Remar, An Improper Destination, written and directed by Mariano Saba, premiered at the Sportivo Teatral in 2017 and is being mounted again, for its second season, in the same theatre. Remar won the 5th Edition of the Artei Prize for independent theatre production, and Odyssey Double Par (A Farce Of The Empire), the work’s antecedent, also authored by Saba, received mention in the Casa de las Americas Literary Prize in 2016.

Remar, An Improper Destination is a tragicomedy based on the crossing of the Odyssey but takes place in the El Tigre Delta in Argentina. The two rowers belonging to El Gallo Fiambre Boat Club have accepted the challenge of the Canottieri Italiani, which entails competing in a clandestine regatta. Midrace, a storm has blown them out of the delta, and they are lost in what they believe to be the Atlantic Ocean. Poseidon (Gustavo Sacconi), lost in a rage of revenge against Ulysses, encounters the two rowers and thinks they are Ulysses’ oarsmen. Poseidon’s desire for revenge is rooted in his son Polyphemus’s blindness, inflicted at the hands of Ulysses. Poseidon appears at the beginning of the work, costumed in a fish head and a tunic-wrapped net, and proclaims:

I am Poseidon, god of the seas, I am the father of the Cyclops Polyphemus! [Crosses to the front of the stage] And these rowers have left my son blind. In a few minutes, I will enter the scene in human form as to confuse them and make them wander forever…What am I going to do? I have to punish them never to be forgotten!

This call to action thus converts audience members into accomplices, as only they know of the tragedy to come. Poseidon then transforms into Anuk, a cheating, crooked investor from Alaska, and he fulfills his proclamation. Poseidon disrupts the course of the rowers; not even technology can set them aright–it just doesn’t work.

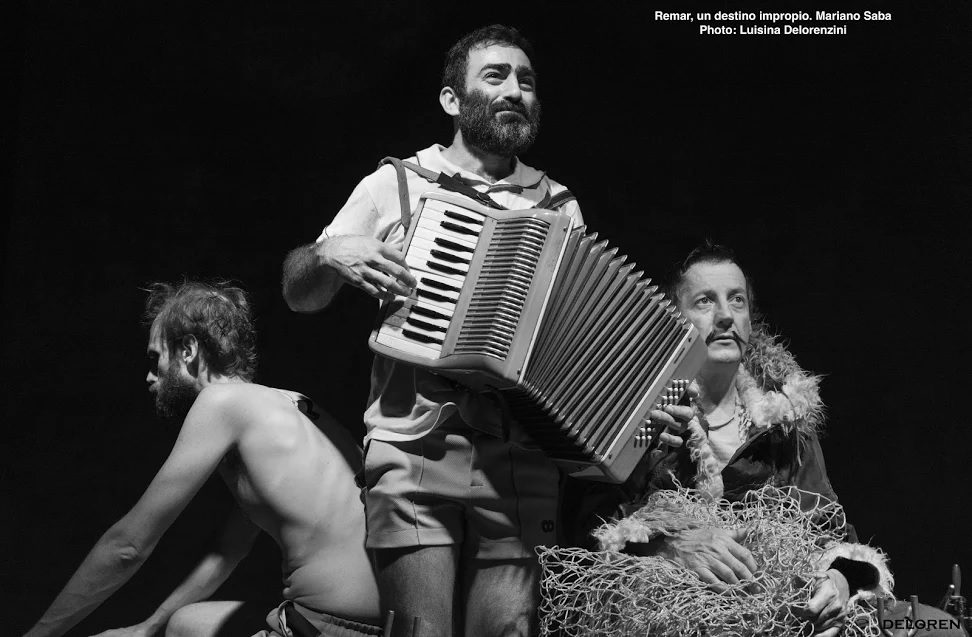

Remar does not attempt to create this verisimilitude onstage. Such fantasies as crossing turbulent waters during a raging storm (sound and lights by Ricardo Sica) are brought to life under the close direction of Saba and his ensemble. The gaze of the two oarsmen, Boris (Hernán Melazzi) and Rawson (Mariano González), transports us to the maritime space. Our perception of the real and the unreal is just as lost as the boat in the storm, coupled with clouds of fog. Poseidon appears in the theatrical space, breaking the fourth wall, speaking directly to the audience members and making them accomplices of his revenge, in a nod that suggests the current political reality of Argentina.

The play demands, from its audience, a heightened ability to suspend disbelief. We are persuaded to play along with Saba and his ensemble and quickly settle into this theatrical fiction. At the end of the play, however, when the distance between the unreal and reality begins to close, we understand that these rowers are paddling, trying to find Ithaca in the Argentinian present. This political play also showcases the insufficiency of technology, now praised as the solution for everything; in the tragi-comic fantasy, technology fails when it is most needed. Moreover, so, Saba relies on the presence of the body: “the poetic inscription of the bodies, in the middle of a game of speeches, in a world that bets more on the absence than on the presence” (Página/12, July 27, 2017).

The metaphorical link–quite clear for Argentinean spectators–with history and Argentine idiosyncrasy is achieved thanks to some quite obvious winks. Rawson is the one with the voice of command, whereas the Russian is just a carpenter who has been hired for the regatta because his income is insufficient; this situation forces him to take any job that might help him survive. The scam of selling a non-existent piece of land also seems to point to a “Creole-smartness,” along with the search for some way to operate the battery-dead communication devices.

Saba compresses this fantasy into just fifty-nine minutes, mostly consisting of scenes justifying the subtitle “improper destination.” The constant paddling and paddling and paddling, with no arrival, is a reflection of Argentinian history and politics. The play jumps through time from Ancient Greece to the 1950s to the present day– the mid-twentieth-century costuming of the rowers is juxtaposed with the present, with Boris using the Internet.

Although Remar offers a dark, dystopian look at Argentina’s future, it is delivered with humor through the use of the absurd. The games of colloquial double meanings produce funny dialogue; a much-needed sense of catharsis transpires within an audience struggling with a similar reality.

The subject matter of Remar, An Improper Destination places it among the best of current Argentinian political theatre. In the colloquial Argentine language (and eighteenth-century English), “to row” means to fight against the circumstances, to resist the difficult times, and to continue forward despite all. The rowers resist and “row” with precise and constant movements, resisting and un-resting. Saba and his play tell of the anguish that festers when “the discarding of the most deprived areas” happens “cyclically” in Argentina. Subtly, this production poetically expresses the Argentinian present and the distress that deprivation generates in broad sectors of society.

For the connoisseur of Argentinian history and for those aware of the current neoliberal reality, the character of Anuk is a familiar one. He is an investor who cheats, one who purposely leads the rowers astray, certainly not to Ithaca. Anuk embodies the investors who, according to the current government, would take the country out of economic turmoil and fix the policy that has sunk it.

Mariano Saba, in a statement to the newspaper La Nación, said: “Argentina is stuck in cyclical idiosyncrasy that falls back into tragedy and error and later returns to redeem itself because it has some power to rearm.”

These fictional paddlers and millions of Argentinians will never reach Ithaca, but they will forever keep paddling as they are fueled with hope and equipped with an unwavering resilience to survive.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lola Proaño Gomez.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.