During the opening ceremony of the 32nd edition of the Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theater (CIFET, 1-8 September), Egypt’s Minister of Culture, Ahmed Fouad Hano, proposed renaming the festival to the Cairo International Theater Festival. The suggestion reignited long-standing debates about the identity and future of one of the Arab world’s most significant cultural events.

At first glance, it might seem like a minor semantic shift. Yet, for many, the name carries weight — tied to the festival’s legacy, mission, and cultural symbolism. Is such a change warranted, or even necessary? Before taking a firm stance, it’s worth examining the festival’s origins, evolution, and the broader meaning behind the word “experimental.”

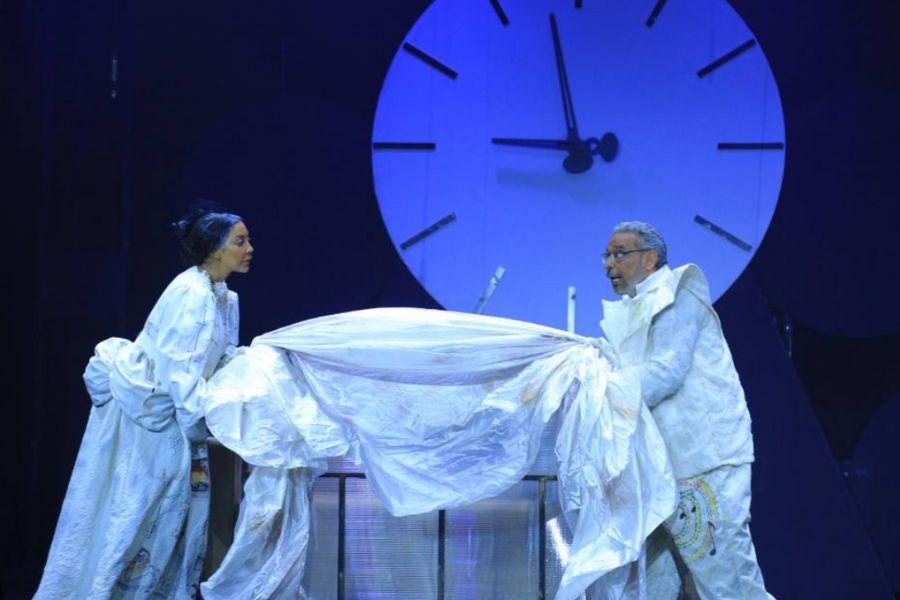

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

Question of Legacy

Founded in 1988, CIFET quickly became a key player in the Arab theater scene. While most regional festivals focused on classical and traditional works, CIFET stood out by embracing experimental, interdisciplinary, and avant-garde theater. It welcomed unconventional forms—from physical theater and multimedia installations to site-specific and post-dramatic works.

CIFET was not solely a top-down state initiative; it also emerged in response to the growing momentum of Egypt’s new theater movement in the 1970s and 1980s. University stages, informal venues, and grassroots troupes like El-Warsha and The Temple experimented with radical storytelling. They rejected state theater conventions and sought new platforms for creative expression.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

However, as the following years revealed, the festival struggled to fully embrace the very community that in a way, has partially inspired it—capitalizing on the experimental label while rarely integrating its grassroots Egyptian representatives.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, CIFET became a hub for artistic exchange, welcoming performances from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The festival showcased a diverse range of theatrical forms, mostly experimental. Importantly, it provided a platform for Arab artists to take creative risks. This was especially true during periods when the theatrical scene in parts of the Arab world—particularly the Gulf—was still emerging.

In addition to performances, the festival hosted symposia, workshops, and academic panels, adding an intellectual dimension that positioned CIFET as more than a showcase. It became a space for discourse, training, and creative exploration.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

By the early 2000s, the festival had become a high-profile, resource-intensive state project. Its stages were dominated by international spectacles, many high-budget productions — often designed more to impress than to challenge — and not always aligned with the artistic expectations of theater scholars and practitioners. More often than not, the festival’s opulence stood in contrast to its experimental ethos. This was clear in lavish opening ceremonies, guests staying in five-star hotels, VIP receptions, and strong promotional campaigns.

With the growing number of performances—sometimes reaching up to 60 shows over just 10 days—it was possible to discover a few standout gems. However, the sheer volume also meant a noticeable number of productions with less refined artistic quality.

Political changes following the 2011 revolution led to funding cuts and shifts in cultural policies, ultimately bringing this trajectory to a halt. CIFET was suspended and, when it returned in 2016, it did so on a much smaller scale—with a reduced budget, fewer performances, and a non-competitive format.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

“Contemporary” versus “Experimental”

When the festival was revived in 2016 under the leadership of theater-maker and academic Dr. Sameh Mahran, it returned with a revised name: the Cairo International Festival for Experimental and Contemporary Theater (CIFCET), as the event’s 23rd edition. The addition of “Contemporary” was meant to acknowledge the festival’s expanding scope, embracing not only boundary-pushing works but also modern theater that reflects current themes and aesthetics.

However, the theater community responded with mixed feelings—expressing not only symbolic concerns but also conceptual confusion—about pairing “experimental” with “contemporary.” Many critics pointed out that the terms are not equivalent: “Experimental” refers to a methodology—a philosophy of innovation, rule-breaking, and aesthetic exploration—while “Contemporary” refers to time, encompassing any work created in the present regardless of whether it challenges norms.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

As such, the name seemed to blur the festival’s identity. Was it a platform for formal innovation or simply a showcase for current theater trends?

In 2020, under the presidency of playwright and academic Alaa Abdel Aziz, things were difficult for the festival and any cultural activity due to the lock-down accompanying the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, Abdel-Aziz limited the festival’s 27th edition to showcasing local live performances by Egyptian troupes and presenting international plays through online platforms.

Most importantly however, he reinstated its original name and competitive nature: the showcase returned as the Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theater (CIFET) — a decision widely seen as a return to its authentic mission.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

Does “Experimental” Still Capture the Festival’s Mission?

Yet the question persists: Does the term “experimental” still serve the festival’s evolving role? According to Minister Hano, experimental theater would remain a “core component,” but under a more inclusive umbrella — one that may invite broader participation and greater public engagement.

Dr. Sameh Mahran, who returned as CIFET’s president in 2024, acknowledged the ongoing debate about the festival’s name and scope in an interview for Ahram Online. He noted that the term “experimental” is increasingly being replaced by “performance art” globally. He too leans towards changing the festival’s name to Cairo International Festival for Theater, with a dedicated branch for experimental work, aiming to attract a broader audience by including various genres like comedy and musical shows.

In one of her interviews, CIFET Director Dr. Dina Amin emphasized that experimental theater is not just a style but a philosophy: “It’s about challenging norms, rethinking the relationship between performer and audience, and testing new forms of storytelling.”

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

This stance moves toward addressing the core question: Even if the festival continues to embrace experimentation, does the word “experimental” need to remain in the title?

Younger advocates for a name change argue that the label can be intimidating or misunderstood, often associated with obscure or inaccessible work. This may limit audience reach or alienate artists who innovate in content but don’t identify with the “experimental” label. A broader name could increase inclusivity and attract new collaborators. It would also better adapt to the technological and creative challenges of the 21st century—including the integration of digital tools, AI, and hybrid forms.

On the other hand, critics worry that removing or replacing the term could lead to mission drift. Without “experimental” as an anchor, the festival risks becoming just another international theater event, losing what once made it distinct—its spirit of risk-taking.

But with the region’s theatrical landscape rapidly expanding and evolving over the past two decades, do we want to stay distinct, or do we want to embrace a broader community? What is the right balance for honoring CIFET’s origins while welcoming growth?

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

Beyond Semantics

Ultimately, the debate is not just about terminology. It reflects deeper questions about the festival’s future. Can the festival evolve without compromising its identity? And is the name a help or a hindrance in achieving that balance?

Perhaps the focus should shift from what the festival is called to what it stands for. As Minister Hano said in his opening speech: “Let Cairo remain a platform for art and culture, and let theater in Egypt and around the world continue to be a space for creativity.”

If the festival’s mission remains to expand the boundaries of performance, nurture local talent, and facilitate intercultural exchange, then its structure, curation, and support systems matter more than its title. Yet, for many artists, the name remains a powerful symbol — one that communicates the festival’s core values to the world.

Whether CIFET continues under its current name or adopts a broader one, the challenge ahead is clear: to evolve meaningfully within the vision that has defined it for nearly four decades.

Workshops, seminars, and performances of the 32nd Cairo International Festival for Experimental Theatre. (Photos: Courtesy of CIFET).

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ati Metwaly.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

![Between Life And Death: A Festival’s Journey Through Tragedy [Part I]](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Picture4-1-440x264.jpg)