Architectural mapping, façade projection, 3D projection videomapping, display surfaces, and architectural Vj set are some of the definitions used for a new artistic format and a new technique that consists in projecting video images on buildings, façades, and other structures in public spaces (but also in theatres and museums) or on nearly any kind of complex surface or 3D object to shatter the viewer’s perception of perspective. The projector allows bending and highlighting of any shape, line or space. It creates astonishing optical illusions–a suggestive play of light that turns a physical object into something else by changing its perceived form. The context is that of so-called “augmented reality.”

The perceptual illusion, in the most successful cases of videomapping, is that of a “liquid architecture” which adheres as a film or mask over the concrete surface. Fragments of surfaces, as if they were Lego bricks, create an optical illusion of great impact for the audience, which no longer distinguishes between the real architecture and the virtual one. Immediately acquired by major international brands for advertising and the launch of new products, the technique also offers a glimpse of possible performative uses, which would allow combining video art, animation, installations, graphic art, light design, choreography and live theatre .

We are facing a new “machine vision” in a theatrical sense: the video mapping projections are based on the same principle as were the “ineffable visions” of the XVI century–that is, painting created on the basis of anamorphosis, forcing to the extreme the linear perspective of the Renaissance. In the works based on the anamorphic technique, reality can only be perceived through a distorting mirror, while the mapping video is nothing more than a mask that deforms/creates a reality that does not exist.

Art history has given us not only the linear perspective, but also other views–the so called “broken perspective,” the concatenation of the plans and multiple points of view that pose the problem of depth in painting–the imaginary level of the third dimension. We could quote the baroque painted architecture (called quadraturismo, the “work of painting” in the words of Vasari with reference to representations of fake architecture in perspectives that “break through” the limits of the real space, tricking the eye; what Omar Calabrese defines as “the spatiality in painting”) and the trompe-l’oeil.

Tracing the history of the theatre, it is impossible to avoid mentioning the techniques of pictorial representation of the space with the background painted in perspective, the illusionistic sets of the XVI and XVII centuries and treatises thereon: from the drawings of Baldassare Peruzzi for Calandria (1514 ) to Scene- type of Serlio (the painted scene: comic, tragic and satirical, 1545), to the theatre section of the work Perspectivae books (1600 ) to the books by Andrea Pozzo (1693 ) and Ferdinando Galli Bibbiena (1711 ), through the Pratica di fabricar scene e machine of Nicola Sabatini (1638 ).

We could analyse the innovative scene used in theatre to create illusion of depth (without AR technique), as in the work by Robert Lepage (the “landscape” in his Andersen project) and Motus (the three panels with video projection inside the actor in L’ospite by Motus).

Also worth mentioning is the application of videomapping as a dramaturgical element in Giorgio Barberio Corsetti, Klaus Obermaier and Robert Lepage (Ring).

We also could speak about some mapping projects financed by EU in Spain (Girona), Lebanon (Byblos) and Egypt (Biblioteka Alexandrina) in the frame of IAM project (International Augmented Med) and created by Konic Theatre, Marko Bolkovic and Bibalex.

***

Lev Manovich observes that the radical cultural change in the era of information society also concerns space and its systems of representation and organization. Space itself becomes a medium, just like other media – audio, video, image and text – now that space can be transmitted, stored and retrieved instantly. It can be compressed, reformatted, converted into a stream, filtered, computerized, planned and managed interactively.[1] Urban screens mediatize public spaces, bringing to open and collective places an element traditionally used in enclosed spaces, as in the case of cinema, television and computers. On one hand, we consume virtual spaces through electronic devices (cell phones, GPS, huge screens) that change the perception of space and time and social relations; on the other hand, we walk in environments dense with screens, which create a new urban landscape. Paul Virilio notes:

Today we are in a world and reality split in two; on the one hand there is the contemporary, real space (i.e. the space in which we are now, inside the perspective of the Renaissance); on the other, there is the virtual space, which is what happens within the interface of the computer or the screen. Both dimensions coexist, just like the bass and treble of the stereophonic or stereoscopic.[2]

The phenomenon of “giantism” has come to characterize the urban scene in recent years: “hypersurfaces,” “interactive media façades” (walls or architecture), either permanent or temporary, designed to accommodate bright and colorful surfaces and large video projections and screens. Enormous projections with images, lights and LED writing are part of the urban landscape, being prominent in the advertising arsenal. Some of the terms of this phenomenon include urban screens, architectural mapping, façade projections, 3D projection mapping, display surfaces, and architectural Vj sets. They belong to the realm of “Augmented Reality,” but according to Lev Manovich, it is more correct to speak about “Augmented Space,” since there is a superposition of electronic elements in a physical space: a relational space in which people could have a new type of dialogue.[3]

A decade after this technique was launched for advertising purposes, the technology is now being used to create live and interactive performances, live painting, laser painting, and videoart, using the big dimensions of architectural surfaces. In “video-mapping” we can link together graphic art, animation, light design, performances, music and also interactive art and public art. The borders of theater change and widen: the environment is no longer the background; it is the focus of the artwork. Based on advanced technology, artists have created augmented reality video works, and stage designs that use video mapping for great realism and huge projections. Video-mapping is a new media art, a media-performative art. Paul Virilio talks of the “Gothic Electronic” in reference to this aspect of contemporary architecture linked to the role of the images:

I think that the revolution of the Gothic era, which was so influential in Europe in every field, corresponds to the new role of the image as a building material. […] The most interesting images are those of windows, as in Gothic art they corresponded to information that is more intangible, that is transmitted by light in extraordinarily refined creations, such as large rosettes.[4]

The aesthetics of the beautiful, of the astonishing, which Andrew Darley in his book Digital Culture defines as the “aesthetic of the surface,”[5] is behind the spectacular artistic forms related to video-mapping in the work of Urban Screen, NuFormer, Macula, Apparati Effimeri, Visualia, AntiVJ, and Obscuradigital.

What we are seeing today is not unlike some historical precedents. Video-mapping projections are based on the same principle as the “ineffabile vision” of the 16th century–those paintings created on the basis of anamorphosis, forcing to the extreme the linear perspective of the Renaissance. In work based on an anamorphic technique, reality can only be perceived through a distorted mirror; video-mapping is nothing other than a mask that deforms a reality that does not exist at all. Art history has given us not only the linear perspective, but also other views like “broken perspective,” a concatenation of levels, the multiple points of view that pose the problem of depth in painting, the imaginary level of the third dimension. The suggestion, the fictional construction of the space, the union of the backcloths and the first floor, and the resulting artificial illusion are the basis of monumental frescos by Vasari, Tiepolo, Veronese and above all, in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, which joins architecture and painting.

Italian painters of the late 15th century such as Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) began painting illusionistic ceiling paintings, generally in fresco: he employed perspective in painting and techniques such as foreshortening in order to give the impression of greater space to the viewer below. This type of trompe-l’œil as specifically applied to ceiling paintings is known as “di sotto in sù” (“from below, upward”). The elements above the viewer are rendered as if viewed from a true vanishing point perspective. Well-known examples are the Camera degli Sposi in Mantua.

We have said that video-mapping is an art of illusion, an art of perception, so we can make a comparison between two different kinds of OCULO.[6] Andrea Mantegna executed a special fresco decoration that involved all the walls and the vaulted ceilings, adapted to the architectural limits, but at the same time breaking through the walls with illusionistic painting, as if the space were expanded far beyond the physical limits of the room. In our own time, the well-known group URBANSCREEN, with its video-mapping entitled 320° licht, created a visual game of shapes and lights that uses the circular surface of Germany’s Gasometer Oberhausen to amaze the viewer with a sense of void and of depth. As Thomas Maldonado reminds us, Western civilization has became a huge producer and consumer of trompe-l’oeil:

Ours has been called a culture of images […]. This definition would be more true if we add that it is a civilization in which a particular type of image–images made by trompe-l’œil — reach a prodigious realism, thanks to the contribution of new technologies […]. Versimilitude is stronger today, thanks to computer graphics, especially when you consider the latest developments in the production of virtual reality.[7]

Harking back to the history of theater and other attempts to create the illusion of three-dimensional space, we find backgrounds painted in perspective: the drawings of Baldassare Peruzzi for “Calandria” (1514), the painted scene-prototype by Serlio (the comic, tragic and satirical scene, 1545), the theoretical books: Perspectivae by Guidubaldo (1600), Andrea Pozzo (1693) and Ferdinando Galli Bibbiena (1711), and above all, La pratica di fabrica machine ne’ teatri by Nicola Sabbatini (1638).

From contemporary theater, we can quote two examples of scenographies created with a simple technique of illusion of three-dimensional space and allowing perfect integration of the body with the stage or device:

-The “digital landscape” used by Robert Lepage and created by stage designer Robert Fillion for Andersen Project (2005): a concave device that includes images in video projections which, thanks to an elevation of the central structure, seemed to have concrete and lively form, and succeeded in interacting with the actor, who was literally immersed in this strange cube built around him;

-The device used by the Italian group Motus for L’Ospite (2003) inspired by Pasolini’s Teorema: it is a monumental scenography looming and crushing the characters, made up of a deep, inclined platform, enclosed on three sides and composed of three screens for video projections. This video triptych produces the illusion of a huge house without the fourth wall.

Video-mapping Projections in Theater

The use of video-mapping in theater not only concerns the sets (the stage, the volumes in which images can be projected) but also objects: actors, costumes and the entire empty space. The group URBANSCREEN has produced various video-mapping experiments in Europe, starting with What’s up? A Virtual Site Specific Theatre, (Enschede, Netherlands, 2010), in which the actors were moving images projected onto a box-like surface that picked up their intimacy, in a surreal atmosphere. Or Jump in! where the façade of the building becomes a sort of “free climbing wall” for actors who jump, climb, and hide among the windows. For the opera Idomeneo, King of Crete (2011) by Mozart, URBANSCREEN used an architecture of lights that adheres to the volumes of the stage on which the singers acted. This white structure is composed of several blocks that resemble the cliffs that allude to the god Neptune, one of the opera’s characters. Projections adhere to the structure, thanks to a software program called Lumentektur, created by URBANSCREEN.

Apparati Effimeri, an Italian technological group, created a dramatic short scene in baroque style, for Orfeo e Euridice (2014), directed by Romeo Castellucci. They used video-mapping to project the “grove of greenery” from which emerges an ethereal female figure. The projected landscape was worthy of a painting by Nicolas Poussin. We are in Arcadia, the scene unfolds and the video projects on the scene moving images and 3D effects, giving the illusion of wind in the leaves, lights on the water, and evening shadows. The “baroque technologic style” of the set generates the amazing sensation one can experience when looking at large frescoes from the past. It is in perfect symbiosis with the myth and the emotions of the drama, which focus on the image–live from a hospital–of a woman in a coma, who represents in the theatrical fiction the contemporary “double” of Euridice.

Robert Lepage used video-mapping in his most ambitious project: the direction of Wagner’s The Ring cycle, with the New York Metropolitan Opera (2014). The protagonist is a huge machine designed for the entire tetralogy, a true work of mechanical engineering, made up of 45 axes that move independently, surging and rotating 360 degrees thanks to a complex hydraulic system that allows a large number of different forms: a dragon, a mountain, or the Valkyries’ horse. On the surface of the individual axes are projected 3D images in video-mapping, showing trees, caves, the waters of the Rhine, or the Walhalla lights.

IAM Project: A European Project for Video-mapping

IAM (International Augmented Med) was an international, cooperative project in which fourteen partners from seven Mediterranean countries worked together to promote the use of Augmented Reality, video-mapping and innovative interactive multimedia techniques, for the enhancement of cultural and natural heritage sites. The partnership was led by the City of Alghero, Italy. Other participating countries were: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Spain, and Tunisia. It was funded by the European Union’s ENPI CBC Med program, and ran from October 2012 to October 2015.

The winners of the major IAM grants were a Croatian project and a French one. Subgrants were managed by the project partner Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia region – Spain, Department of Culture). In October 2014, the Spanish project partners of the IAM project hosted the IAM festival, in Girona under the title “Jornades APP” (App Days). The event consisted of three days of round tables, demonstrations, presentations, video-mappings, mobile apps and more, in various locations in the historical city of Girona.

In Girona, using the regional office of the Catalan Government, the Barcelona-based group Kònic Thtr-Kòniclab proposed Processus, a large-scale architectural projection based on the history of the building. It combined symbolic elements of the building with elements related to its former use as a hospital, including visuals of medicinal plants. This 17th-century building is infused with life, death and spirituality, as expressed in the Processus project.

According to Kònic Thtr-Kòniclab, video-mapping is based on concepts that define and identify structure. The mapping has to co-exist with the dramatic text, the actor’s actions, the choreography and the sound, taking part in the narrative of the piece and contributing to the tension and development of the piece through its visual evolutions. Kòniclab describes video-mapping in theater:

We can understand it as a treated space, or as a dynamic stage set that will convey dynamics, stories, and actions with duration, via its audio-visual evolution. The media co-exist with the actors and/or dancers, and bring to the piece another layer in a horizontal hierarchy with the other elements composing it. We can think of a global work, in which the different disciplines and materials participate in the narration and composition of the work. The audience, from our experience, perceives the piece as a whole and is often surprised by the intimate and somehow magical dialogue established between light-image-sound-object, or architecture and the actors/bodies, who will convey the human scale and the human-fictional proportions. When the projection is interactive, it offers direct participation of the audience in the piece; they coexist with the actors and can then become a part of the fictional world, taking the step from social being to active participant in the piece.[8]

In their view, the following elements should be taken into account when developing a stage play that incorporates this technique:

– The dramaturgy must be focused on the image mapped onto the object–that is, on the augmented object transformed into a hybrid object-image. The visual narrative is driven by this object-image articulation, and not only by the image. Hence, the object should somehow be related to the visual compositions projected onto it.

-The concept of mapping is a “skin” made of visuals and light covering the volumetric object; a dynamic and flexible skin, which will adapt like a dress to the object onto which it is projected.

-The use of a technology for a totalizing or synthesizing effect: video-mapping must build a perceptual device composed of light, image, sound, software, hardware, space and time, architecture, actors and audience, and all these elements must together create an experiential and relational whole.

Figure 2. Torrei dei Sogni (2015), Koniclab, photography: Rosa Sánchez / Alain Baumann.

Marko Bolkovic and Group Visualia

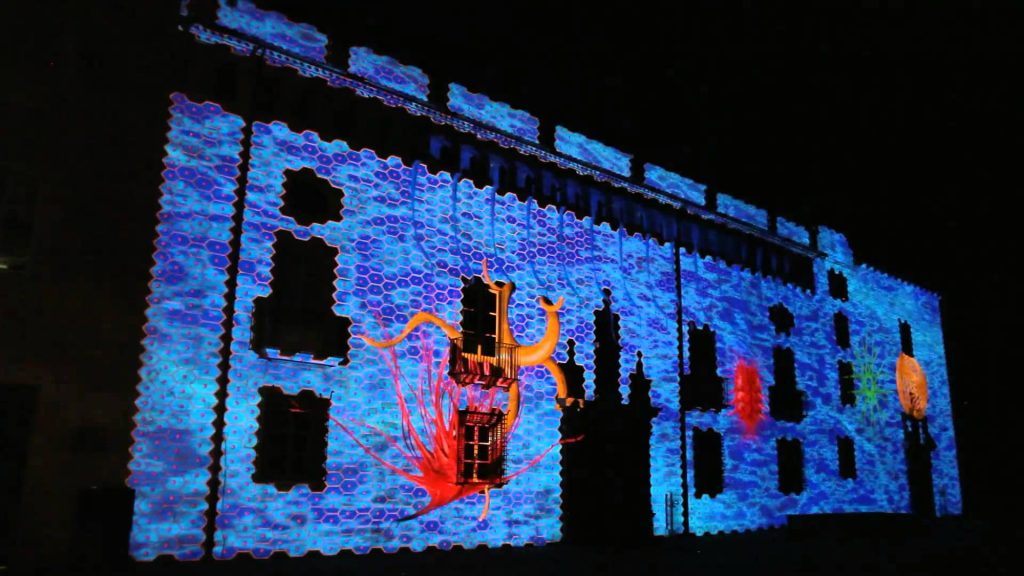

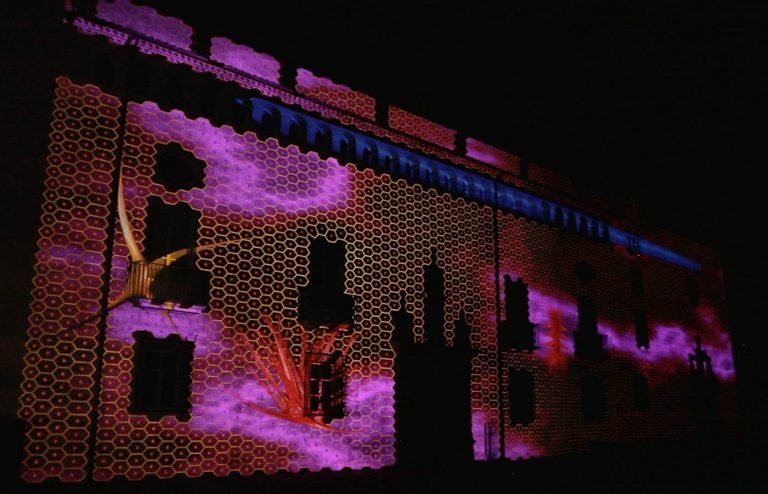

The Croation Group Visualia, one of the two winners of IAM subgrants, presented in Girona Transiency, a mapping made entirely in 3D and inspired by the metamorphosis of life. It was projected onto the historic building, Casa del Pastors. Artistic Director Marko Bolkovic describes the difference between plain video-mapping and 3D video-mapping:

Video mapping can be made with any available material, such as video material, or film. It’s necessary to adjust this material to a projected surface, which is done with special computer software. 3D video mapping is much more complicated and takes more time for its production: first of all, a model of the object where a projection will be made should be created; afterwards all the animation should be made by a special software provided just for that. The greatest difference between video mapping and a 3D video mapping lies in the final outcome – with 3D video mapping you get a realistic space effect on an even surface, and with usual, “ordinary” mapping there’s no such depth and realism.[9]

Figure 3. Transiency (2014), photography: Marko Bolkovic.

Figure 4. Transiency (2014), photography: Marko Bolkovic.

Figure 5. Transiency (2014), photography: Marko Bolkovic.

The group wants to educate people about this rather “new art”– to show its potential and to present its great effect as realistically as possible. In this particular project the artists tried to tell a story about the transiency of things, people, and life itself, combining it with almost magical building transformations, simultaneously realistic and dream-like. The first idea was to create video-mapping with an historical basis – the group wanted to show how the building was built and how it survived for three centuries. Unfortunately, due to a lack of material and information, this approach was dropped. The group then decided to follow its artistic spirit and simply to bring life to Casa del Pastors using a 3D software. Due to the group’s rich experience in 3D video-mapping, they decided that the best way to create a really powerful and realistic effect for the audience was to draw the whole building from the beginning. The front of the building (façade) was challenging enough: it is made out of bricks so it was really one great creative challenge for the group to model and revive the building. The group also agreed that Casa del Pastors is a great place to “tell the story” about the transiency of time, things and life. Everything passes and is unreachable and unstoppable. It exists only in moments, which we are aware of only when they are already gone. “Transiency” became the name of the group’s “story,” which had to be told. How to present transiency through images and video animations? After discussing this, the group decided to start with the creation process – clouds (air element) symbolize imagination from which emerges the water element (life), which continues to a birth process (the tree), and culminates with a simpler form of life (the caterpillar) becoming a higher, more complex form (the butterfly) which is a symbol of free art. The 3D animation was made by Jean, and he divided this animation process in four different parts:

-Geometry – fragmentation and deconstruction;

-Contrast – black and white matter with optical and hypnotic illusions;

-Creation process – air, water, LIFE;

-Colors – free art.

Conclusion

After a decade, the video-mapping technique, born for commercial and advertising purposes, has become flexible enough to create live and interactive performances, live paintings, laser paintings, and video art using the large dimensions of architectural surfaces. In video-mapping we can unite graphic art, animation, light design, performances, music, interactive art and public art. Certain artists use architectural video-mapping in a purely linear fashion, displaying effects produced upon the image and structure of the façade. This approach tends to deplete the poetry of the intervention, by playing with an aesthetic model based on visual and sound effects that the public recognizes and expects. But as we have seen in the works by Kònic and Marko Bolkovic, the architectural mapping has to understand the function of the building in question not only as a façade, but also in its historical context. The artists must bear in mind that they are working with heritage buildings or historical sites. Can technologies enrich and enhance local heritage, contributing a new way of communicating history? Can they offer new and unexpected ways to visit historical monuments and archaeological sites, inspiring a new interplay between traditions and history, between visual and youth culture? We try to reflect on the rules of temporary or permanent media architecture, on their importance for the continued revitalization of the area, on the new role of media for public spaces. We point out the shift in the application of these technologies from commercial, advertising purposes to cultural purposes.

A strategy for sustainable urban media development is imperative, encompassing the needs of residents, tourists, government agencies, commerce, orchestrated by architects and urban planners. We need to reflect on the relationship between the transformation of our cities and the identity-conferring power of digital architecture. A building’s façade is more than just a wall and a framework for the entrance; it reflects the function of the building, and has symbolic patterns, signs or architectural elements that confer character.

If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then with innovative digital media attuned to the place and the audience, we can revitalize public spaces, making visible prior history and functions. Media façades should represent the identity of the building and of the city, with overlapping stories connecting history, emotions, and humanity.

Referring Italo Calvino’s 1972 book Invisible cities, which suggests a poetic approach to the imaginative potential of cities, urban screens and digital mapping works can make visible the invisible, and allow us to understand, create and experience the city with all its change, story, secret folds and diversity.

Such mapping has to co-exist with the dramatic text, the actor’s actions, the choreography and the sound, taking part in the narrative of the piece and contributing to its tension and development through the visual evolutions. We can understand it as a treated space, or as a dynamic stage set, which will transport stories, and actions through time via its audio-visual evolution. The media co-exists with the actors and/or dancers, and brings another layer to the piece. We can think of a global work, in which the different disciplines and materials participate in the narration and composition of the work.

The audience perceives the piece as a whole, and is often surprised by the intimate and somehow magical dialogue between light-image-sound-object, between architecture and the actors’ bodies, which bring in the human scale.

When the projection is interactive, the audience can participate directly in the piece. They then coexist with the actors and become a part of the fictional world, moving from social being to active participant in the artistic work. There are numerous ways in which the audience can be involved interactively. There is still much to be explored and understood, and the rapid evolution of technology will only increase the opportunities for artistic intervention in public spaces.

Notes:

[1] Manovich, Lev. Il linguaggio dei nuovi media, Olivares, Milano, 2002, p. 311

[2] Virilio, Paul. “Dal media building alla città globale: i nuovi campi d’azione dell’architettura e dell’urbanistica contemporanee”, Crossing, n°1, numero monografico Media Buildings, December 2000, p. 10-11.

[3] “Urban screens” is a term coined by Mirjam Struppek considered a pioneer in the field of urban digital surfaces. In 2005, she curated the first Urban Screens Conference in Amsterdam paving the way for the Urban Screens conferences in Manchester, 2007, and Melbourne, 2008. She wrote the essay “Urban potential of public screens for interaction” about the mediatization of architecture, available at <http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/Vol6_No2_interactive_city_struppek.htm>.

[4] Virilio, Paul. “Dal media building alla città globale: i nuovi campi d’azione dell’architettura e dell’urbanistica contemporanee”, Crossing, n°1, numero monografico Media Buildings, December 2000, p. 6.

[5] Darley, Andrew. Videoculture digitali. Spettacolo e giochi di superficie nei nuovi media, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2006, p. 104.

[6] “An oculus (plural oculi, from Latin oculus, eye) is a circular opening in the centre of a dome or in a wall. Originating in Antiquity, it is a feature of Byzantine and Neoclassical architecture. The oculus was used by the Romans, one of the finest examples being that in the dome of the Pantheon. Open to the weather, it allows rain to enter and fall to the floor, where it is carried away through drains. Though the opening looks small, it actually has a diameter of 27 feet (8.2 m) allowing it to light the building just as the sun lights the earth. The rain also keeps the building cool during the hot summer months.” (from Wikipedia: oculus).

[7] Maldonado, Tomàs. Reale e virtuale, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1992, p. 48.

[8] Monteverdi, Anna Maria. Dramaturgy of Video-mapping. Interview with Koniclab, 2014, Web, 6 May 2015.

[9] Ibid.

Works Cited

Arcagni, Simone. Urban screen e live performance, 2009. Web, 10 May 2015.

Artieri Boccia, Giovanni. “La sostanza materiale dei media. Video culture digitali tra virtuale e performance” in Darley, Andrew, Videoculture digitali. Spettacolo e giochi di superficie nei nuovi media. Milan: Franco Angeli, 2006.

Darley, Andrew. Videoculture digitali. Spettacolo e giochi di superficie nei nuovi media. Milan: Franco Angeli, 2006.

Maldonado, Tomàs. Reale e virtuale. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1992.

Manovich, Lev. Il linguaggio dei nuovi media. Milan: Olivares, 2002.

Monteverdi, Anna Maria. Hypersuperface and Mediafaçade. Urban Screen, 2014. Web, 2 May 2015.

—, Dramaturgy of Video-mapping. Interview with Koniclab, 2014. Web, 6 May 2015.

—, L’Orfeo di Castellucci, Musica celestiale per un angelo in coma vigile, 2014. Web, 8 May 2015.

Struppek, Mirjam. “Urban potential of public screens for interaction” about the mediatization of architecture. <http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/Vol6_No2_interactive_city_struppek.htm>.

Virilio, Paul. “Dal media building alla città globale: i nuovi campi d’azione dell’architettura e dell’urbanistica contemporanee,” Crossing, n°1, Media Buildings, December 2000.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Anna Maria Monteverdi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.