Speaking to humanity across time and space, Archive: This Was the End is an interactive sculpture where a past performance mesmerizes the present day. Created by Mabou Mines artists Mallory Catlett and Keith Skretch in collaboration with sound artist G Lucas Crane, the live audio-visual installation is the apex of Catlett’s adaptation of Anton Chekov’s Uncle Vanya.

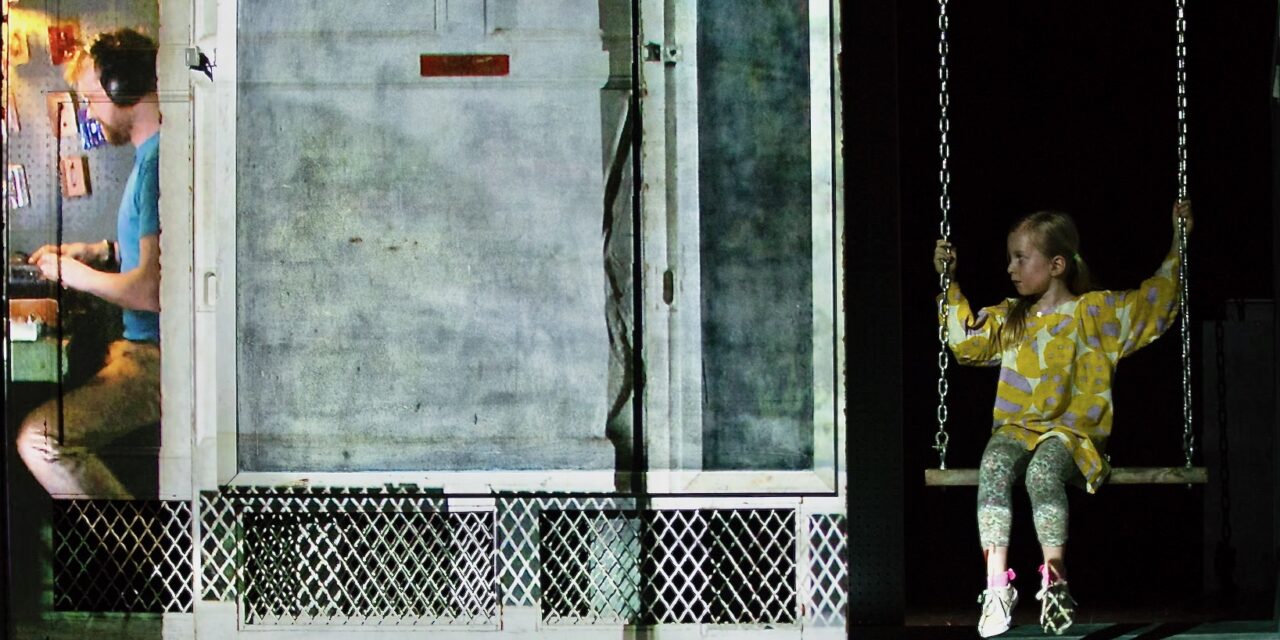

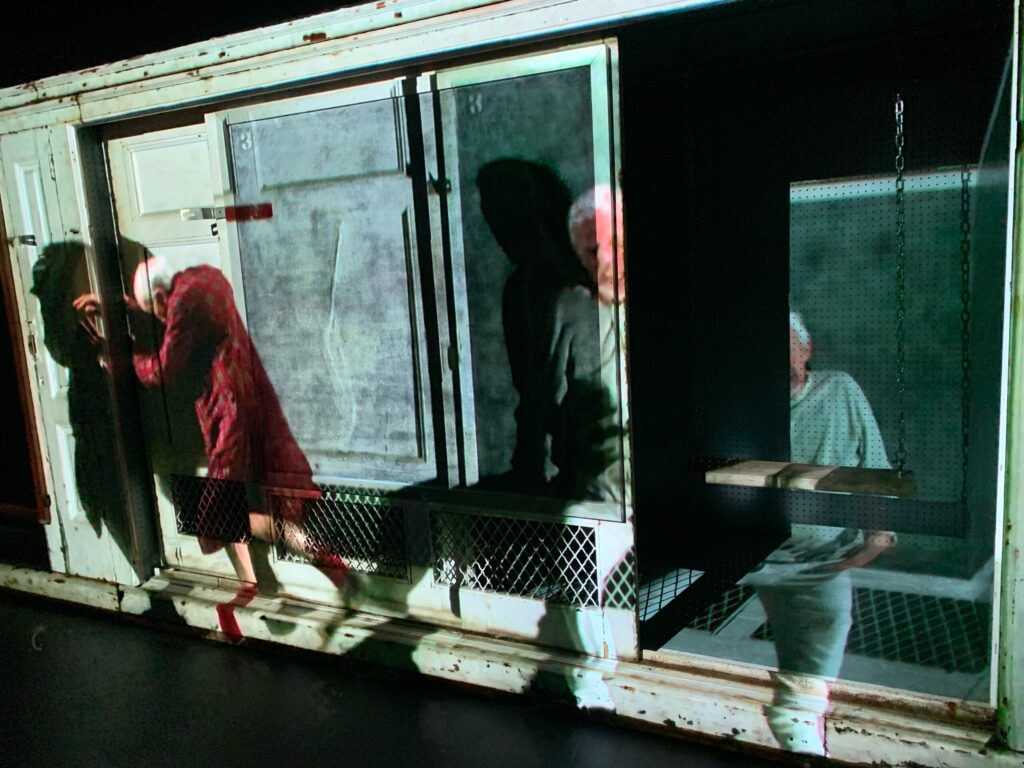

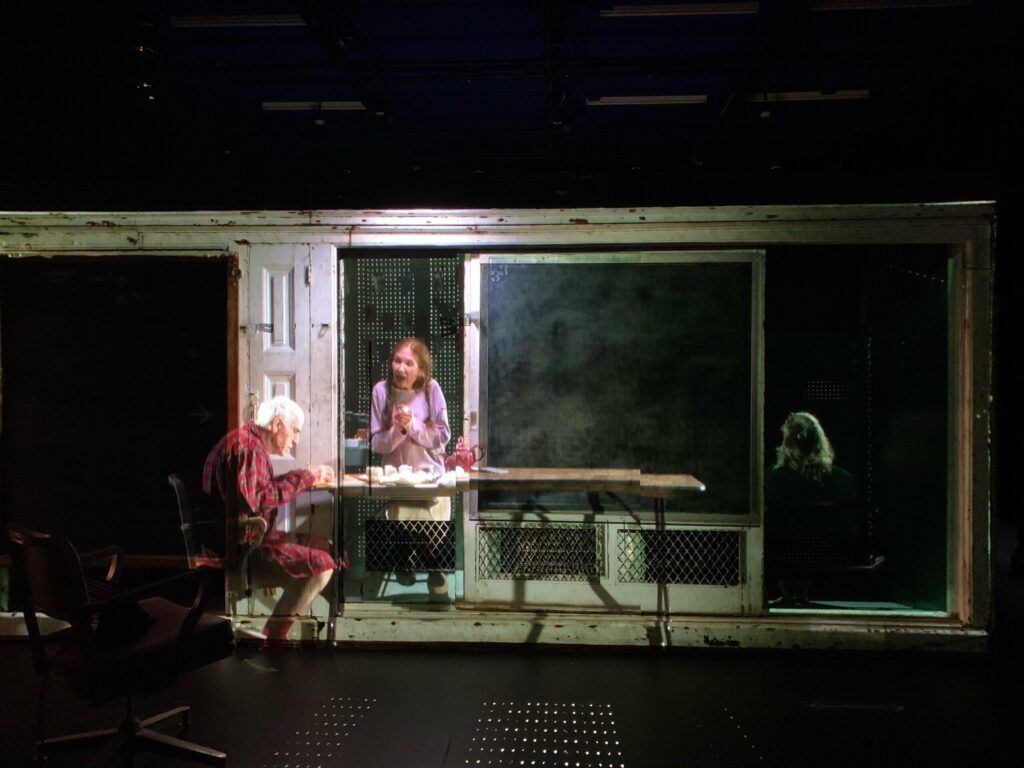

Contrary to the live performance of This Was The End, which featured performers Black-Eyed Susan, Jim Himelsbach, Rae C. Wright, and Paul Zimet, the crowd can walk into and around the set following moving portraits and performances by the same actors from the live play.

Something intangible will draw you to look beyond the physical to the energetic. Finding the balance between contemplation and action, participants are in a position to align the cabinet so that it harmonizes with the tech-enhanced video. By opening and closing the doors, the viewers can read the energy of the physical object expanding their knowledge of the object’s history.

Layering the pre-recorded past onto the actual present structure, Skretch is keen to spotlight the signature aesthetic inherent in the piece:

“In the stage production of This Was The End, we wanted to create an environment haunted by its own history, a kind of emotional echo chamber for the characters. We often talked about it as a memory machine. The actors’ voices looped and cut up live by sound artist G Lucas Crane, their video ghosts captured with them and flashing continuously across the surface of this scenic box—that box itself bringing its own history of course. In Chekhov, there is an undercurrent of characters feeling trapped by their past decisions or indecisions, and this was our way to make that sensation visible, and visceral. Rather than something embodied entirely within the performer, it could be embodied by the whole room, and the performers could play against it.”

An Obie Award-winning theatre director, Catlett developed Archive: This Was The End at CultureHub where she is an associated artist. At once an artifact and an experience where the audience becomes the actor, the exhibition charts the development of a theatrical stage show. In an experiment with form, four characters emerge on video creating a blur of the past and present—producing a pseudoscopic effect—when what is far seems near, and near, far. One can stand where the DJ once stood and watch a video of him mixing the work the audience is experiencing. Door sensors further trigger the work’s play of depth and surface.

Archive: This Was The End. installation at Mabou Mines in New York City’s East Village. Photo By Alexander Fatouros

Outside the salvaged set, a clash of image and space emerges. Inside the inner workings of the piece are revealed.

“Specifically the installation is one part architectural shard or remnant from a building built in 1885. I am not sure when the schoolroom wall/cabinet was installed, but if it was original it was there before Chekhov wrote his first play. It’s fun to think that is possible,” said Catlett.

She continued, adding:

“The other part of the installation is that of the performance and the performers that it archives. Four extraordinary actors over the age of 60, whose roots in the East Village go back at least as far as the 1970s. A legacy that includes Chalrles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company and Joe Chaikin’s Open Theater. That life experience infuses the video portraits and scenes you are witnessing now in 2021. Working with them over such a stretch of time (12 years) connects me to that time in some mysterious way that is hard to put words to.”

When it comes to audience engagement, new forms of interactive entertainment inspired by Chekhov’s plays have emerged these days. In his masterworks, Chekhov’s characters express emotion in relation to the landscape that surrounds them. Themes of change are inherent.

Catlett draws a comparison:

“I think as with Chekhov there is stripping away to an essence that comes with big changes. A vulnerability gets revealed. There is loss, always. But through this process, I have gained tremendous insight into my own legacy as a performance maker in New York. I now find myself in a leadership position of a collective of artists with a 50 plus year history. A place that nurtured me and now I am in a position to do that for others. I feel the loss daily of Ruth Maleczech and Lee Breuer. Every time I walk into the building. But there is also a feeling of continuance, persistence, and resilience, which Chekhov writes about too.”

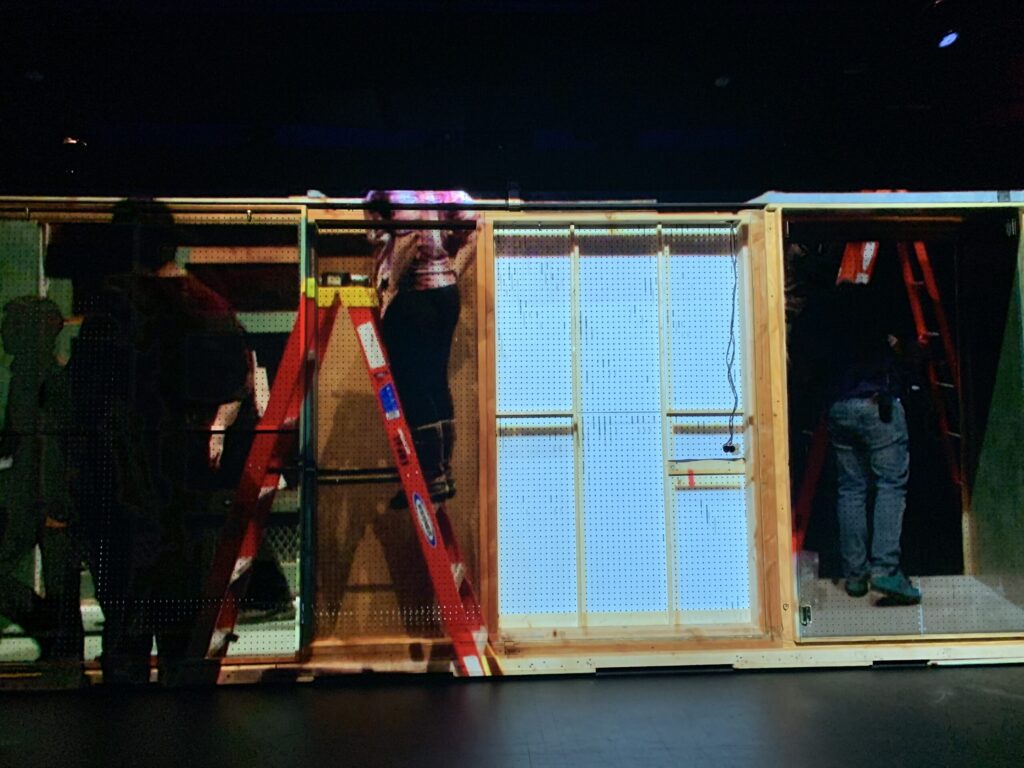

The installation at EMPAC in Troy, NY. Photo Credit: Bill Kennedy.

To create the installation, Skretch and Catlett worked with a 15 member technical team at EMPAC, where the piece was first developed. While the piece examines the afterlife of production, the same actors performed new material, which was filmed from three perspectives. A 2018 The Theatre Times review of the live play revealed:

“…the production is a little too in love with the delightfulness of its own technological possibilities, and the dramaturgy gets buried. The performers, accomplished as they are, get trampled by the tech.”

Ryan Holsopple’s interactive design was bolstered and Peter Ksander’s set was reassembled, which allowed the artists to examine their evolving relationship with technology. Skretch spells out the subject matter of the work:

“The technique itself—projecting imagery back onto the space where it was filmed—isn’t especially novel, but by tying the playback to Lucas’s analog cassette decks it became a little more concrete. Then when paired with this particular surface it created something really uncanny. Because the box isn’t scenery, it’s a literal artifact of a downtown performance space that was excavated from a building, which is now unrecognizable (and in which it is being re-installed). It has its own integrity. The projected image is both ephemeral and kind of clunky. We know it comes from a computer and filters through a digital screen before it encounters us. It’s photographic but not real. But the box is real. So the collision of these two elements is kind of spooky. Not just because the images look ghostly, but because I think it gels with our own lived experience of memory, of existing alongside these people or moments that are long past and yet that stay with us. The images are real ghosts.”

Archive: This Was The End is an animated record and a ruin. Photo By Alexander Fatouros

He continued, adding.

“The installation goes a step further than the stage design by not just conjuring this memory machine, but by removing the supposed subject of these memories, the performers, and inviting the audience to take their place. It becomes less about Chekhov, about these specific emotional feedback loops of Vanya and Sonia and Astrov and Yelena, but about performance more broadly. I think it speaks to the ways we all live within our memories and become haunted by them.”

Archive: This Was The End set is illuminated from all four sides. Photo by Alexander Fatouros

“Of course we first assembled all of this way before Covid, but now like everything else to do with liveness and presence it’s been refocused by the pandemic. So what originally felt like an experiment in taking the performers out of a performance isn’t just a sort of hypothetical invitation. We all now know what it feels like to have a show without performers, or a performance without an audience. Absence itself has become tangible to us in a way. And it’s terrifying but also a new kind of safety. That membrane of absence became our circle of protection. And in a way that’s maybe the truest form of the piece, just a box in the middle of a dark room where it used to live, a shell within a shell, covered by the dancing shadows of an action that once took place there, which just keep repeating and repeating, a little bit differently each time, until the power goes out,” said Skretch.

A glimpse inside the inner workings of Archive: This Wast The End. Photo Credit: Keith Skretch

Through the blending of timelines, the piece converges as a record of performance, Catlett comments on the installation’s significance:

“The installation records the passage of time, change over time because the video that is mapped onto the wall is a recording of all of our pasts, that is continually projected onto the structure itself which is material and present. Change over time is what the work shows in visceral detail.”

She continued, adding:

“The significance is that the piece is an act of preservation. It’s why I do what I do—an attempt to make something ephemeral and precarious palpable. The fragility and the vitality of aging—in bodies, objects, and buildings—is powerful to me. How do we feel a history in something that we cannot fully know and have not experienced? This work stands for something on the edge of disappearance in many ways. And yet it is very sturdy, full of energy. Children come and play on the swing. That can be a reassurance.”

Attuned to the rhythms of the lighthearted and the serious, Archive: This Was The End is a record and a ruin—a final phase in the life of a performance. As the analog experience presented by Mabou Mines and Restless NYC draws to a close, what does remain constant is the potential for a high level of participation. From the perspective of an art and theatre-loving audience, The Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney ought to consider exhibiting the piece. Tapping new methods to reach audiences, this animated interactive sculpture is a first of its kind—a masterwork worthy of a national tour.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Fatouros.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.