all for asking deaf and disabled people and organizations for access (if it’s not already provided) and for giving constructive criticism when access is not there. But we really need to be asking mainstream people and organizations for access and challenging them far more than we currently do.

Otherwise, what’s really happening in some cases is that deaf and disabled people and organizations are being given a far, far harder ride than non-deaf and non-disabled groups are. And that’s not really right, is it?

This article was originally published on Disability Arts Online. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Charlie Swinbourne.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.