“Medicine is my lawful wife and literature is my mistress,” said Anton Chekhov (1860-1904), “when I get tired of one, I go to the other.”

Chekhov’s words, I suppose, make sense to East Africans, because even here, generally, one is expected to pursue a “serious” profession whereas art is seen as something that one does “on the side.” The Russia that Chekhov lived in is very similar to our time in this sense.

Chekhov was born just a year before serfdom was abolished in Russia. Chekhov’s grandfather himself was a serf and had managed to buy his family’s freedom in 1840. It was, therefore, a time of a diminishing aristocracy and a rising a middle-class–a middle-class growing in wealth but lacking in the taste and refinement that art cultivates.

Lopakhin (also called Yermolay), one of the central characters in his 1903 play, The Cherry Orchard, typifies this sprouting middle-class. He is a successful merchant–what we would now call (in Kenya) a hustler–and has known, since his childhood, the aristocratic family of Lyubov Andreyevna, whose estate is about to be auctioned to offset the mortgage.

Lopakhin tries to help them save their estate by suggesting that they divide the land into little parcels and lease these to developers in the emerging tourism industry. This will involve cutting down the cherry orchard, which constitutes a large part of the estate.

For Lyubov and her brother Gayev, the orchard holds fond childhood memories and Lopakhin’s suggestion–sensible and unavoidable as it is–essentially means, for them, cutting down art, heritage and culture, to make room for commerce.

Seemingly in denial of the fate that awaits them, Lyubov and Gayev do absolutely nothing about the situation. In fact, they throw a lavish party on the eve of the day of the auction. Lopakhin buys the estate and cuts down the cherry orchard.

“If only my father and grandfather would rise from their graves and see what has come to pass,” he says in Act III, “see their beaten, barely literate Yermolay buy the estate, the fairest thing on earth.”

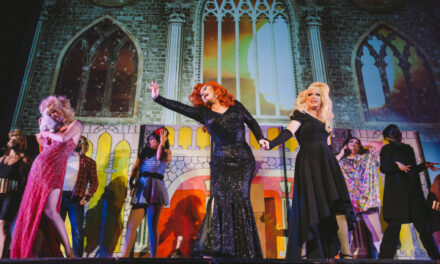

Photo credit: Li Bing, courtesy of company

The old social order is fading away, inevitably giving way to the up-and-coming bourgeoisie, but at what price? This is what Chekhov seems to be asking here, but like all his plays, he offers no solution.

This question of the changing social order is what was going through my mind as I watched a production of The Cherry Orchard by the Russian director, Vladmir Petrov at the Dong Cheng campus of the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing, on October 19, 2014.

The play was one of four theatre productions that I watched during the 27th World Congress of the International Association of Theatre Critics, where critics from 29 countries convened to discuss the whereto of theatre criticism in the internet era.

Performed in Chinese, with no subtitles (although most critics know the play, some even by heart, in their respective languages) it was by far the most memorable of all the productions I watched while I was there.

Petrov went for a minimalist set–a bare stage with a long, light, white cloth draped along the entire height of the stage, turning horizontally or vertically across the stage and varying in width, depending on the scene. This, and the use of a dozen or so full sacks, created the scenes in both indoor and outdoor spaces.

In the scene where Lopakhin buys the estate and orders the orchard to be cut down, he takes a knife and tears open the sacks and little balls, wrapped in red crepe paper, so that they look like cherries, pour out of the sacks and cover the whole stage in a beautiful picture of affluence and extravagance.

I wonder what this play means to the Chinese audience–in a China at the threshold of economic dominance. Is there a sense of having cut down their cherry orchard to give way to economic development?

Three days earlier–October 16–we were regaled by a performance of the traditional Peking opera. Then, the following night, in a little experimental theatre called Peng Hao, that could just about sit all 80 critics, some students had the rare and unenviable occasion of performing a physical theatre production Sound And Breath, to a house full of jet-lagged critics. Not the best production by a stretch, but it did prove that modern trends ran alongside the traditional, in Chinese theatre.

Then on October 18, we watched, at the breathtaking, state-of-the-art National Centre of Performing Arts, Donizetti’s comic opera Don Pasquale. The Italian director Pier Francesco set it in the 1940s with a rather Churchill-like Don Pasquale (Bruno Praticò) and a most remarkable Ernesto (Shi Yijie).

My overall sense of the whole experience is that China is very keen to build her cultural capital. In fact, I would say, China is keen to re-plant her cherry orchard.

This review first appeared in The East African 29th November-5th December 2014, under the title Anton Chekhov’s ‘Cherry Orchard’ Blossoms In China

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anne Manyara.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.