Since their first understated but instantly successful visit to Edinburgh in 2008 with their one-to-one piece A Smile Off Your Face, the Belgian company Ontroerend Goed are always awaited with great anticipation at the festival. In their work, mostly directed by Alexander Devriendt, they’ve explored modern-day romance (Internal), crowd behaviour (Audience),the international stock market (£¥€$), what it means to be a teenager (Once and For All We are Going to Tell You Who We Are so Shut Up and Listen; Teenage Riot), the nature of democracy (Fight Night) and our legacy as a species (World Without Us) – all in individually developed, bespoke formats which served to open up the content in a new way on each occasion. In Fight Night, the audience were given handheld devices to vote for candidates of their choice, in £¥€$/LIES they played with real money, in Internal they were held, kissed, seduced, betrayed and sent handwritten letters at their home address. At the outset of their international career, Ontroerend Goed tapped into the larger trends of participatory, interactive and immersive theatre, but an important feature of their work is that each piece is equally, if not primarily, indebted to continuities within the company’s own oeuvre, artistic growth, and long-standing interests. This interdependence of form and content is possibly nowhere more obvious than in their piece Are We Not Drawn Onward to New Era, originally made in 2014, then revised and remounted in 2018.

Widely advertised as a palindrome in both name and content, this show’s suspense is mostly contained in this formal conceit. The piece opens with the archetypal image of a tree and a slowly evolving biblical image of a couple eating an apple. Then one by one, four other characters arrive, suggesting potential prototypes of a person in charge, a clown, a person of action, a thoughtful youth. Their dialogue, appearing at first as gobbledegook, is intriguing, awkward, grating to the ear; their movements looking as though they are going backward and forwards both at the same time. The image of a man pulling onto the stage the plinth of a fallen statue but looking as though he is simultaneously trying to push it away offers an exciting reminder that we are watching something we might be watching from the other direction too, but we can never envisage quite how this will be done – which keeps us going with it excitedly, despite the awkwardness, despite the struggle to make sense of it all.

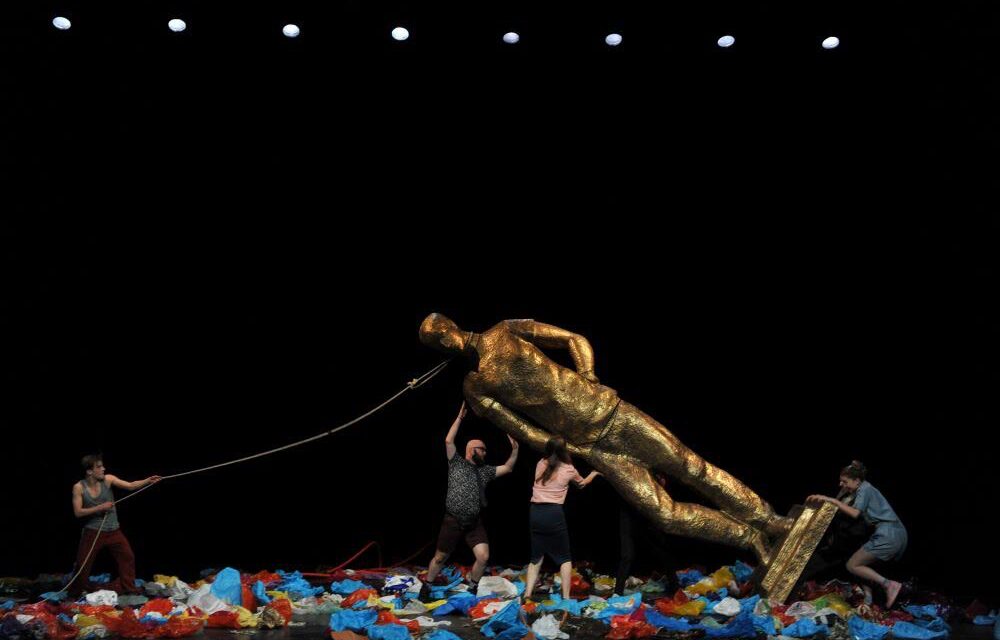

As we reach the mid-point, a tree has been ripped apart, the stage is littered in plastic bags so colorful they look uncomfortably beautiful. Amid this, a gilded giant statue representing an ordinary 21st-century human – jeans, t-shirt, hands tucked in the pockets – is rigged up. Then the theatrical curtain is drawn.

I won’t spoil your own pleasurable suspense by revealing how the second half of the show evolves from this point on but suffice it to say that it is strangely rewarding, often witty and full of wonder.

Ontroerend Goed’s work is sometimes critiqued on the grounds that its focus on form eclipses the urgency of the political considerations of their work. In some ways, this might be seen to be the case with Are We Not Drawn To New Era too. In both directions, however, the show is remarkably busy as it draws attention to the action, labor and, amid that, to the somewhat meta-theatrical dimension of artistic labor and the specificities by which this particular piece of theatre has been made with such meticulous precision. One wonders where the company started from, what came first, how exactly they found the convincing palindromic effect of each detail, the dramaturgical power of each moment… But aside from the formal considerations, the searing significance of the show’s content is inescapable and multiply layered too – what are we doing, where are we going, can we rewind and start over

again, how badly have we messed up, in fact? These questions evoke not only the Bible and Becket but also the very pressing issues of our ecological reality in the 21st century. Formally, there is an apparent sense of wishful thinking, a whiff of a fairy-tale, a formal feelgood factor to the piece, but nonetheless, it is steeped in fragile and deeply conceptual poetry, and those central questions are very much alive and haunting for a long time after you’ve left the theatre.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.