Youth Theatre, Novi Sad. Premiered February 27, 2022.

A few days ago, a friend who is a teacher told me a story of her high school student who beat his fellow female classmate, hitting her with fists so strongly that other peers barely managed to separate him from her. The supposed reason for his aggression – she sat on his chair. A few days before that incident, my mother told me that in our hometown seven young men beat up the son of her customer, so hard that his skull was broken and he has a one percent chance of survival. Not long before, I heard a story from the same town of a barely adult man who beat and tried to rape his girlfriend, but luckily she escaped and he is now spending time in prison – a rare sexual assault case that resulted in a legal penalty.

I could go on naming these acts of violence almost endlessly, as I’m sure many of us can. And we didn’t even touch the subject of mass school shootings in the West, nor the institutional violence perpetrated by states around the world. In this context, examining the issue of violence in contemporary theatre is not only desirable, but necessary. Perhaps that is the reason why Youth Theatre from Novi Sad invited the renowned director Kokan Mladenović to stage Children of A Clockwork Orange together with 10 young aspiring actors.

The text for the show, written by Mladenović and the dramaturge Nina Plavanjac, is inspired by Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange, a dystopia with a terrifying young adult anti-hero Alex who leads a gang that relishes ultra-violence – including sadism, rape, and murder.

Although the show isn’t an outright dramatization of the novel, it is quite faithful to it in major plot points and themes of exploration. The show is, like the novel, broken into three parts – the first, where Alex and his gang commit hideous crimes; the second, where he ends up in jail and participates in a negative behavioral conditioning program, so he could be only nauseated by the thought of violence; and the third part where he comes back to the free world as “cured,” but undergoes violence himself since he encounters his vengeful victims.

Three different actors play Alex in these three different stages of his story – Darko Radojević, Miloš Macura, and Aleksandar Milković, respectively. All of them convincingly play the anti-hero as calculated, manipulative, and perversely charismatic, with a violent essence underneath that doesn’t burst randomly, but manifests in a monstrous and bizarrely artistic way, quite like choreography to the tunes of his favorite “Ludvig van.” Aleksandar Milković especially adds complexity to the character since he plays him at a moment when he is released from prison and finds himself abandoned by everyone once close to him, including his parents.

Milković’s portrait is full of contradictory feelings of anger, betrayal, despair, and,

yes, for a second it might also be love, which testifies that Alex is not only a psychopath, but a product of the society that failed him.

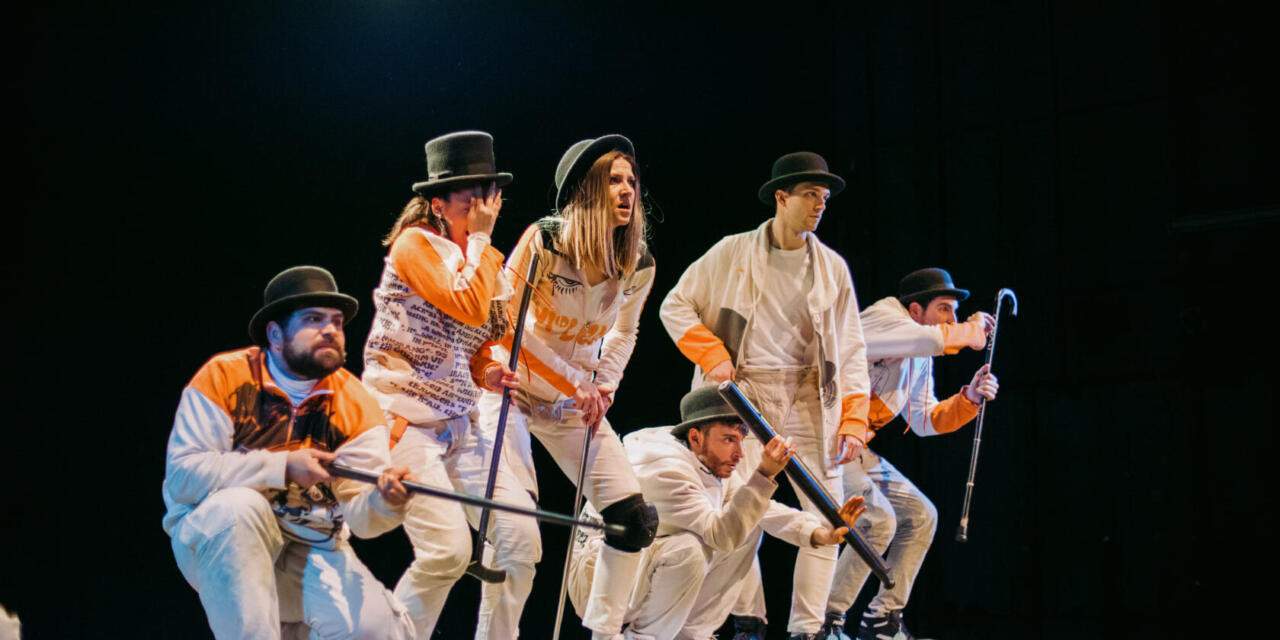

Children of “A Clockwork Orange” at Youth Theatre Novi Sad.

The show also doesn’t ignore Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film adaptation which revitalized the novel’s popularity. The costume (Marina Sremac) is a homage to the film since all of the gang members are dressed in stylized white and creepy outfits with details in orange and black or orange cylinder hats. But this image is also “updated” to suit the contemporary moment where another pop-cultural character is a symbol of ultra-violence, and destruction, but also of the oppressed – the Joker. Gang members often commit rape, murders, and other crimes while wearing a joker mask.

But the mere representation and reproduction of violence would be quite regressive. Burgess’ novel actually isn’t about violence at its core, it’s about the question of free will. Deeply impacted by Catholic thought, Burgess raises the question of whether a person is still human if their free will is removed, even if that means that they can only be good and cannot choose evil and violence.

Children of A Clockwork Orange also deal with this subject, but it is not central to the show in the way it is to the novel. Mladenović and Plavanjac explore how can this story be relevant in this concrete moment in Serbia, but also in other societies in the region. Know as a fierce critic of the governments and the political mainstream in the region, Mladenović also doesn’t shy away from direct although appropriate political commentary in this show too. Alex’s gang can be seen as violent nationalistic hooligans that we know so well from reality. But they are, at least at the beginning, not loyal to any particular political group, they sing patriotic songs about the city because they are the lords of the streets.

The show’s ending points most directly to the social critique – our anti-hero becomes the vice-president of the corrupt ruling party, because his behavioral conditioning program proved controversial, and since the minister (Aleksa Ilić) is determined not to lose the elections, he elevates Alex from a victim to a high-rank politician. A former gang leader that terrorized the streets joins forces with the personalization of institutional violence. And that is a convenient ending since it’s repeatedly pointed out through the show that Alex is a product of institutions that are at best in disarray and at worst openly violent – schools, family, social services, police, judiciary, government… The list goes on.

Perhaps the biggest quality of Children of A Clockwork Orange is that it can simultaneously familiarize Youth Theatre’s young audience (15+) with a version of Burgess’ classic story and offer uncompromising social critique suitable to our current political condition where violence is brought down successively from the top of society to the bottom.

Credits:

Authors: Kokan Mladenović, Nina Plavanjac

Director: Kokan Mladenović

Dramaturg: Nina Plavanjac

Assistant director: Igor Pavlović

Scenography: Marija Kalabić

Costume: Marina Sremac

Assistant costume: Sava Stefanović

Composer: Marko Grubić

Sound: Filip Gotovac

Lighting: Ratko Jerković

Cast: Darko Radojević, Miloš Macura, Aleksandar Milković, Aleksa Ilić, Anica Petrović, Danilo Milovanović, Kristina Savkov, Nenad J. Popović, Nikolina Vujević, Stefan Ostojić

This article was originally posted to SEEstage.org on March 2, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Borisav Matić.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.