The economic crisis in Iceland was messy, merciless and brought an entire nation completely convinced of its own excellence to its knees. Since that fateful fall of 2008, the country’s supposed recovery has been hailed internationally as a global success story. Iceland was the nation that rebuilt itself after an economic catastrophe, where the bankers responsible were jailed, MPs got their comeuppance in the following elections, and its citizens learned a valuable lesson in humility. Untrue. All of it.

A week before the Icelandic general election, the second one in a year after the last two governments imploded, God Bless Iceland by director Thorleifur Orn Arnarsson and writer Mikael Torfason opened at Reykjavik City Theatre. God Bless Iceland is based on an investigative report compiled by the Special Investigation Commission, published in 2010, analyzing the process leading to the collapse of the three main banks in Iceland during the autumn of 2008. The report, commissioned by Althingi (the Icelandic Parliament), is massive, spanning nine sections and a little over two thousand pages. When originally published the Reykjavik City Theatre staged a reading of the report, which was also live-streamed and took 145 hours of continuous reading to complete. The title of the performance is based on an infamous televised speech by then Prime Minister urging for calm and caution during the crash ending with the words: “God bless Iceland.” It became the stuff of legend, a speech so out of touch with reality ending with a desperate call for a higher power to bless the country when the responsibility lay with the people in power.

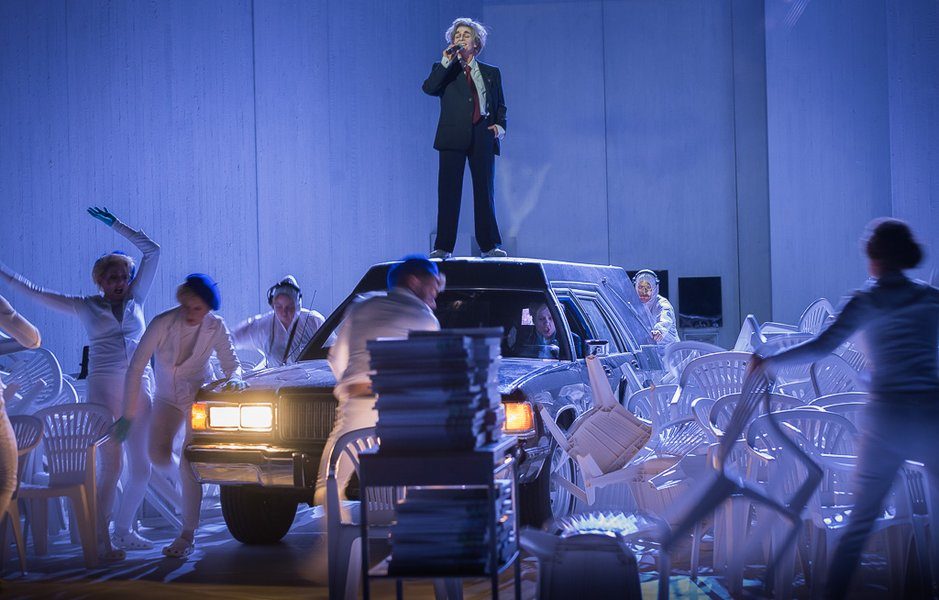

Guð blessi Ísland. David Oddson enters the stage riding a hearse driven by Hannes Holmsteinn Gissurason. Press photo

Last spring Thorleifur Orn premiered The Elf Palace at the National Theatre. The production’s central premise was questioning the place and purpose of theatre in modern society. Here the same premise is explored but the makers reach further back into theatrical history and the stage is presented as a ceremonial altar of sorts where the cast, the characters they play and the audience can cleanse themselves. This is a communal ritual. However, the stage is not a place of answers but of questions, a journey into the heart of darkness and denial. Concepts that Icelandic people are very familiar with as the days grow shorter.

The creators called the piece “a rock opera” in interviews before the premiere but it is rather more like a post-modern and post-dramatic cabaret throwing together thirteen songs from extremely different directions. The show is hosted by two MCs whose approach to the project differs vastly; one presumes the glass is half-full while the other believes it’s half-empty. This all-singing, all-dancing pandemonium culminates in a performance of Lucky by Radiohead where actress Marianna Clara Luthersdottir inhabits Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, Iceland’s former president, in a stunning attempt at a theatrical mea culpa.

Marianna Clara is not the only woman here inhabiting a male role as there are two other men, played by women, desperately trying to usurp the proceedings throughout. David Oddsson, played here by Brynhildur Gudjonsdottir, is a political giant (some say ogre) of Icelandic political history of the past 40 years: Chairman of the conservative Independence Party, former Mayor of Reykjavik, former Prime Minister, Head of The Central Icelandic Bank during the financial crash and currently one of the Editors-in-Chief of Morgunbladid, a conservative newspaper. Here he is aided, as often in real life, by the infamous conservative Professor of Political Science Hannes Holmsteinn Gissurason, played by Kristin Thora Haraldsdottir who boyishly basks in Oddson’s glory. By taking over the roles of these men, women are claiming and taking over the narratives long held by powerful men, rewriting the story they created, guarded over decades and protect to this day.

Post-crash the bankers balked as they felt they had done nothing wrong, they were just misunderstood, they were simply following the law of the market and felt persecuted by the relentless and unfair media. One of the highlights of God Bless Iceland is a self-help lecture held by one of the major contributors to the crash explaining how we should all try to better ourselves. It feels like a cross between a Herbalife pitch, a church service, and an AA meeting. Another highlight is a speech by a well-known wife of a jailed banker who finds her own personal and unhinged salvation on a mountaintop overlooking her husband’s jail.

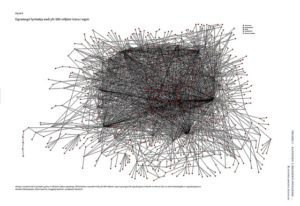

However, the drama is not properly perceived without an understanding of how small the wealthy elite is in Iceland. One of the most brutal images of the report was the graph showing the asset connection of companies worth more than 500 million Icelandic kroners (5 million US dollars in today’s currency). The elite is never connected simply by money or business dealings but also through personal relationships, whether it be by family or friendship. And nowhere is this more obvious than in a country with a population of 320,000.

Image from the report showing the asset connections in Iceland.

The performers constantly break the fourth wall expressing how difficult it is simply to wrap one’s mind around the enormity of the crash, the complicity of many and question whether they were somehow also responsible. They are regularly exposed, both figuratively and literally, to the harsh impossibility of their quest, unable to progress with the performance without breaking character. The weight and complexity of history seem simply too much to bear and understand, let alone explain in a linear manner, or in any manner at all. In the end, we are all hypocrites. Everyone has to take responsibility for their actions and their part in society.

There is a force attached to most of Thorleifur’s work, sometimes a little too unbridled and chaotic, but in God Bless Iceland he manages to tame his urgency, funneling it toward a clear goal. That is not to say that the performance is not chaotic, it most certainly is. He also has a tendency to underline his message, feeling the annoying need to explain every minute metaphor, but finds a different approach this time. Clocking in at three hours the performance never feels overlong but rather like an extended, body-shaking exorcism. Ultimately, the tragedy is that nothing has fundamentally changed. Sure companies and stocks have changed hands and elections have happened but the Icelandic people seem to be physically and psychologically incapable to figure out how to rid itself of the festering rot at the core of the nation.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sigríður Jónsdóttir.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.