Audiences laughed throughout Ko Sun-woong’s new work Heungbo-ssi (written and directed by Ko Sun-woong, pansori music and libretto by Lee Zaram, National Theater of Korea Daloreum Theater, April 4–16, 2017). After his previous piece Madame Ong (premiered June 2016) succeeded domestically, it traveled to France, promoting Korean changgeuk—sometimes called Korean opera—abroad. Ko appreciates pansori and has experience directing musicals and operas. Still, it is remarkable that his two changgeuk productions have caused such a sensation since he does not fully understand the genre. Heungbo-ssi and Madame Ong are not original works; they are based respectively on one of the five major songs and a lost piece in the oral pansori repertoire. Nevertheless, Ko created entirely new dramatic threads in these epic songs through his directing and selection of themes. Traditional narratives, often regarded as dull and shoddy, find new life through adaptation. However, Ko’s handling of these important cultural texts is also controversial as the novel elements of Heungbo-ssi ends up muddling changgeuk’s generic features rather than creatively expanding its boundaries.

Combining the “Eyes” with New Stories

Heungbo-ssi is structured around the “eyes” of the original pansori epic Heungbo-ga, adding other Korean folk songs and original music for the newly written scenes. [Translator’s note: In pansori, the “eyes,” or noondaemok, refer to segments that are considered central to the epic song in a narrative or musical sense.] The adaptation follows the original’s storyline: Heungbo is kicked out of Nolbo’s house, but remains kind to his spiteful brother. However, the production drastically renovates Heungbo’s journey. Although technically not a jukebox musical, the piece incorporates other musical elements to complement the famous eyes of the original.

The traditional story begins with Nolbo telling his brother and his family to leave without providing any background information about these characters. Heungbo and his ten children have nothing to eat and try their luck as peddlers to survive. When that fails, Heungbo goes back to Nolbo’s house to beg for food, but is assaulted physically by Nolbo and his wife. Dejected and hungry, Heungbo’s family contemplates death. But then, a Buddhist monk appears and guides them to an empty lot, telling them to move their thatched-roof hut there. One day, Heungbo rescues a baby swallow nesting in the eaves of his new home. Thanking Heungbo’s family, the swallow migrates south before winter comes and brings a gourd seed the next spring. Heungbo plants the seed—anything to ease the constant hunger. Within days, the seed grows into a cluster of giant gourds. The family cuts the gourds open, thinking they could scrape the insides for some meager nourishment. But the first gourd produces rice and money, the second gourd silk, and the third gourd a company of strong men who build a fine palace over Heungbo’s hut.

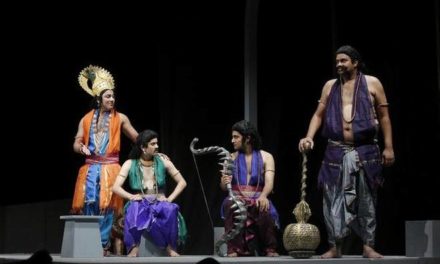

Heungbo-ssi, written and directed by Ko Sun-woong. Photo courtesy of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea.

Hearing rumors of Heungbo’s sudden fortune, Nolbo visits his brother. Nolbo learns about the swallow and the gourd seed, and goes back home to wait for a swallow to come. But when no danger befalls the hatchlings in his house, Nolbo impatiently breaks one of the swallows’ legs to “help” it. The next spring, the injured swallow brings a gourd seed of revenge. The greedy Nolbo plants the seed, but his gourds belch forth a host of lowlifes who consume Nolbo’s wealth. The fourth gourd conjures Zhang Fei—a mythical figure borrowed from the Chinese classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms—to punish Nolbo’s malice. Nolbo faces execution when Heungbo rushes in, quelling Zhang Fei’s rage with his brotherly love. Nolbo is also moved by his brother and repents, concluding the tale.

Heungbo-ssi uses major eyes from the Dongpyunje Heungbo-ga sequence, such as “Nolbo’s Malice,” “Heungbo’s Plea,” “Heungbo’s Beating,” “Taryong of the Monk,” “The Swallow’s Journey,” “Taryong of Poverty,” “Taryong of the Gourd,” and “Taryong of Silk.” To this solid backbone, it adds traditional funeral and farming folk songs, as well as new pansori songs and extant songs with rewritten lyrics. Ko’s adaptation also introduces the brothers’ parents, who do not appear in the original, and fleshes out characters such as Heungbo’s wife, his children, the swallow, and the monk. As such, this version of Heungbo’s tale places more emphasis on the story than the eyes. New scenes about Nolbo and Heungbo’s birth, Heungbo’s wife’s past, their children, the swallow, and the monk help the original story make more sense, but also depart from the source material in questionable ways.

When the curtain rises, we see a man named Yeon Sang-won (played by Kim Hak-yong) and his wife Hwang (Kim Cha-Kyung) instead of Heungbo and Nolbo. This couple was childless—that is, until Yeon finds a baby abandoned under a wild rosebush. At the same time, Hwang gives birth to a bastard child from another man. These two children become Heungbo (Kim Joon-soo) and Nolbo (Choi Ho-sung). Although neither child is of his blood, Yeon accepts them as his sons. He makes Heungbo the older brother because he was found first. The main story begins when kindhearted Heungbo heeds Nolbo’s complaints and lets him be the older brother. Nolbo demands written proof of his primogeniture, asking Heungbo to sign a contract. Oblivious of this change in sibling order, Yeon dies leaving his entire fortune to his first son. Nolbo also discovers that Heungbo was adopted and expels him from the family.

While Nolbo is scheming, Heungbo comes down from the mountains after mourning his father for three years. On the way, he rescues Jung (Lee So-yeon), a young woman exiled from her home because she is barren, and takes in a crowd of starving beggar children (Lee Yeong-tae, Nam Hae-woong, Kim Geum-mi, Kim Hyung-chul, Lee Kwang-won, Park Sung-woo, Kang Tae-kwan, Kim Yoo-kyung, Lee Yeon-joo). Suddenly, Heungbo is a husband and father. These events add specificity to Heungbo’s good nature, but some of the scenes feel jarringly out of place, such as when Jung is chased by a ravenous tiger (Woo Ji-yong) or when nine vagrant children instantly accept Heungbo and Jung as their parents.

Heungbo-ssi also changes the monk to a space alien and the swallow from the actual bird to a swindler preying on rich, married women (known as “swallows” in Korean slang). The timeless fable becomes fanciful and worldly in this adaptation. Humorous as they may be, these changes serve the production’s themes. The space monk (Cho Yoo-a) sings about relinquishing worldly desires, while the gourd gifted by the greasy charlatan (Yoo Taepyongyang) suggests spiritual nourishment. The image of Heongbo’s family cutting open the huge gourd while singing the Christian hymn “I’ve Got Peace like a River” was both hilarious and oddly cheesy. Traditionally, Heungbo gains wealth at the end of the story. But the main character of Heungbo-ssi gives up material wealth for spiritual fulfillment, an idea that does not exist in the original pansori. Moreover, a local government official appears instead of Zhang Fei to punish Nolbo, so that Nolbo brings about his own downfall rather than being redeemed by his brother. Moving beyond the original epic’s themes of brotherly love and good triumphing over evil, Heungbo-ssi explores universal love for humanity and a critique of materialism.

Heungbo-ssi, written and directed by Ko Sun-woong. Photo courtesy of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea.

The stereotypical servant figure Madangsoe (Choi Yong-suk) appears at the end, encouraging audiences to be good like Heongbo and capping the show with the famous unintelligible phrase: “duhjil, duhjil.” This epilogue reminded me of Heo Kyu’s 1982 changgeuk version, which attempted to revise the implausible setting and worn-out themes of the original pansori by presenting Madangsoe as a social commentator. As I have written elsewhere, Madangsoe reminds audiences that we should strive for goodness because happy stories like Heungbo’s don’t happen in the real world, resulting in a more theatrical changgeuk adaptation of Heungbo-ga than its predecessors. [1] Ko’s version is in line with Heo’s thematic focus on goodness, but creates new meaning by casting Heungbo as someone who distances himself from material wealth. Unlike Heo’s version, however, Heungbo-ssi’s dense plot leaves little space for audiences to appreciate the original pansori’s great musical segments. It was unfortunate that audiences were too busy following an ever-expanding plot. In other words, Ko’s witty and diverse story elements weakened changgeuk’s generic foundations as musical theatre. While Ko’s approach to playwriting—branching plots and dynamic action—befits plays such as his successful Orphan of Zhao (2015), here the zany stories don’t sit well with the music. In some scenes, music had to take the back seat.

Shining ‘Idols’ of the Changgeuk World

Ko’s cast was abound with playful energy; the young pansori singer-actors were always moving onstage. This production relied much more on movement than acting via song. The old prejudice that changgeuk performers hate movement is clearly no longer valid, as the cast seemed eager to be on their feet even if it was exhausting. Yoon Choong-il, an honorary member of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea, made a rare special appearance, uniting Heungbo and Jung in marriage by performing his specialty, the Poomba Taryong. Yoon’s stage presence was especially notable because the Company has grown quite young in recent years. Even though the performers have honed their skills for over twenty years, many of them are only around thirty because they started training at such an early age. While the Company’s female members dazzled audiences in The Trojan Women (2016), Heungbo-ssi showcased young male performers among a balanced mix of new and seasoned singers, including Kim Joon-soo and Choi Ho-sung in the roles of Heungbo and Nolbo, Choi Yong-suk as Madangsoe, Yoo Taepyongyang as the swallow, and Lee Kwang-bok as the government official. These singers are well past their teens, but they are as popular as K-Pop idols in the changgeuk world.

Aside from the relaxed performances of the two brothers, Yoo’s performance of the swallow was a joy to watch. Casting off his rigidness in Orpheus (2016), Yoo was on fire, thoroughly enjoying himself onstage through his movement and singing. Choi Yong-suk, who played an accomplished Dongkyung in Beauty and the Beast (2017), portrayed the clever Madangsoe, enlivening the production with his zest while assisting Heungbo and exposing Nolbo’s ill deeds. Among the female singers, Cho Yoo-a’s alien monk was notable. Ambiguous in gender, I eagerly awaited Cho’s bouncy dance and song as she entreats Heungbo to “empty himself” when I attended the show a second time. It was also delightful to behold seasoned performers playing young Heungbo’s adopted children. Although the supporting roles didn’t have much of a chance to show off their singing prowess, it was meaningful to read these actors as the poor and alienated in our society.

Heungbo-ssi, written and directed by Ko Sun-woong. Photo courtesy of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea.

The Limits of Serious Clowning

Heungbo-ssi’s moral of relinquishing material desires directly confronts the original tale, in which Heungbo is richly rewarded for his kindness. In this case, Heungbo’s reward is transcendence from materialism. As I’ve already mentioned, this can be a meaningful theme in itself. However, the production relies too much on plot to express this idea, at times clashing with the equally overdeveloped music. More problematic, the music sometimes took a back seat to the story.

Ko’s imaginative take on changgeuk certainly brings fresh perspectives to the genre. However, his work does not capture what makes changgeuk unique. His intricate storytelling has limits when it meets changgeuk’s musical form. The audience laughed frequently at the wacky situations and actions, but this laughter didn’t resonate with the musical drama. Rather than access the profundity lying beneath the freewheeling plot, I began to doubt the leaps and bounds from the source material. Perhaps I am reserving my final take on a piece that walks the line between satire and seriousness, merely enjoying the actors’ great performances in the meantime.

Ko’s work often emanates deep love for humanity. But while this feeling hit home in plays such as The Orphan of Zhao, bringing laughter and tears, “serious clowning” met its limits in the changgeuk Heungbo-ssi.

Heungbo-ssi, written and directed by Ko Sun-woong. Photo courtesy of the National Changgeuk Company of Korea.

[1] Kim Hyang, “Research on the Dramaturgy of the Complete Changgeuk Adaptations by Director Heo Kyu,” The Research of the Performance Art and Culture, Society of Korean Performance Art and Culture (2017), 101.

Kim Hyang is a theatre critic and assistant professor at Paideia College, Sungkyul University and research fellow at the Research Institute for Performing Arts in Yonsei University. Her research interests include the practice of playwriting and performance, theorizing changgeuk, and humanist-oriented research of cultural content.

Translated and edited by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

This article was originally published in Korean Theatre Journal, the official journal of the International Association of Theatre Critics – Korea. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kim Hyang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.