Now in its twelfth year, the Between.Pomiędzy Festival of Literature and Theatre has made much of its international impact with extraordinary special theatrical events like legendary Polish director, Włodzimierz Staniewski, who in May of 2014, led a procession of conference participants along the Long Street of Gdańsk to the brick, Gothic Church of St. John now St John’s Center for a performance of a Pythian Oratorio by his theatrical group, OPT Gardzienice.[1]

On 16 May 2018, Theatr ZAR offered Jarosław Fret’s one-hour-and-five-minute production of Krapp’s Last Tape at Teatr Wybrzeże in Sopot, Poland. The evening began with a lecture by actor Alessandro Curti on how to peel a banana, the fruit distributed to audience members as each entered the theater, in precise, rhythmically choreographed stage gestures.[2] The playing space was defined not by the cavernous Teatr Wybrzeże open space but by a cubicle set off by piles of stacked banana boxes in which space Krapp is confined. Post lecture Curti rummaged through boxes, pulled out some clothing, changed and so transformed himself to become the 69-year old Krapp. The language of the banana lecture was English; the group’s performance language is generally Polish; this performance was in Italian. (For the 2021 festival see the conversation between Fret and Octavian Saiu).

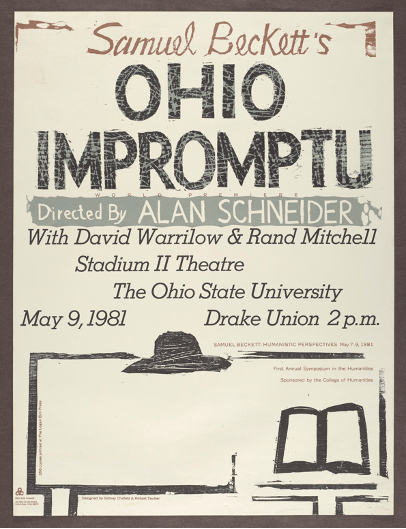

Poster of Ohio Impromptu premiere. Artist: Sidney Chafetz.

Staniewski would follow up his 2014 appearance at the Between Festival during the 2020 theatrical lockdown with a groundbreaking work in progress, a virtual workshop performance of Samuel Beckett’s controversial, prohibited and so professionally unproduced play, Eleutheria, which has now been translated into Polish by prominent translator and Beckett scholar Antoni Libera. But the translation was not without issue as the French publisher refused publication rights unless the publication included French publisher Jerome Lindon’s attack on its American publisher, Barney Rosset, and his declaration, supposedly channeling Beckett, that the play was a total failure.[3] No counter analysis was allowed. One might see such intervention and restrictions as censorship, at least a ham-fisted attempt to control the reception of and future scholarship on the work. The original plan for the Polish translation was to include my 1995 “Introduction” to the American edition which praises the play as a precursor to Waiting for Godot.[4] The counterattack by Libera was to translate my “Introduction” and publish it separately in a highly influential Polish arts quarterly, Kwartalnik Artystyczny [The Artistic Quarterly].[5] For his part, Staniewski would plunge headlong into the Eleutheria project, risking in the process the ravages of the pandemic and the wrath of the Beckett Estate. Such a gesture reminds us that theatre is always and fundamentally about risk: financial, creative, political, psychological. It is a fragile medium with any number of breaking points, and its artists are perpetually vulnerable, of necessity exposing themselves to risk. And Staniewski is returning to this Beckett project in 2021 beginning live workshop performances of Eleutheria as part of the Gardzienice Theatre Academy.

The 2021 Between Festival would continue under lockdown, pandemic conditions and so a major festival feature, its annual Samuel Beckett Seminar, which was the starting point of the Festival in 2010, remains a conference focus. Its annual Beckett Seminar is held in conjunction with the Samuel Beckett Research Group at the University of Gdańsk. In 2021 two sessions of the seminar were offered, Ohio @ 40, a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the premier of Ohio Impromptu that was originally staged for a single performance at the Ohio State University’s Humanistic Perspectives[6] conference (hence the play’s title) celebrating, if that is the word, the completion of Samuel Beckett’s 75th year on the planet. The second Seminar featured a group of experimental, lockdown performances called collectively The Virtual Beckett.

Ohio Impromptu would be described by Tom Stoppard biographer, Hermione Lee, as “a mysterious 12-minute exchange between two characters.” (p. 604). In an endnote to her brief discussion of the play, Lee offers a partial provenance, “The 1981 play was a commission for a Beckett expert at Columbus, Ohio” (referenced to page number 604), not exactly news in 2021, but curiously neither revealing the identity of that “expert”—an omission to suggest added mystery, perhaps—nor suggesting that the “commission” (not a word I would have chosen) was the reason for the geographical reference in the play’s title but repeated nowhere in the play. Admittedly, Lee was drawn to the play not through Beckett himself but because Stoppard was originally commissioned by the Gate Theatre’s Michael Colgan to “adapt” and stage the piece for the 2002 Beckett on Film project that would include film versions of all 19 Beckett stage works. While the Beckett Estate, uncharacteristically allowing the plays to be filmed (it was after all an Irish project), it overruled Stoppard’s decision to set the piece specifically on or near the Isle of Swans in the Seine. The Estate objected to such localization even as the Isle and perhaps Paris are central to the narrative within the play, but Stoppard’s screenplay was rejected. Stoppard saw himself as making a film, after all, as he had with his own Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, and not simply filming a stage play, but evidently the Estate wanted the works restricted to the stage. Such difference between stage play and film informed my own workshop reworking of Beckett’s teleplay, not one of the works filmed in 2002, . . .but the clouds. . . , for the 2018 Between.Pomiędzy Festival (available on YouTube).

The 2021 Samuel Beckett Seminar, chaired by Professor Tomasz Wiśniewski, creator and director of the Beckett Research Group in Gdańsk, included me, Jon McKenna (actor, London), Robson Corrêa de Camargo (Federal University of Goiás, Brazil), Paul S. Shields (Assumption College, Worcester, USA), Octavian Saiu (University of Sibiu, Romania), and Nicholas Johnson (Trinity College Dublin, Ireland). The round-table opened with a discussion of my Keynote lecture, “Beckett’s Dystopian Trilogy, Part I: The Irrelevance of Godot,” that raised the possibility that we may have been asking the wrong questions about Waiting for Godot since its 1953 premiere, suggesting instead that we entertain the possibility of the centrality of Lucky’s speech, his tirade too often dismissed as “incoherent.” As recently as 7 May 2021, discussing a star-studded, virtual production of Waiting for Godot, New York Times theater critic, Jesse Green, argued in general that the New York production lacked comedy, calling it a “lugubrious film.”[7] He further declared “Lucky’s impossible speech — nine minutes of gibberish.” One might have expected a bit more knowledge, more intelligence, really, from a New York Times theater critic than such repetition of High School clichés about the play that he, in fact, earlier castigated with a snarky comment that our attitudes about the play have been shaped by “Decades of high school lit seminars” that transformed Godot “from an enigmatic museum piece into an existential tchotchke.” Green is clearly not a Beckett guy—in knowledge or taste. My keynote address, then, offered a counter position and focused on Beckett’s revisions to the English translation of Lucky’s screed as he sharpened what was a clear thematic thread, a dystopian theme that runs through three of his longer theatrical works, including Endgame and Happy Days, hence the “Dystopian Trilogy” of the lecture’s title. Much of the energy of Godot is generated by the censoring of that cut-up, dystopian thread as Lucky is silenced in Act I and permanently muted (cause unknown) in Act II.

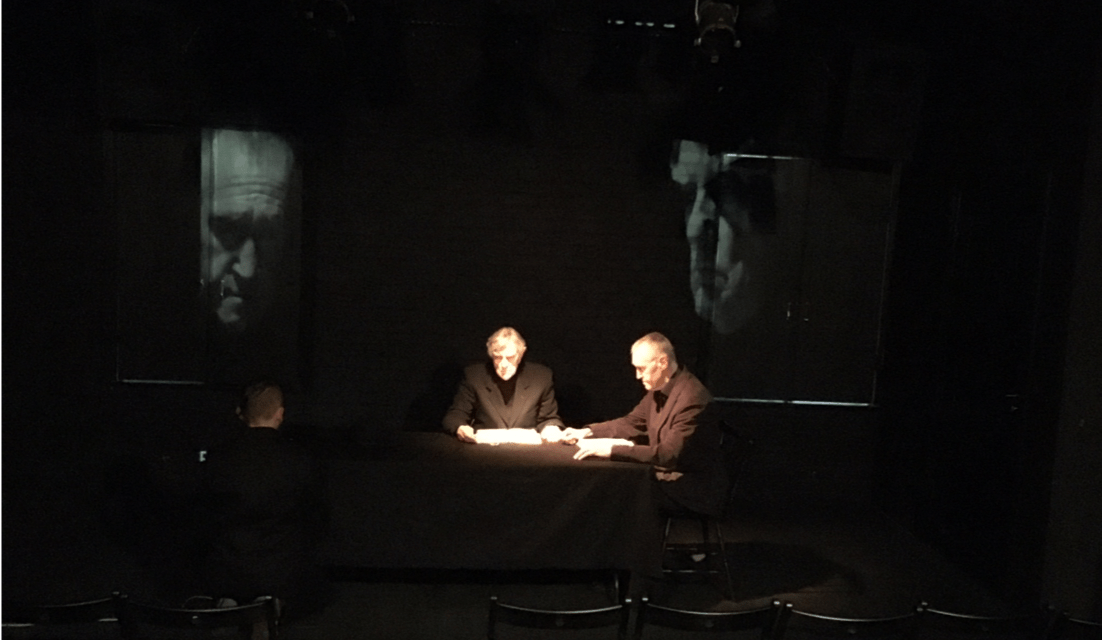

Thereafter, the seminar focus shifted to performances of Ohio Impromptu with a round-table that involved Gontarski, who has been centrally involved with Ohio Impromptu for 40 years, Jon McKenna (actor, London), Robson Corrêa de Camargo (Federal University of Goiás, Brazil), Paul S. Shields (Assumption College, Worcester, USA), Octavian Saiu (University of Sibiu, Romania), and Nicholas Johnson (Trinity College Dublin, Ireland). Four performances of the play were and remain posted to the Gdańsk Beckett Seminar web page and each offered a distinctly different approach to the play. Gontarski staged a very traditional version of the play as part of an evening of Beckett one-acters called “Visions and Revisions: Samuel Beckett’s Theater for Stage and Television,” at the Magic Theater in San Francisco, CA, 25–26 February 1989, which production is available on YouTube and is posted to the Between Beckett Seminar site. Gontarski’s second staging of the play was a bilingual workshop version with Jon McKenna and the late Ryszard Ronczewski that featured not singularities but multiplicities, with projected images provided by Polish visual artist, Elvin Flamingo; that is, the play offered not a single material entity, a person, say, and some sort of apparition or image in an otherwise empty room, but, instead, offered a room full of apparitions, ghosts, memories and other manifestations of the narrated tale; the relationship between the images on stage and those narrated are thereby askew, mismatched, asymmetrical.

My position, call it a thesis, if you will, during the round-table discussion of the play was that much needed to be done to offset if not to counteract the most dominant production of the play, not the world premiere of 40 years ago but the 2002 Beckett on Film version directed by British screenwriter, Charles Sturridge, who replaced Stoppard as adapter and director, and who altered the play in his own way by having Jeremy Irons play both roles, deftly handled technically but thematically reductive. Sturridge’s “adaptation” was apparently acceptable because it remained on a stage.[8] Beckett’s stage directions tell us, however, that the two visible figures (and others are alluded to and so they fill the room) are “as alike in appearance as possible.” To translate Beckett’s stage direction to mean “identical” is a serious rewriting and misreading of the play since much of the dramatic tension of the piece is driven not by similarity but by slippage, that is, difference, the difference between the narrated tale and the enactment we view on stage (or film), the difference between phantom or apparition and material presence, or more generally between presence and absence, between, finally, Reader and Listener. To show both figures as the same character erases such difference and reduces the drama to a standard interior monologue, which Beckett outgrew when he distanced himself from Joyce. Sturridge’s is a production that “explains” the play rather than one that deepens its mysteries.

Other productions were featured during the Ohio @ 40 seminar with round-table participants. Paul Shields’ May Nein (as in the production date of the world premiere, May 9) is a personal reflection on his intersections with Ohio Impromptu (and Hitchcock’s Psycho), using, in part, some of my correspondence with Beckett about the play. Prof. Corrêa de Camargo’s Portuguese production features masked performers in keeping with the name of his theater group, Máskara, celebrating its own 25th anniversary. Even for non-Portuguese speakers its stunning imagery remains a powerful visual experience. Likewise for the elegantly painterly production of the play by Brazilian visual artists Adriano and Fernando Guimarães, exhibiting under the name, Coletivo Irmaos Guimarães.[9] Rather than a comprehensive anthology of possible stagings, these show something of the range of a play that at first may seem static and so undramatic, and they remind us once again of the centrality of performance to the Between.Pomiędzy Festival of Literature and Theater.

Notes

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvcPNcmBLQE

[2] See Anita Rákóczy’s excellent review for the Journal of Beckett Studies at: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/jobs.2019.0275.

For background on the group see further: http://www.teatrzar.pl/en/teatr-zar and https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/07/arts/07iht-grotowski.html

[3] See Mel Gussow’s 1995, New York Times summary of the issues: https://www.nytimes.com/1995/06/25/books/waiting-for-eleutheria.html

[4] “Introduction,” Samuel Beckett, Eleutheria, translated by Michael Brodsky (New York: Foxrock Inc., 1995), vii–xxii.

[5] “Eleutheria Samuela Becketta: historia niewydawania” [“Samuel Beckett’s Eleutheria: A History of Non-appearance”]. Kwartalnik Artystyczny [The Artistic Quarterly] Przełożył i zredagował Antoni Libera. April 2021, 89-100. http://kwartalnik.art.pl/

[6] See also the collection of conference papers of that title that includes high-resolution facsimiles of most of the mss. and tss.

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/07/theater/review-waiting-for-godot-ethan-hawke.html

[8] My position here is not to object to adaptation per see since all Beckett performances, my own experiments included, are adaptations to one degree or another, some drastic as the 2012 musical or operatic production of the play, sometimes boldly called a reinvention of Samuel Beckett one-acts, staged initially at and by The Library of Congress on March 7, 2012, directed by Joy Zinomn with the Cygnus Ensemble, and, then expanded with Footfalls and Catastrophe and touring under the title Sounding Beckett: https://www.broadwayworld.com/off-broadway/article/CSC-to-Present-SOUNDING-BECKETT-914-23-20120723 and https://www.playbill.com/article/director-joy-zinoman-and-cygnus-ensemble-reinvent-samuel-beckett-one-acts-with-new-music-starting-sept-14-in-nyc-com-197567.

[9] See my commentary on their work in “Redirecting Beckett”: https://www.coletivoirmaosguimaraes.com/redirecting-beckett

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by S.E. Gontarski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.