In the past five months, Romanian-born award-winning playwright, poet, and scholar Saviana Stănescu has been in residence at the National Museum of Romanian Literature in Bucharest to work on her new play about the Romanian Revolution. Produced by ARPAS (the Romanian Association for the Promotion of the Performing Arts), The Revolution Project (Proiectul Revoluția) was presented as a staged reading at ARCUB, on October 12, 2019, in the framework of the Bucharest International Theater Platform, and once again on December 16, 2019, a symbolic date which marked thirty years since the beginning of the Romanian Revolution in the city of Timișoara. The cast included Ioana Bugarin, Ioana Flora, Ioana Pavelescu, and Nicholas Cațianis/ Filip A. Condeescu.

D.B: Thank you for the opportunity to discuss this compelling work-in-progress. Tell us about the process of developing The Revolution Project– and the significance of this process for you, as a playwright (and director of the ARCUB production), and for the actors as well. What was it like to translate the American practices of new play development to the Romanian context? How did you arrive at the tripartite – documentary-fictional-documentary – structure of the play?

S.S: As you know, Diana, this past December we celebrated 30 years since the Romanian revolution and the overthrow of dictator Ceaușescu’s totalitarian system. I was born and raised during Ceaușescu’s regime. He was „the father of the people”, as we learned in school. We had his picture on the first page of all textbooks. I grew up in the industrial town of Pitești, with ratios of food and electricity, four hours of hot water per week, and two hours of TV program per day, most of it filled withCeaușescu’s speeches…

In 1989 I was a college student in Bucharest. I wrote poetry but couldn’t publish. My poems were too dark, questioning our daily reality, and didn’t pass the censorship. Each newspaper, theater, literary journal, had censors paid by the government.

There is so much to say here, but I will jump to the Big Change.

Romanian Revolution in December 1989.

I was there, in the University Square, on Dec. 21, 1989, when the revolution started in Bucharest. We literally changed the world – our world. Suddenly we gained unexpected freedom, and I would put the freedom of expression in the first place.

The political censorship was gone and we could finally speak up, shout out our truths.

This past fall 2019 I spent a sabbatical semester (thanks, Ithaca College!) in Bucharest to specifically work on a play that dramatizes the December 1989 events after 30 years – The Revolution Project (Proiectul Revoluția).

I wrote the script from scratch after a workshop with theatre & film actors Ioana Bugarin, Ioana Flora, Ioana Pavelescu and Nicholas Cațianis. We presented a staged reading as part of the Bucharest International Theatre Platform with the theme My Revolution, curated by theatre critic Cristina Modreanu. The National Museum of Romanian Literature, where I am a writer-in-residence this semester, was the co-producer.

You asked me about the process of developing the script. It wasn’t easy to focus on new play development techniques in Romania. The Romanian theatre system is centered on directors proposing projects to state theaters. There isn’t a tradition of national/big theatres commissioning work from playwrights and supporting their new plays’ development.

It helped that our four actors worked in the US or UK previously and had knowledge of the script development process. I directed the staged reading to make sure that I can fully implement my vision as a playwright. Moreover, I took photos of old Bucharest buildings covered in graffiti and created a PowerPoint presentation we used as background for the dramatic scenes. The visual elements made the performance more poignant. I really enjoyed wearing various artistic hats for this particular project. I guess I am a Renaissance woman at heart 😉

In the US, I trust working with a director on new play development because they know how to support the playwright’s vision and inspire the dramatist to make good rewrites that get the play in increasingly better shape.

In Romania there is a strong support for directors to create and stage their own scenarios, but not so much for playwrights to develop new work. “When there are so many great classics to deconstruct in an imaginative way, why bother with a living playwright with a strong vision, who also wants to be a part of the rehearsal process?” Unfortunately, that’s how many established theatre directors think.

However, I must say I collaborated well with a few young directors who staged my plays (Viza de Clown, Organic) in Bucharest, and I am confident that the new generations are reshaping the Romanian theatre culture for the better.

You also asked me about the dramatic structure of The Revolution Project.

Before I came to Romania in August, I did lots of research about Eastern Europe and the end of the Cold War. I read books, e-books, blogs, etc. In Bucharest, I was able to continue my documentation by watching TV statements and debates about that period of time. Plus, as I already mentioned, I actually spent my formative years during Ceaușescu’s regime, and I worked as a journalist in the free press of the 90s.

I strongly value the process of documentation and research.

After the week of workshops with the actors and many hours of thinking about turning dramatic living into dramatic writing, I realized that we can’t have only one narrative about the Revolution, there isn’t such thing. I had to structure the script as a puzzle, a kaleidoscope of perspectives.

I constructed the play in three parts: 1. Documentary Theatre – the actors share (their) personal stories from/about the Revolution; 2. Brechtian – the actors address the audience and become characters; 3. Kilometer Zero, a play based on reality – with fictional characters, some living in Bucharest, others abroad, who share a tragic moment in December 1989.

The new Romanian cinema is quite famous for the hyper-naturalistic movies that portray everyday life and/or reflect on social and political events, but mainstream theatre seems less interested in directly addressing the reality surrounding us.

We know that the Personal is Political, and the Political is Personal. A theatre is a powerful tool for creating social change.

With The Revolution Project I aimed to employ that wonderful tool and give the audiences a glimpse into the playwright’s process of dramatizing recent Romanian history and bringing it on stage.

D.B: You have previously addressed the topic of the Romanian Revolution in Waxing West (La MaMa Theatre, 2007), your first full-length play in English, in the larger context of a tale about immigration, cultural and psychological displacement, the broken promises of the American Dream, and, most importantly, about the myriad ways in which “the ghosts of the past,” dramatized through the uncanny specters of the Ceaușescu dictatorial couple, still haunt and shape the protagonist’s present. As you argued in a previous interview, you only managed to write Waxing West after you moved to the U.S., more than a decade after the event, in your adopted language, English. What made you decide to revisit the topic of the Romanian Revolution in a play fully centered on this historical turning point, and also return to the Romanian language in the process?

S.S: As a playwright, I try to reflect on and respond to the society I live in. The old Brechtian adagio “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it” rings true to me.

In New York – arguably a microcosm of the world – I learned to respect the diversity of backgrounds and perspectives. Immigrants often experience the fear of not belonging, of being THE OTHER – a stranger, a foreigner with a funny accent, an alien who ‘doesn’t deserve’ to be in the US. The American Dream can turn into a nightmare at any given moment. All my American plays explore stories of ‘otherness’, displacement, marginalization, oppression, and resilience. Actually, my Romanian plays too, with a focus on women’s issues. My very first dramatic poem was She-Outcast (Proscrisa), and outcasts have been my favorite characters ever since…

I was very happy when Waxing West – a play written as a graduate student in the “Rita and Burton Goldberg MFA in Dramatic Writing Program” at New York University – went on to win the Golden Award at NYU, get developed in a barebones production at The Lark and fully produced at La MaMa Theatre by Richard Schechner’s East Coast Artists, then win the New York Innovative Theatre Award for Outstanding Full-Length Play.

I felt like I was finally accepted as a playwright in the US. I had found my ‘tribe’.

When I created the characters Ceaușescu and Elena, I was mainly thinking of their dramatic purpose: to pull down Daniela, the protagonist, to remind her of her past, to create obstacles in her struggle to adjust to the new life in the US. I dramatized and theatricalized the in-betweennessthat new immigrants experience, the constant negotiation between the values of the old country and those of the new country. I also wanted to sarcastically engage a few stereotypes about Romania. Which are the first three things/names that come to mind to many US people when they hear the word Romania? From empirical observations, I can tell you: Dracula, Ceaușescu, and Nadia Comăneci…J

When I wrote Waxing West, I was a newcomer in the US, struggling to understand and explore the new society, not unlike the character Daniela. I came to NY with a Fulbright fellowship, not in an arranged marriage, so my situation was clearly better. However, the cultural shock was similar, and my perspective upon my own past and native country progressively changed while assimilating and interrogating the new/local values.

At this point, after living and working in both New York and Ithaca (a small college town upstate NY where I teach) for 18 years, I must confess I feel more American than Romanian… I had to come back and re-immerse myself in the Romanian daily life in order to be able to write a play in Romanian.

I needed the geographical and temporal distance to think about the 1989 events in a new way. And I needed the playwriting craft that I learned in the US to be able to tackle such a complicated, life-altering personal and collective issue.

Nevertheless, it’s funny that now I have an accent in both languages… J

D.B: The reference point in terms of representing the Romanian Revolution on international stages has been Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest (Royal Court Theatre, 1990), developed and produced in the months immediately following the event. How would you position your own perspective in The Revolution Project vis-à-vis Churchill’s rendition?

S.S: Caryl Churchill came to Romania in 1990 with director Mark Wing-Davey and a group of theatre students from London with the goal of creating a play about the Romanian Revolution. I applaud their fast response to history via theatre.

They interviewed Romanians, improvised and workshopped scenes, then Churchill went back to the UK and wrote Mad Forest, which has become the most produced play set in Romania.

It’s essentially a story about two families and a wedding and admittedly does offer a sort of tapestry of complicated local relationships before and after the Revolution.

We also got a vampire and a stray dog in the script, probably as Western stereotypical identifiers for All Things Romania…

As Alex Drace-Francis, professor at School of Slavonic and East-European Studies writes in his essay Sex, Lies and Stereotypes: Romania in British Literature Since 1945:

On the scholarly level, interest in Romania is apparently extremely healthy. On the everyday level, the presentation of Romania in Britain is considerably less consistent. The launch of a new Romanian helicopter may make the news if it is named after Count Dracula; of ten articles treating Romanian politics published in 1996, five featured the former tennis player Ilie Năstase; all three articles on the Romanian economic situation in 1998 concerned the sale of former President Ceaușescu’s possessions in order to raise funds. Orphanages, gypsies, drug-trafficking and murders all get a mention.

Don’t get me wrong, I think Mad Forest is a good and necessary play. I’m a big fan of Caryl Churchill’s work. She inspired me to become a playwright.

But I got a little tired by the fact that Mad Forest gets produced so much in the US, in universities and professional theatres, and people think that this way they diversified their repertory with a play from/about Romania.

You want to do a play from Romania? Produce a play by a Romanian writer. Don’t use Mad Forest as a token for ethnic diversity…

It is true that there aren’t many (if any) Romanian plays about the Revolution. We need to learn from Western European dramatists to artistically respond faster to (our own) history. Otherwise, they get to write our hi/stories again, and again.

As I said, for me, it took many years of geographical distance to be able to write about my life in Romania and the 1989 events. Too many emotions competed with the craft of the playwright – too difficult to write a strong play based on US/UK standards… However, after 30 years and an immigrant experience, I started to feel ready and prepared. I hope to get more institutional support in both the US and Romania, to further develop The Revolution Project into a play that can find its rightful place in American and global theatre.

D.B: Many of your plays dramatize the uneasy relationship between memory and history, with a focus on the intricacies of working through individual and collective trauma. In many ways, The Revolution Project sets out to explore the tension between “the art of forgetfulness” and “the power of memory,” to quote one of the characters in the play. Throughout the show, the latter is poignantly inscribed as a form of justice that might eventually bring about that ever-elusive sense of “closure.” Can you tell us more about the significance of memory as a form of justice and of gaining “closure” in the context of this play?

S.S: These past months I have been a sponge of emotions, watching people telling their personal 1989 stories on TV and reading various confessions in journals. Even former Securitate (Political Police) officers got to share their memories on primetime TV.

I learned that there was a movement inside the Securitate to overthrow the dictator and bring a Gorbachev-like president. Ceaușescu’s political decoy talked casually about his former privileges, then complained about the food he ate during his 52 days in jail after the Revolution. What?! My heart shrunk as I heard testimonies from true political prisoners who got tortured and spent years and years in prison during the totalitarian regime. So many of them…

Memory as a form of justice? Yes, albeit a mild form.

Even now, after 30 years, Romanians don’t have a clear narrative about what really happened at the Revolution. Some people don’t even call it a revolution, but a coup d’état. What is THE Truth – who shot the people protesting in the streets? Was it the Securitate? The Army? The Police? Ceaușescu’s special garde? Foreign “terrorists”? Who?

Dictator Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were judged in a rushed trial and sentenced to death for crimes against the Romanian people. They were executed on Christmas day 1989 as a sort of present – a grotesque “gift” – for the population. The execution was broadcast on the national TV.

How does one write about the Revolution and Ceaușescu – a leader seen as progressive in the 60s when he got the power, and as an abusive paranoid megalomaniac at the end of his regime/life?

There are so many unanswered questions about December 1989 in Romania, but we do have one certitude: over 1000 people died protesting in the streets, shot by we-don’t-know-who, but we do know (most of) their names. I focused The Revolution Project on them, the people who died, many in their 20s or younger. It feels like the right thing to do. To remember them. To plant a seed of justice via theatre and memory… One small step towards making collective and personal traumas stop haunting us in the present. Or so I think.

Working on The Revolution Project helped me achieve a sort of closure and start the healing process. I hope it will help the Romanian spectators too.

D.B: In her seminal study Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater (2005), Jill Dolan discusses the balanced interweaving of discourses typical of documentary plays as creating the conditions for “a conversation among people who might not otherwise have spoken to each other – or not spoken these words in this way – creating a new public sphere in which to scrutinize the events” (p. 113). Not only does The Revolution Projectemerge at the intersection and from the interplay of multiple perspectives and discourses, but its dramaturgical concept also includes a post-show forum section in which the audience members can share their (direct or mediated) experiences of the Revolution and weave their own stories into the layered tapestry of the play. What conversations do you hope to stimulate with this play? What types of audience do you hope to reach and bring together in this collective reflection on the meaning(s) and impact(s) – or, to quote another character in the show, the manifold “realities” – of the Romanian Revolution?

S.S: On December 16, the day the revolution started in Timișoara, we performed the show again at ARCUB (Bucharest Center for Cultural Projects), followed by a Forum in which audience members shared their own stories from December 1989. Many participants weren’t even born at that time, but they spoke about their feelings during the show and the things they learned from TV or their parents. It was very touching to see all of them expressing the need for such plays and events that could heal the collective trauma via theatre, personal stories, and public dialogue.

I generally like to have/moderate talkbacks, especially for the plays that employ documentary theatre devices. However, in all my plays I tackle social issues that need to be further discussed with the audiences.

In the US, we had several panel discussions after Dream Acts(co-written with Chiori Miyagawa, Mia Chung, Jessica Litwak, and Andrea Thome), Aliens with Extraordinary Skills, Hurt, Ants, For a Barbarian Woman, Bechnya, Lenin’s Shoe, The Others, Bee Trapped Inside the Window, Gun Hill,Back to Ithaca – A Contemporary Odyssey, YokastaS Redux(co-written with Richard Schechner, from whom I learned collaborative theatre practices), etc. The talk-backs were very useful for all of us, artists and audiences, as they deepened topics, expanded conversations and bridged gaps between the artistic sphere and the public one.

The notion of closure is not fully understood by most Romanians. Psychological and mental health issues are still stigmatized and avoided in discussions. How can you start to heal if the problem is not acknowledged?

The Revolution Project is not meant to replace therapy of course, but I created a character, Bianca, who speaks about the need for closure and hopefully gets people to understand better the term and start to be at ease with it. And we offer the post-show Forum as a safe and brave space to talk, share, and begin to heal.

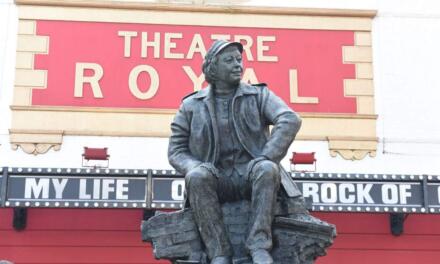

The staged reading of The Revolution Project. Photo by Lavinia Cioaca

I hope to reach Romanian, American, and international audiences that are inquisitive, thoughtful, and interested in truthfully exploring the similarities and differences of our societies and communities. I am curious to see in future Forums how spectators of various ethnic/racial backgrounds see memory as a form of justice and history as a ground zero for learning…

D.B: One of the four stories in the second part of the play is centered on Radu, a character who participated in the Revolution and later decided to immigrate to Spain, and who is also part of the LGBTQ+ community. What were the stakes of representing this particular story on the Romanian stage at this particular moment?

S.S: As recent as two years ago, there was a national referendum for defining marriage in the Romanian constitution as a union between a man and a woman…

Luckily, it didn’t pass, but still. In Romania, gay people have often been persecuted and marginalized for being who they are. During the totalitarian system, many would be arrested, blackmailed, forced to commit suicide, etc.

I am glad that women’s issues, LGBTQ+ perspectives, racial discrimination, were among the topics examined in The Revolution Project and discussed during the Forum, as such matters are still rather ignored on Romanian stages.

For the December 16 performance, Filip A. Condeescu came from New York to play the role of Radu, a former political prisoner (arrested many times for being gay) who now has a peaceful life abroad, shared with a nice husband and a little daughter. At the post-show Forum, Filip talked about his own struggles as a gay man in Romania, before immigrating to the US.

Ioana Flora is an actress raised in Serbia, known from many Romanian movies including The Christmas Present– shortlisted this year for The Oscars. She resumed her role as Bianca, a Romanian-American science-fiction novelist haunted by a secret from the past. Ioana Pavelescu had the tragic experience of being pregnant at the Revolution and losing her child. She imbued her character, Casandra, with realness, and even found the power to use humor in performance. Ioana Bugarin, an up-and-coming star of Romanian theatre and film, gave a new life to Ana, a mysterious young woman who makes graffiti on buildings in Bucharest, Madrid, New York, and brings the others together. But I shouldn’t reveal the plot, maybe you get to see the play somewhere in the world…

Oh, you might think that all talented actresses are named Ioana in Romania. It’s just a beautiful coincidence, and I totally used it in the Brechtian part of the script 😉

D.B: What are your plans and hopes for the future of this show? Do you plan on bringing it to American audiences as well? If so, how do you envisage a translation (in the broader sense of cultural translation) of the play for the American context?

S.S: Our goal is to present the play again in Bucharest, then abroad, for the Romanian diaspora and foreign audiences. Totalitarian systems, oppressed communities, revolutions, im/migration, are topics that many people can relate too across the globe. We all hope to learn from each other’s histories/herstories/theirstories and continue our search for truth. Or so I imagine…

However, I think I would need to slightly rewrite the play for American audiences. The references and aesthetic expectations are different in the US – a solid story and fleshed out characters are somewhat mandatory.

In Europe postmodern/postdramatic theatre is already old news, but in the US it hasn’t arrived in the mainstream yet.

It’s funny that in the Romanian version of The Revolution Project, I aimed to emphasize the construction/development of story and characters, while in the American version I will try to maintain some of the postdramatic and absurdist elements. Well, cultural translation has never been easy…

Luckily, I can write plays in both Romanian and English now.

A big shout-out to all translators out there and to the US theatres that produce international plays! In the current global climate, with nationalism rising in many countries, working/thinking across borders is a must.

Let’s be curious, open, understanding, vital, and not limit ourselves to immersing into only one culture. It’s not healthy. It’s lonely. It’s retrograde. It’s dangerous.

BIO: Dr. Diana Benea is an Assistant Professor in the American Studies Program at the University of Bucharest, Romania, and a former Fulbright Senior Scholar at CUNY – The Graduate Center (2017-2018). Her current research focuses on the theory, praxis, and pedagogy of theatre for social change, with a focus on documentary and community-based formats.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Diana Benea.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.