Based on a recent phone interview with Al-Zaidi, the most prominent Iraqi playwright.

Ali Al-Zaidi is the most celebrated playwright in contemporary Iraqi theatre. His plays have been translated into English, French, Spanish, Turkish, Farsi and Kurdish, and they have been produced throughout the Arab world. Al-Zaidi’s plays, mostly dark comedies, dramatize the consequences of wars, hunger, and oppression, in which the predicament of his characters is ridiculed and the absurdity of their existence within their war-ridden country (Iraq) is highlighted.

Al-Zaidi has emerged, finally, from beneath the shadow of war, hunger and dictatorship. He was born in Nasiriya in 1965, and his hometown has been a haven for his body and soul through a lifetime of suffering and loss beginning early in life: his father died when he was a child and his older brother was killed in the Iraq-Iran war.

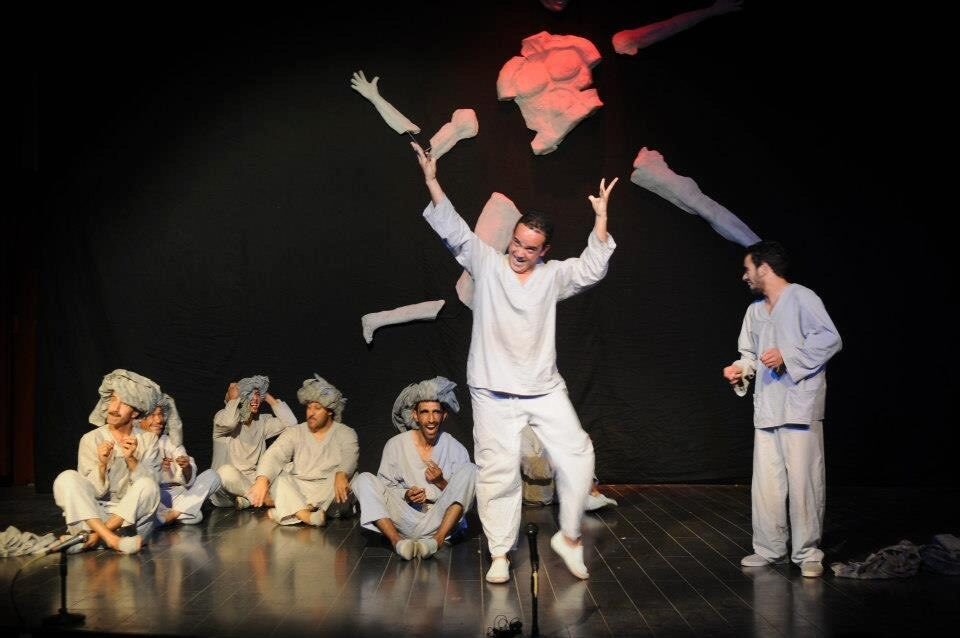

Safinat Adam (Adam’s ship), National Theatre, Baghdad, 2015.

In 1984, he started writing for theatre, looking for a style that distinguished him from other Iraqi and Arab playwrights. Al-Zaidi began as an actor and author in his play Niqtat Bidaya (a start point). He was influenced by the Theatre of the Absurd: “My characters allow me to enter into their irrational world, a place where thoughts, dreams, desires, and aspirations are no longer pursued.” Theatre of the Absurd has been the dominating dramatic style in Iraq since the 1980s; it has been exhausted by playwrights as they attempt to depict the uncertainty and meaninglessness of the situation in their country.

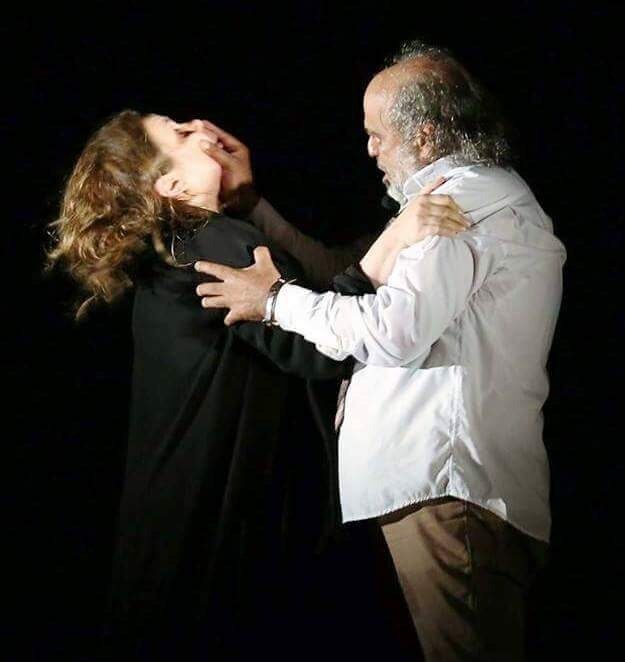

Mayit Mat (A corpse has died), Masrah al-Nashat al-Madrasi, Nasiriya, 2020.

The core question for Al-Zaidi is: “Why are we here?” This question is rendered into a constant existential anguish: born without seeking birth and die without seeking death, trapped unknowingly in our body and mind. “I don’t know why I feel like I’m going to die soon. This obsession that has been haunting me and making me not to care so much about this life”, he added. Although his statement sounds pessimistic, Al-Zaidi believes in life through his characters. For him, death compels him to create those characters so they can live after he leaves. However, Al-Zaidi’s plays don’t fully adhere to the absurdist conventions such as incoherent dialogues, lack of plots, or incomprehensible characters. Nonetheless, Al-Zaidi’s plays search for a lost identity and meaning for metamorphized characters stuck in hypothetical time and place that is characterized by waiting, fear, anticipation, depression, anxiety, tension and frustration.

Ya Rab! (O Lord!), National Theatre, Baghdad, 2016.

Commenting about his plays, characterized as grotesque by many theatre critics, Al-Zaidi postulates that his relationship with life is “sometimes sarcastic and sometimes indignant”, and that he “ridicules everything in order to formulate it again through the act of irony…I turn taboos and sacred things into profane … make the unexpected completely expected despite the impossibility of its occurrence…”. Al-Zaidi’s discontent with life, power, and dictatorships is interpreted as protest in his theatre, especially plays exploring the legacy of wars and repressive regimes. Al-Zaidi believes that as long as oppression and violation are flourishing, the Iraqi absurdity is and will be prevalent.

Haqa’ib Barida (Untraveled Suitcases), National Theatre of Lattakia, 2018.

Photos are provided by the playwright

Selected plays collections:

Thamin Ayam al-Usbu’(the eighth day of the week) 2001, The General House of Cultural Affairs, Baghdad.

Awdat al-Rajul alathi lam Yaghib (Return of the man who wasn’t absent) 2005, Arab Writers Union, Damascus.

‘Aradh bil Arabi (a show in Arabic) 2011, The General House of Cultural Affairs, Baghdad.

Comedia al-Ayam al-Sab’a (comedy of the seven days) – translated into Farsi, 2015.

Al-Ilahiyat (the divine) 2014, Dar Tammuz, Damascus.

Maba’d al-Ilahiyat (the post divine) 2017, Dar Amal al-Jadid, Damascus.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Amir Al-Azraki.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.