Dulaang UP’s current production, Rody Vera’s Filipino adaptation of Faust, directed by José Estrella, at once seeks to stay true to the spirit of and attempts to contemporize Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous Manichean drama that was resolutely rooted in the Romantic vision of its own time.

Faust. Karen Gaerlan as Margarita, Neil Ryan Sese as Faust and Paolo O’Hara as Mephisto. Photo: Dulaang UP)

This was a vision that, as with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, cast a nostalgic look back on the pre-industrial and pre-Enlightenment life of folkloric Europe, viewing with suspicion modernity’s unbridled investment in materialistic rationality. National literatures—and modern nations—were of course at this time themselves being steadily consolidated and solidified, accompanied by and alongside the establishment and spread of print literacy across increasingly discrete national boundaries and classes.

A reinscription of the Biblical Job, Goethe’s extended dramatic poem saw the pursuit of worldly knowledge as being inherently spiritually dangerous and fraught with metaphysical peril. The story of the moral ruination and eventual redemption of the innocent Gretchen (here renamed Margarita, after Mikhail Bulgakov), all because of the venality of the erudite and intellectually insatiable scholar and alchemist Faust, was Goethe’s way of dramatizing the same ethical quandary that lay at the heart of Shelley’s paranoid Gothic novel about the potential monstrosity of human ingenuity.

And yet, the spatial and temporal localization of this Romantic allegory, in this latest offering from the foremost theater company of the University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD), seems unwittingly caught in a self-contradiction, one that proves, on hindsight, productive in a not entirely foreseeable sense: ironically, the same longing for folkloric value is what actually confounds the urgent sense of righteous indignation that this production seeks to elicit in its audience.

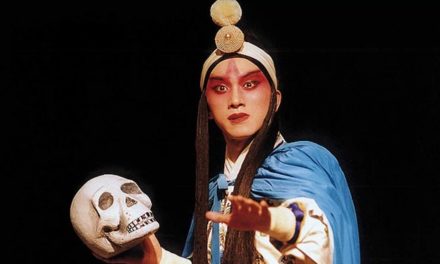

<Faust. Jack Yabut alternates with Neil Ryan Sese as Faust and Mailes Kanapi alternates as Mephisto with Paolo O’Hara. Photo Credit Adrian Begonia

Thus, even as José’s production distinguishes itself in cosmologizing the everyday evil of the Philippines’s current state of affairs—rendering as blatantly Mephistophelian, for example, the potty-mouthed and murderous national leadership, as well as its phalanges of iniquitous mercenaries, allies, apologists, and trolls, whose sequential sound bytes and appearances on the stage of UPD’s Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater were met with raucous applause and uncomfortable if self-ironic laughter—this message is diluted by the play’s own declared investment in the desire to return to the folkloric past, which in our case is precisely what makes the passing of stern judgment difficult.

From another angle, the play’s central story is a cautionary one: of how the life of a virtuous maiden, all because she has allowed herself to love and desire and have sex out of wedlock, is spectacularly ruined, almost to the point of hopelessness. This proves hardly relatable to the contemporary Filipino viewer, all too aware as she or he must be of how even the most publicly libidinal forms of scandalization in our case have not, in fact, ruined the lives of the women who were unfortunate (and, like Gretchen, gullible) enough to be involved in them. As we only too keenly know, these contemporary Filipinas have even ended up marrying well, and are presently, to all intents and purposes, upstanding members of their respective professional communities.

This is because the folkloric in our case isn’t—unlike in Goethe’s Europe, effectively Christianized as it had been for more than a millennium by the time this play was written—securely dualistic and therefore ontological in its cognitive predisposition. By contrast, our culture remains residually and powerfully oral in its most basic character, and this effectively makes it difficult for us to commit ourselves to the absolutes of the categorical mentality from which Goethe’s lyric vision derived its ethical and dramatic energies.

Faust. Karen Gaerlan praying to the Mater Dolorosa (performed by Ina Azarcon-Bolivar). Photo Credit Adrian Begonia)

In other words, the effect that Goethe sought—of sympathy for the ignorant and the misled victim, and suspicion and/or derision for the clever and the cynical victimizer, who is finally more the devil than the man—was grounded in the metaphysical tradition of his own time, and therefore easy enough to achieve among the audiences of his own culture, which was already well acquainted with (and entirely imbricated in) the moral and ontological dualisms of Judeo-Christian thought.

Adapting such a vision to our contemporary circumstances—which was the obvious intention of this production—can only be fraught and difficult proposition, one that is more likely to fail than succeed. Indeed, this would seem to have been the case on the day that we saw it, the assembled audience being fundamentally unmoved by what appeared to be an anachronistic morality tale, which not even the numerous and pointed allusions to horrific current events—extrajudicial killings, antiheroic reburials, etc., all visualized as the grotesqueries that they veritably are—could render emotionally and dramatically relatable.

The decision to abridge the original two-book play—which was both unfortunate and, given the logistical and time constraints, unavoidable—also didn’t help clarify Goethe’s Romantic vision, which pitted worldly knowledge and rational advancement against traditional religiosity on one hand, but on the other, in the play’s full version, also yearned for and gestured toward an older, more unitarian, and pre-Christian spirituality.

This was, for Goethe, an immemorial and possibly pagan or animist form of spirituality that transcended the Madonna/Whore, Heaven/Hell, and Virtue/Sin dualisms that afflicted even the folk knowledges of his own time, and could in fact imagine it perfectly possible for a child-murdering—in our own language today, abortive—mother like Gretchen to deserve eventual redemption.

This is because her transgression is that she simply acquiesced to the desires of her body, which cannot be corrupt but is—within the Romantic purview, in which Nature became the surrogate for the discredited God of institutional religion— entirely self-evident, given, and therefore inalienably divine. In envisioning Gretchen’s spirit being lifted up from despair to salvation, Goethe arguably taps into at the same time that he revises the Mariological mythology to which he himself is heir, and reacquaints it with an “earthier” and more compassionate understanding of the Divine Feminine, that antedated the arrival of the cult of the Virgin in Europe (as would later on be archeologically revealed in the recovery of sculpted Paleolithic images of feminine fertility, the most famous of which being, of course, the Venus of Willendorf).

Despite this unprocessed thematic complexity—that Vera’s script fails to dramaturgically take into account—José’s production undeniably has its strengths. Even as the first act could’ve been better reconceptualized and edited to a more effective length, the play is audiovisually arresting and choreographically interesting enough for the most part, and the performances of the cast are—as is the case with many of Dulaang UP’s semestral offerings—pretty earnest and, in the main, competent and strong.

Also, there may be some casting “oddities” here and there—especially the choice of a pudgy and mature-looking Faust, whose transformation from slovenly and decrepit scholar to young dapper and virile lothario could’ve been sharper—but they didn’t finally detract from the drama, and arguably even nuanced it. To wit: the all-too-visible misalliance in terms of chronological age between the central characters added an additional layer of perversity, that was certainly germane to this morality play.

Special mention needs to be made of the lovely Karen Gaerlan, who memorably enfleshed her Gretchen (Margarita) with equal measures of vulnerability, eroticism, and dignified insanity, as well as Paolo O’Hara, whose rowdy and gauchely potbellied take on the deal-making devil Mephistopheles was spot on, especially given the script’s avowed intention to register its harsh but timely political critique (sadly, at the expense of a deeper understanding of and more critically translational engagement with Goethe’s thematically challenging and complicated work).

Dulaang UP’s Faust runs at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater up to the first week of March. Faust is part of the Salaysayan: K’wentong Bayan, Kaalamang Bayan, a festival of folk narratives or UPD’s celebration of the National Arts Month.

J. Neil Garcia is a professor of comparative literature at the University of the Philippines Diliman Department of English and Comparative Literature.

This essay published online via GMA News Online on 27 February 2017. Reposted with permission. To read original essay, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by J Neil Garcia.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.