There are plays that feel timeless because they strike familiar chords and speak to something at the heart of our nature as human beings, which might make us feel nostalgic for lost youth, happy to find ourselves in civilized times or saddened by the tragic choices people have been moved to make time and again…and then there are plays that are both timeless and timely and The Resistible Rise Of Arturo Ui is the best possible choice The City Garage could have made of the lot of them.

Set in Chicago in the 1930’s, written by Bertolt Brecht in 1941, the play was not produced until 1958 in West Germany followed by two English adaptations for Broadway – neither of which ran for long [by any internet search account, there seemed to have been a total of 18 performances between the two]. Jennifer Wise undertook an adaptation of the play in 2002 with a focus on the Warner Bros. style of Gangster film banter that inspired Brecht to begin with, and we should thank her.

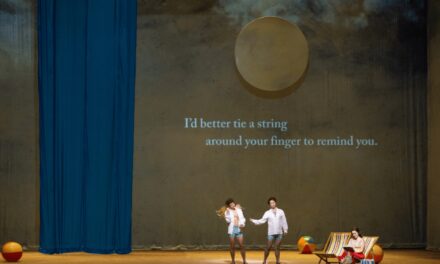

Angela Beyer [Dockdaisy], Andrew Loviska [Arturo Ui]; (background: Gifford Irvine [Ernesto Roma]) in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui Photo by: Paul M. Rubenstein

The City Garage makes good use of Wise’s rapid-fire and engaging translation with a cast that embodies all things 1930-40s Gangster with strong physical choices and a bevy of accents that are impressive and delightful. In particular, cast members Angela Beyer [Emcee / Dockdaisy / Maid / Singer / Flower Girl / Inna] and Beau Smith [Buther / Greenwool / Doctor / Dullfeet / Gunman / Grocer] seem right at home on this stage in this style. Beyer has at least one scene-stealing moment as a Maid to Troy Dunn’s beleaguered Dogsborough that had the audience chuckling.

Gender neutral casting choices allows us to enjoy watching Geraldine Fuentes [Clark / Prosecutor], Lindsay Sawyer [Caruther / Singer / Hook / Woman / Flower Girl / Grocer], Sandy Mansson [Flake / Judge / Pastor / Grocer] and Trace Taylor [Sheet / O’Casey / Actor / Gunman / Grocer] play the role of the heavy one minute, the role of the victim the next–and all shades in between before the play is done. Ui’s trio of inner circle thugs played by Gifford Irvine [Ernesto Roma], Michael Cortez [Giuseppe Givola] and Nathaniel Lynch [Emanuele Giri] solidify his position as the man in charge but it is Andrew Loviska’s work as Arturo Ui that keeps the play grounded even when the production honors Brecht by employing alienating tools, like one tap number [Beyer and Sawyer] with vocals sung over a recorded track. Loviska brings a boyish angst to the role that makes him feel more unpredictable and dangerous than we should be comfortable with while also revealing how people-smart the character is.

Left to Right: Angela Beyer, Andrew Loviska, Lindsay Sawyer Photo by: Paul M. Rubenstein

Ui: “I have to face the facts: this is what men are–they ain’t no little lambs… Man will never lay down his gun of his own free will–neither for goodness’ sake, nor to get his praises sung by the choirboys at City Hall. Because if I don’t shoot, the other guy will. It’s only logical.”

Ui wants to be respected, but not by the elite–by the “little man” that will make him their master. He uses the elite to get what he wants, and this is best illustrated by Ui’s interactions with Betty Dullfleet [Lindsay Plake], wife of Dullfleet, a leader in neighbouring Cicero. When Ui overtakes the Cauliflower Trust in Chicago, he wants to strengthen his standing by making a deal in Cicero. Things do not go so well for Dullfleet when he resists this and Betty is left with Ui on her own. Vividly enacted by Lindsay Plake [she takes on the roles of Ragg and Defense Counsel during the fire trial as well], Betty endures Ui’s most blatant aggression and is practically crushed before our eyes.

Andrew Loviska [Arturo Ui], Lindsay Plake [Betty Dullfeet]; (background: Michael Cortez [Giuseppe Givola]) Photo by: Paul M. Rubenstein

There is one moment in this scene where Michel and Loviska make the choice to have Ui tuck his private parts back between his legs as he drops his pants that feel unmotivated. He’s showing how far he can push things but the Jesus-like pose struck at that moment will forever call “Silence of the Lambs” to anyone’s mind that has seen that film and it diminishes the power of the interaction between Betty and Ui. The two actors are strong enough to pick up that momentum the moment he’s dressed and back in her space in the fiercest way, but one can’t help imagine what the scene might be like without what feels like this distraction.

Though author Wise states in the forward to her translation that the play works best as a “cautionary tale about the conditions under which fascist brute force can triumph anywhere, even in democracies with proper legal institutions,’ going on to state that the play is less about Nazism and therefore suggests that it works best if the stage is “kept quite clear of swastikas and Hitler mustaches,” director and company Artistic Director Frédérique Michel does not shy away from making clear correlations.

Riffing off the opening lines of the play wherein we are given information about the world and its state via a series of headlines, Michel encourages connections to Nazi Germany by having the newspaper boy and other characters share headlines from newspapers throughout the piece each time there is a correlation between an event in the play and an event that occurred in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power. These historic parallels are listed for us in the program, letting us know that Brecht’s Warehouse Fire Trial mirrors the Reichstag Fire Trial. And this production embraces the Hitler moustache in Ui’s final appearance, dressed in a slick suit, standing before a projection of the Reichsadler [Nazi Imperial Eagle] as he gives a speech that reveals the level of attention to gestural detail that Michel and Loviska have put into this performance.

One might argue that Wise was correct–that by making this so specifically about Hitler, the play loses some of its universality. Ironically, however, given our current political and civil climate in these United States, the direct Nazi references prompt us to think about parallels to our present day that work extremely well. Just watching the trial about the fire can make your hair stand on end as you listen to Plake’s Defense Counsel struggle to give justice the breath of a chance. The Trump Administration is not in this play but the work casts a shadow that looks eerily similar to their own in ways that are important.

This is the best thing the theatre can do for us. Yes, it looks like it is long–just short of three hours when you consider the time for intermission [the bathroom situation at the theatre results in a line that cannot comfortably accommodate ten minutes–one hopes some inspired patron or new city code might be able to alter this one day]–but each of us have spent at least that much time this past year in a movie theater watching the latest Marvel / Star Wars / Action film and the time flies by here in fascination. At intermission I overheard one patron explain that Brecht occupied a house not six blocks away from the theatre’s location when he escaped Germany in 1933. He had something incisive to say then about the conditions in his homeland and what he crafted is just as exciting, unnerving and at its roots terrifying to consider today.

Andrew Loviska, Angela Beyer Photo by: Paul M. Rubenstein

The production makes use of the minimal space dividing it up into four playing spaces–a riser stage left with a posh chair, rug and table indicating a mansion, a riser stage right with brick encrusted windows and wooden crates illustrating the street or the dock or general locations, a riser along the back wall that shifts mood with the use of projections that comment ever so lightly on the action playing out in front of it and the playing space downstage of a drawn curtain that underlines the theatricality of the piece in all necessary ways Brecht. Production, Set and Lighting Design was brought to life by Producing Director Charles Duncombe with Costume Design very well done by Josephine Poinsot, Geraldine Fuentes and Diana Mann. Video Editing by Jaime Arze. Trace Taylor is the Assistant Director and Jerry Winstead is the Literary Manager / Dramaturg.

For more information: Contact Charles Duncombe, Producing Director Charles@citygarage.org.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine Deitner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.